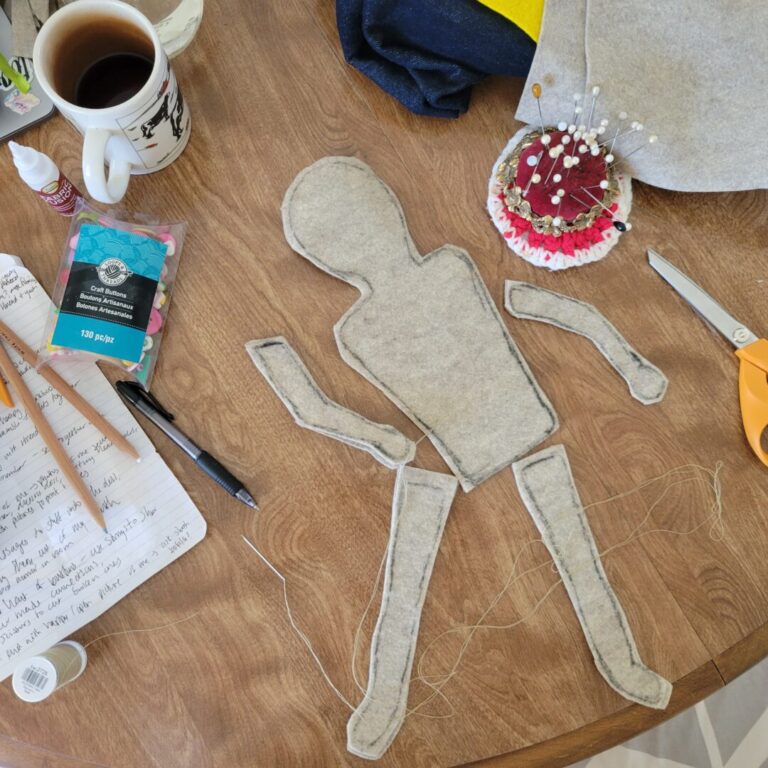

During the Spring semester 2020, I took an art class at the Rhode Island School of Design. “Personal Protective Purple Daikon Equipment: A Handbook” was my final project for the class. Part zine, part Zoom performance experiment, part autistic meltdown, the project bears witness to my anger, isolation and fear during the lockdown. It is both a commentary on academia and the constant demand to “make use” of every experience—to continue academic life as usual even during a pandemic that saw so many disabled people die—as well as a handbook for making one’s own Personal Protective Purple Daikon Equipment (PPPDE) at home and an absurdist manifesto. As a research-creation project, the Personal Protective Purple Daikon Equipment offers a snapshot of a moment in (crip) time, that of the first state-sanctioned lockdown and of the early days of the pandemic.

Special Sections

Special sections published within or across issues.

How Do You Grieve During an Apocalypse?

This essay is a rumination on loss during the pandemic—not only the physical loss of loved ones but the loss of experiences and time. Focusing specifically on the death of my aunt, Joyce Dana Apostole, I reflect on what it means to mourn, not only as an individual but as a collective. Through the retelling of significant moments in Joyce’s life and recalling our relationship, I consider the questions: How do you navigate grief when you cannot congregate with others? How is that grief compounded by institutional failures—medical, governmental—and informational lack? And how does social response to individual and mass loss reflect philosophies and policies that (continue to) devalue—and prove detrimental to—the lives of disabled people? Ultimately, this essay is not only a reflection on grief, but it is also a eulogy, an opportunity to fully recognize my aunt and her complex history, a life shaped by illness and disability in ways that counter popular narratives of recovery and overcoming. It is an archive of not only what was, but what wasn’t, necessary documentation within a culture in which “return to normalcy” can become synonymous with forgetting.

On Navigating Paranoia, Repair, and Ambivalence as Crip Pandemic Affects, Or, I’m So Paranoid, I Think Your COVID Test Is About Me

How do my “hermeneutics of suspicion” color this current crisis? In this auto-theoretical essay, I reflect upon the blend of judgment, suspicion, and paranoia that have settled into my body-mind this past year, and how these feelings shape my engagement with people, institutions, and systems. I have been taught that “judgment” is an essential aspect of immigrant and crip safety. Recently, it has become my (crip)epistemology, and I cannot decide whether this is for better or worse. On the one hand, suspicion is productive. It has kept me and my loved ones alive in a time of deliberate death. On the other, it frustrates, disrupting my capacity for connection. I check my temperature constantly, I hear the guilt in my voice when my family in India tell me they have not left the apartment in months, I spend precious time with friends calculating their risk relative to mine, I go to protests but am afraid of the consequences of my solidarity. Drawing on Eve Sedgwick’s essay on paranoid reading practices, Patricia Stuelke’s Ruse of Repair, Sianne Ngai’s work on ugly feelings, Nikolas Rose’s analyses of somatic ethics, and Mel Chen’s theory of racialized toxins, I explore the modalities that paranoia has both enabled and disabled for me. I examine my ambivalent relationship with repair—some reparative practices like mutual aid sustain queer/crip/immigrant community while others like cure constrict our lives. This piece aims to tease out the tensions latent in crip worldmaking between suspicion and generosity, public health and communal care, and paranoia and repair.

The Queer Aut of Failure: Cripistemic Openings for Postgraduate Life

I, a Mad, autistic, multiply-disabled person, began my PhD in Cultural Studies in September of 2020. I started to make my home in graduate school during the COVID-19 pandemic, fully online, and I’ve excelled, calling into question normative assumptions of in-person socialization, education, and collaboration as superior to their virtual counterparts. In this article, I reflect on the cripistemic pedagogies of failure that facilitated a neuroqueered and transMaddened transition to Zoom-based graduate life. I will also consider email, text messages, and video calls as equalizing mediums in which both formal and fugitive spaces can open for queercrip collaboration across borders, timezones, and access needs. Lastly, I will tell the stories of technological “failures” that I have experienced—miscommunications, failing internet, time delays—as generative possibilities rather than indictments of a non-normative learning. Necessarily imperfect and rife with humorous, intriguing, and profoundly human failures, as well as surprising and generative openings, pandemic education has ushered in new queercrip, transMad, ways of knowing and teaching that have uniquely benefitted me. Far from a circumscribed or lacking educational landscape, I argue, post-COVID academia is filled with pedagogical and epistemological openings, holes through which new disabled and Mad scholars, myself included, can make ourselves a beautifully imperfect home space. I invite you inside.

Roundtable: Crip Student Solidarity in the COVID-19 Pandemic

This roundtable shares the first-hand experiences of five crip, disabled, Mad, and/or neurodivergent doctoral students navigating academia in so-called Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. While we discuss and theorize our experiences of ableism, structural oppression, and inaccessibility in the academy, we also highlight the world-building experiences of solidarity that have emerged for us in crip community, and in particular among fellow crip graduate students. We consider the ways that crip students open up potential for new ways of learning and being by challenging dominant norms of academic productivity, and we also consider what is lost when these students are pushed out of academic spaces. By engaging in “collective refusal” of the conditions that harm disabled and otherwise marginalized students, new possibilities emerge for connection, community, and radical change. The virtual conversation transcribed here took place over Discord, email, and Google Docs in autumn of 2021 and early winter 2022. This piece embraces multi-tonality, that is, a range of different voices and ways of writing, speaking, and communicating. It is a conversational piece that intentionally blends varied approaches to knowledge-sharing: polemic, citationally-grounded, and personal anecdotes drawn from our diverse lived experiences. There are a number of different themes woven throughout the text, including anecdotes and personal history, solidarity, ableism in the academy, pessimism/failure, community/interdependence/intimacy, and utopia/futurity/demands for the future. While not intended to provide policy guidance or step-by-step instructions for changing academic culture, we also begin to sketch out some of our dreams for an alternative future for disabled scholars. We discuss imagined futures and possibilities, and ask, is a truly crip and/or accessible academic institution possible?

Our Thoughts: Reflections on OCD, the Pandemic, and Society

In this socially engaged and collaborative project, the topic of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is explored artistically. A poem and sculpture depict and contemplate the lived experience of OCD and how it relates to contemporary times. The project grew out of a friendship between Mick, the alias for someone who has OCD, and Dana Fennell, a researcher who studies OCD.

Chronic Illness Wisdom is Both/And

This poem reflects on dual tensions that sick & disabled communities have to navigate during ongoing pandemic conditions. In particular, it addresses the chronic illness knowledges that people with post-viral illnesses already possess (the reality of chronic conditions after acute infections, the necessity of solidarity across bed space) in the face of medical and political institutions that refuse to know.

August 2020

Unemployed at the time, not visibly disabled, but having become quite unwell in the middle of a pandemic, this poem illustrates my anxious and exhausting insomnia against the caretaking labor for my youngest child. I worked to minimize the projections of stress and anxiety onto her, laboring for stillness and comfort. As Luce Irigaray states in An Ethics of Sexual Difference (1993), “Music comes before meaning. A sort of preliminary to meaning, coming after warmth, moisture, softness, kinesthesia” (168).

Overwhelmed

The isolation, stress, and uncertainty fueled by the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged our collective mental health. For people with preexisting psychiatric disabilities, these repercussions are further magnified. This is particularly true for individuals who have experienced involuntary confinement in “corrective” facilities. For survivors of institutional abuse, the gross restriction of movement generated by the quarantine and lockdowns replicates the systems of total control to which they have previously been subjected. Facing an uncertain future and lacking access to community support systems, many survivors have been forced to improvise mechanisms to relieve traumatic symptoms on their own. While these self-soothing mechanisms can provide relief during moments of acute distress, they may be ultimately destructive and exacerbate long-term symptomatology. This artwork is an expression of overwhelm and the conundrum faced when survival strategies that meet immediate needs threaten long-term well-being.

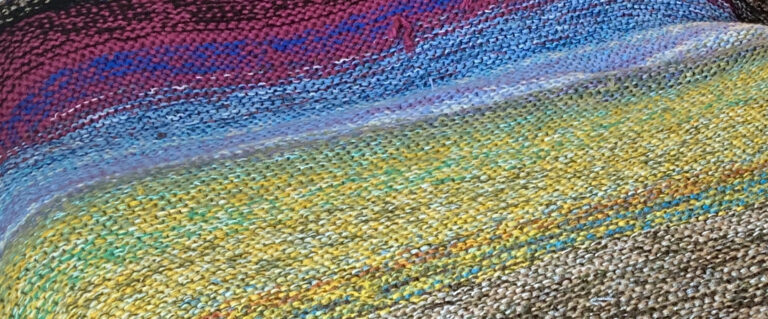

Security Blanket: Neuroqueer Knitting in Pandemic Times

This article presents neuroqueer knitting as a cripistemological practice in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which the author realized that knitting was part of how they moved through trauma. Tracing the process of making a blanket during part of the pandemic, a time in which they were also relocating, the author argues that knitting offers a knowledge-making practice aligned with their autistic ways of being in the world. Treating this blanket as theoretical material, the author uses it to challenge ableist ideas of autistic people as lacking the capacity to narrate their experiences. Instead, this blanket is used to reflect alternative modes of knowing that document the author’s continued existence and survival in moments of trauma and upheaval.

assembly required: textures of madness, joy, memory

This piece stitches and layers together a mix of photographs, poetry, and reflections to tell a story—my story—of c-PTSD, grief, (chosen) family, and my constant yearning to exist fully as myself.

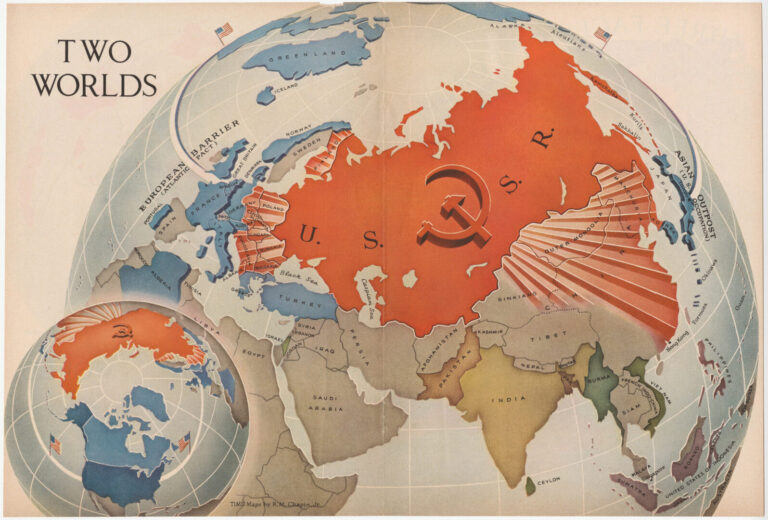

2013—East by Eastwest: Cultural Studies’ Route to Eastern Europe

In Eastern Europe, which is the focus of our study, different national scholarly traditions assigned their own place to the study of culture. Although the influence of the kulturologia (“culturology”) schools installed at Russian universities in the 1980s radiated out into Eastern European countries, local academic communities dictated the approach to the study of popular culture. While the Polish field of kulturoznawstwo was propelled by internal forces from the early 1970s onwards, in Czechoslovakia, kulturologie emerged as a new discipline around the fall of the Communist regime. Even so, it failed to take off and by 2012 had vanished completely from the Czech Republic. Central European countries were also affected by the German academic tradition of Kulturwissenschaften with its emphasis on philosophy and aesthetics. Our inquiry highlights the first international conference on cultural studies in the Czech Republic in 2013. It was during this event that a group of new postdocs from Charles University, including ourselves, raised the topic of changes in Eastern European popular culture due to the political transformation in 1989. This group had also arranged for Ann Gray, the final director of the UK Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) to give a keynote address at the conference, a gesture that clearly linked the CCCS with the group’s own Centre for the Study of Popular Culture (CSPK) established three years earlier. From the outset, CSPK’s organizers aimed to promote the Anglo-American tradition of cultural studies both in the academy and among the general public. At the same time, they sought to retain their independence from academic structures and funding systems that might restrict their political activism.

Introduction: Cripistemologies of Crisis: Emergent Knowledges for the Present

The increasing recognition of critical disability studies as a generative body of work across disciplines is inseparable from a collective need to make sense of ongoing moments of socio-political crisis, emergency, and exceptionality. Theorizations of crip time emergent from lived experiences of disability are critical to the ongoing work of understanding and surviving a chronically debilitating socio-political context. Our current political moment seems to protract states of crisis to such a degree that the very notions of emergency and crisis shift under the weight of their simultaneous seeming banality and urgent ubiquity. “Cripistemologies of Crisis: Emergent Knowledges for the Present” contends that epistemologies of chronicity, illness, and trauma offer indispensable lenses through which to rethink—and care for—our collective present. The essays within “Cripistemologies of Crisis” reframe our understandings of both social and personal crisis, and explore how crisis and emergency shape the experiences and knowledges of our bodyminds in time and space. The authors collectively offer an epistemological toolkit to theorize and survive everyday states of trauma, madness, and illness as the lived impacts of such quotidian and ongoing violence. “Cripistemologies of Crisis” asks, then, what crip futures can be conjured through a centering of experiential, collective, and speculative ways of knowing with/in/through crisis.

When Silence Said Everything: Reconceptualizing Trauma through Critical Disability Studies

Reading X González’s, March 24, 2018, “March For Our Lives” speech—their words and silences—as an entry point into what I term a crip theory of trauma, this essay argues that the dominant narratives about and around Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) say more about the compulsivity of the “proper” citizen subject than they do the actual embodied experience and debilitation of trauma itself. The text reconceptualizes trauma narratives, like González’s, through critical disability studies to argue that certain cripistemologies—or crip ways of knowing—trauma arise that are not otherwise available or readily accessible. Most notably, by rejecting dominant pathologizing forces and embracing crip ways of knowing, this analysis brings forth a new working definition of trauma, as an embodied, affective structure. These ways of knowing offer crucial insights for efforts to grapple with the ongoing forms of trauma enacted and perpetuated across the globe, and are particularly urgent against a political and cultural landscape that, as my reading of González’s speech makes clear, in many ways refuses to hear, see, and learn from the knowledge that trauma produces.

Solidarity in Falling Apart: Toward a Crip, Collectivist, and Justice-Seeking Theory of Feminine Fracture

In this essay, I reconceptualize feminized trauma by utilizing a queer crip feminist disability justice framework. This reconceptualizing allows for an intervention in both historical psychoanalytic and contemporary biomedical framings of the experience of gendered and sexual violence, pursuant or sequelic trauma, and associated symptoms. Both historical and contemporary psycho-logics too often imagine gendered and sexual violence as abnormal or exceptional events (e.g., “stranger rape”) which can be treated and cured individually, thus delimiting them within a white, wealthy or middle-class, cis- and hetero-feminine register. As a corrective, within the framework of everyday emergencies, insidious traumas, and cripistemologies of crisis, I position feminine fracturing and falling apart as chronic, and consider abolitionist strategies for survival, care, and solidarity beyond traditional medical frameworks for recovery. This further provides a way to understand dissociation or rather dissociative-adjacent symptomology as real, legitimate, and painful, yet also as sociopolitical products experienced differently across diverse populations—and as mundane, banal, and even expected for some. Here, feminine fracturing is symptom, method, and potential avenue for change or liberation. What does “recovery” look like when feminized trauma is endemic to the point of being so normalized and unexceptional as to be a thoroughly unremarkable part of our everyday cultural backdrop? How is this exacerbated when we examine the experiences of trans women, poor women, and immigrant and BIPOC women and femmes? I posit that there is promise in embracing a fracturing, in falling apart—as antidote to the normative and neoliberal logic of keeping it together.