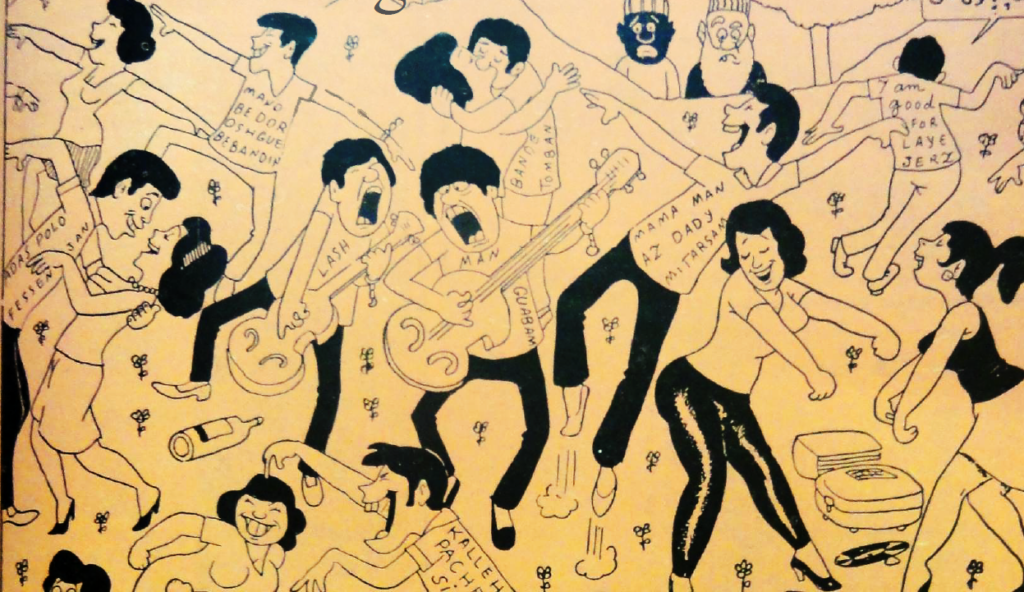

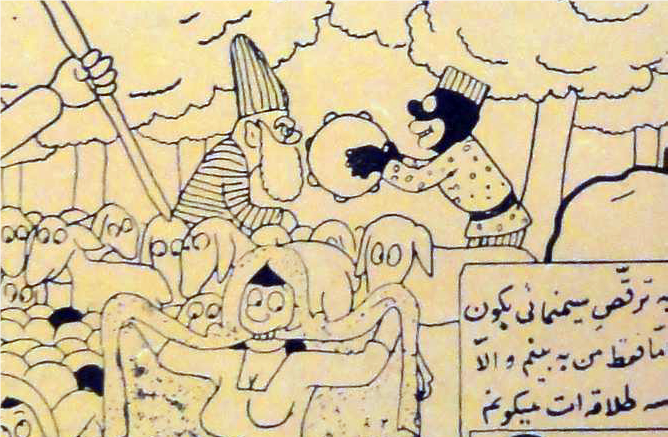

In a brief, unexceptional comic strip published in the Iranian magazine Sipīd ū Sīyāh (white and black) on the occasion of the final day of the 1965 Persian New Year, four half-page cartoon images framed by simple square panels overlay discrepant temporalities and caricatured modes of New Year festivity. Above or below each panel, short captions correlate the images with imaginary social spheres: “the fukuls‘ New Year” (sīzdah bidar-jhīgūlhā [fukulī-hā]), “the provincials’ New Year” (sīzdah bidar-i umulhā), “the tough guys’ New Year” (sīzdah bidar -i jāhilhā), “the opium addicts’ New Year” (sīzdah bidar -i ham shīr-i hā [taryākīhā]). Fukul, from the French “faux col” is a derogatory term for someone infatuated with the West as well as a blanket Persian term for youth 1950s subculture.1 The fukuls panel appears first in the sequence and contains just one balloon of Persian script. Instead, aggressively absurd all caps pinglish phrases are scrawled across dancing youths’ polo tee-shirts. As with the other panels, the cartoonist captures the mobile fukulīs in mid-dance. The tilted hips, arched backs, and gestural hand outlines of the female figures in the “tough guys” and “provincials” squares indicate vague Eastern styles of dance (one kneeling man in the “provincials” cartoon orders his wife to “dance like they do in the cinema but just for me”). By contrast, the fukuls move with elongated limbs simulating movements suggestive of nondescript mid-century Western-style pop dancing (figure 1).

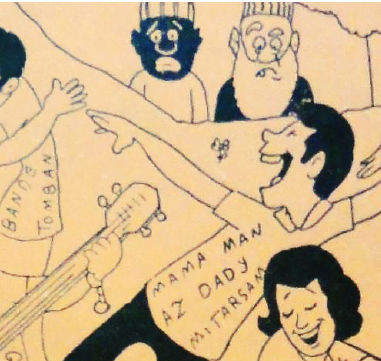

Apart from the falsely celebratory, deeply sinister ethos and univocal chromatic scheme, the consistent element connecting the panels across gutters is Hājī Fīrūz and Amū Nowrūz, a pair of icons associated with the Persian New Year—one in blackface, the other white. In the “provincials” and “tough guys” panels, Hājī Fīrūz shakes his tambourine and dances enthusiastically with Amū Nowrūz, dissolving into the plane of action, while in the fukuls frame, the pair’s concerned faces peer over the jagged horizon of a mountainscape that folds depth of field (figure 2). Hājī Fīrūz’s enlarged white lips curl downward in a frown, while Amū Nowrūz raises one brow over his bulging eye sockets, forming the only moment of reflexivity—therefore, of interruption— in the series.

An enigmatically global phenomenon, blackface practices are rarely studied in comparative contexts. Where they are, scholarship often assumes a modern North American origin, or argues for its worldwide spread as effects of colonialism and imperialism.2 By contrast, the insularity of the Persian narrative regarding traditional figures like Hājī Fīrūz and the blackface protagonist of the improvisatory sīyāh bāzī (black play) tradition oscillates between unsophisticated historicism and wild speculation. By virtue of its form, the 1965 comic strip offers a more dynamic approach to interpreting the history of Persian blackface, suggesting an intrinsic relationship between comic form (exemplified by the comic strip) and blackface.

The stock types identified by the Sipīd ū Sīyāh comic (fukul, umul, jāhil, and indeed, Hājī Fīrūz) are ubiquitous clichés in one of the most important contemporaneous cultural forms of 1960s Iran: fīlmfārsī, a generally disparaging term for Iranian commercial films of the period. Despite the impending dissolution of traditional figures like Hājī Fīrūz and Amū Nowrūz that the 1965 comic communicates, Hājī Fīrūz and sīyāh bāzī (the larger improvisatory tradition of which he forms a part) flourished within the Pahlavi-era cinematic mode of fīlmfārsī. Sīyāh bāzī’s transition from a centuries-old tradition of improvisatory street theater to film, television, and published periodicals like Sipīd ū Sīyāh and Tawfīgh conjures a peculiar transmedial force to this indigenous blackface tradition. I suggest that, in part because of their roots in caricature, the comic strip form shares with both the Persian improvisatory tradition of sīyāh bāzī and the commercial phenomenon of fīlmfārsī an essence to the transmediality of blackface comedy that reflects its meaning as racial. This connection between comics and the racial revolves around the reduction of human complexity intrinsic to the process and functioning of both comic form and of racialization.3 We might call this reduction thaumaturgic, alluding to the strange “alchemy” in which simplification conditions conceptualization, identification and “closure” in the process of comic meaning making.4

Generally held in disrepute by the Iranian middle classes and the scholars who tend to represent and reproduce their interests and investments in respectability, fīlmfārsī, like the obscure comics found in Pahlavi-era reader digest genre magazines such as Sipīd ū Sīyāh, has rarely formed an object of sustained inquiry. Where it has, scholars have focused on the reproduction of more obviously culturally relevant stock figures like the jāhil (tough guy, or thug) represented by the Sipīd ū Sīyāh comic, a postwar fantasy form of warrior masculinity comparable to the idealized lūtī, ayār, and javānmard common to Persian literary and visual culture. (Rūstam and other epic heroes of Firdawsī’s Shahnamah are its prototype.) Traditional forms of masculinity were revamped and revitalized by famous fīlmfārsī stars like Behrūz Vūsūghi in Ghaysar.5 Or, scholars have concentrated on the omnipresent dancing female body, also foregrounded in the Sipīd ū Sīyāh strip when it is evoked by a man’s demand to his wife to do a private “cinema dance” (taraqus-i sīnamāyī bukun).6 Recent scholarship agrees upon a certain incongruity between the Pahlavi nationalist project and the fīlmfārsī genre. Fīlmfārsī reflects neither the political preoccupations of national unification and ethnic homogenization, nor the opposing views of radicalized Shi’i inspired politics, but a kind of alternate technological venue for fantasies of the good life channeled through American-style consumerism and collective desire.7

If blackface persists in fīlmfārsī, then, it is unlikely due to a simplistic synchronic correspondence with the racial dislocative nationalism of the time period.8 Rather, this persistence must be comprehended through a more complex kind of temporal configuration that is suggested by the comic form. Sīyāh bāzī shares no simple analogy in other forms of ethnic denigration because, first and foremost, blackface is a global, rather than uniquely Iranian phenomenon—unlike the anti-Arab sentiment that theorists of nationalism isolate as the most characteristic form of modern Iranian racism. (Blackness, lacking a robust, or systematized repertoire of iconography in Western Asia, gets subsumed into Arabness wherever the Arab is conceived as a racial other; in Turkish, for example, “Arap” can be a derogatory term for Black people. And yet, the language and framework of anti-Arabness fails to account for why Arabs have their own repertoire of denigrating iconography for Blackness.) Thus, rarely have analyses of “race” in the Iranian context been pursued from a point of view that could be called Black, that is, informed by a consciousness surrounding the global history of Blackness.9

The perception of sīyāh bāzī’s history is clouded by the fact that improvisatory traditions, like myth and ritual, naturally lack systemic textual traces or scripts.10 Though scholars generally agree that documentary evidence for sīyāh bāzī appears only in the Safavid period (around the sixteenth century), they also suggest a much deeper, probably pre-Islamic genealogy dovetailing with nowrūz-bāzī (New Year festivities) to which Hājī Fīrūz and other traditions like asb chūbī, and kūsah bar nishīnī belong.11 In the absence of documentary certainty, obscure and ideologically-driven genealogies are not difficult to craft; in the case of Hājī Fīrūz, a shifty origin reaching back to Sumerian mourning rituals supply Iranian nationalists with a uniquely Persian defense of the blackface tradition that purifies its history and conveniently disavows, to this day, its contamination with histories of African slavery and anti-Black racism.12

A genre of taghlīd (literally, imitation), sīyāh bāzī emerges out of a comedic form analogous to mime, and its historical practitioners, like the mimes of antiquity, played a crucial role in shaping political communication between the populace and court in the absence of contemporary media circuitry and apparatuses.13 Sipīd ū Sīyāh hardly exemplifies the politically subversive potential of sīyāh bāzī in its 1965 comic strip, all the more understandable since Hājī Fīrūz, though arguably an iteration of sīyāh bāzī, generally lacks the latter’s embedding into story plotlines and potential for political bite. Nevertheless, an imprecisely satiric, if conservative pathos coalesces through the visual commentary of the sequential imagery, affirming sīyāh bāzī’s inherent, if degraded politicism. This politicism—like his mythical origins— is usually, and myopically, claimed by commentators of the tradition to mark an exceptionalism that defends against accusations of racist caricature.14

In the Sipīd ū Sīyāh weekly, Hājī Fīrūz bears witness to the simultaneous antagonistic temporalities embodied by modernity. Like a bleeding panel,15 his sad, interruptive gaze in the first image drags through and portends the doom suggested by the latent misery in subsequent scenes. Hājī Fīrūz’s iconicity, therefore, is not merely mimetic, for it underlies the entire structure of the comic form, even in the taryākī-hā (opium addicts) frame from which he is notably absent. Drawing upon the involvement of early American animators in vaudeville entertainment, Nicholas Sammond has identified blackface minstrelsy as the origin and creative source of the animation industry more broadly.16 In the Sipīd ū Sīyāh comic, sīyāh bāzī characteristics vitalize even the areas of the image apparently unconcerned with blackface. Solecistic thought balloons mimic the mutilated speech of sīyāh bāzī, where the sīyāh, incapable of pronouncing proper Persian sentences, replaces consonants like shin with se and lam with re.17 In the comic, slurred words indicate drunkenness, and grammatical inversions affirm the backwardness of the “provincials”—infiltrating space with the malapropic effects of sīyāh bāzī, and of Hājī Fīrūz (who is otherwise silent in the cartoon).

It is not surprising that Hājī Fīrūz should spread sīyāh bāzī blackface elements to areas of the comic unconcerned with Blackness. Unlike film, television, and other time-based media, the comic form spatializes and gathers time in one place; it is a visual medium capable of holding together multiple elements—temporalized by the gutter, or gap between panels—on a single page. In this sense, the comic strip form is peculiarly qualified to represent the temporal disjunctiveness of Iranian modernity that the cartoon flagrantly mocks, as well as the peculiarly abiding force of a Blackness that not only keeps watch over this disjunctiveness, but symbolizes, reflects upon disjunction itself.

If each panel represents a distinct, internally differentiated temporality, the first panel signals the mood or mode through which they should be read. But Hājī Fīrūz’s concerned gaze does more than set a mood. Simplification, the condition of possibility for the cartoon image—and of entry into the conceptual—is doubled, strengthened in this strip by Hājī Fīrūz’s blackface, that is, by a cartoon representation of a cartoon representation of Blackness. In other words, there is an enigmatic dimension to the 1965 comic embedded into the very practice of blackface that the comic’s sīyāh bāzī content represents. This enigmatic dimension is an expression of the cartoon essence of the human subject motored in the panels by the automated movement of non-choreographed dance. It comes through perhaps most inauspiciously in the addicts’ panel, where the oblivious figures hang lifelessly on strings handled by a puppeteer who charges “one shahi” for each shake, revealing the edges of a distinction between the animate and inanimate that Blackness reduces, absorbs, and hyperbolizes.

Iranian critics contemporaneous with the commercial mode of fīlmfārsī generally agreed with Western film theory about the worthless cliché trafficking exemplified by the stock characters of fīlmfārsī who are represented by the comic.18 Critics as contextually disparate as Amīrhūshang Kāvūsī and Gilles Deleuze concede that rather than enrich and inspire, clichés stunt and seal our perceptual capacity.19 Indeed this disdain of the cliché traces back to antiquity; Plato famously derided theater, but especially, improvisatory theater for its capacity to reproduce that “fretful part of us” prone to imitation and theft.20 It is precisely this vulnerability of the human subject available to reduction, repetition, re-animation, and therefore to a revelation of inauthenticity and self-difference that the blackface of sīyāh bāzī holds and wields as a thaumaturgic force underlying the comic. The sīyāh is the mark of comedy, and not merely an aberration of the genre or one among other versions of it.

The placement of dancing Hājī Fīrūz in the panels representing folk strata of society (the tough guys and the provincials) suggests his naturalized relation to traditional Iranian culture, whereas his reflexive placement in the fukuls panel, where he regards the jiving fukulīs alongside Amū Nowrūz with dismay, suggests Hājī Fīrūz’s incongruity with and impending extinction in the modern. The panel thus roots sīyāh bāzī in the immemorial time of tradition, and suggests its disappearance, rather than birth, in modernity, reversing the usual chronology and trajectory of influence framed by stories of blackface transnationalism. But the point that is made in placing Hājī Fīrūz in the sole position of reflexivity is even more complex. Just as the fīlmfārsī stereotypes are not pure representations of traditional roles, but uniquely modern mediations (the postwar jāhil model of masculinity is a case in point), the global apparition of blackface minstrelsy can only be partially understood with the tools provided by historicism, diachrony, chronology. What the comic suggests is that Hājī Fīrūz, and the blackface tradition that he represents, become legible as such, through a disruptive encounter, in whose wake sīyāh bāzī is neither placeable as traditional nor modern, ancient or new: it is made into a problem contemporaneous with the emergence of such distinctions. Rather than a prosaic, staged encounter between tradition and modernity, then, we can read the 1965 comic as a relation between (innocent, uncontaminated, traditional) sīyāh bāzī and the racialized blackface minstrelsy represented by the fukuls who champion Western modernity. On such a reading, sīyāh bāzī’s meaning would no longer lie simply in the past nor in the present, in its purportedly pure Persian origins nor in a supposedly contaminated form, but somewhere suspended in relation to a future signaled by Hājī Fīrūz’s sequential placement on the horizon. There sīyāh bāzī awaits not its extinction, but the ever deferred arrival of its authenticity and truth.

From the standpoint of the comic’s audience, there is no “good” frame in the comic strip; each box evokes a morally undesirable position and degraded social class. The umuls are hypocrites: the wife dancing cinematically lifts her chador over her breasts to reveal a low cut dress; a manager reprimands his servant for adding oil from his own company brand in the family’s food; veiled women are juxtaposed with sheep (figure 5). The jāhils are illiterate; the fukuls are spoiled and oblivious. In this context, wholesome Hājī Fīrūz and Amū Nowrūz appear as the wisest, least degraded characters of the group. Yet unlike the other stock types, who, even in the cliché-saturated fīlmfārsī mode appear with greater nuance than expressed by the comic, caricature is the dominant, even sole mode through which Blackness ever appears in Iranian cultural forms. The hegemony of caricatural or cartoon Blackness suggests less that the cartoon is itself a racial medium or formation, than that racial Blackness can only ever be expressed through the simplifying gesture at the origin of the cartoon. This is the primary point that defenders of blackface practices, when connecting it to nonracial origins and prehistory, misunderstand. As scholars of visuality and Black representation troublingly show, the gesture that strips physical reality down to its bare anthropomorphic elements is the same gesture that renders Blackness visible as racial (it is the same, implicitly reprehensible, and dangerous, model of perception that colorblind rhetoricians imagine they avoid by claiming they “do not see” race.)21

Notes

- The popularization of the Persianized “fūkūlī” from the French word for false collar (faux col) is sometimes attributed to Jalāl al-i Ahmad’s 1962 Gharbzadigī, or Westrickenness. Reprint, Qum: Nashr-i Khurram, AH 1390 {2011 CE}. ↩

- Catherine M. Cole, “American Ghetto Parties and Ghanaian Concert Parties: A Transnational Perspective on Blackface,” in Burnt Cork: Traditions and Legacies of Blackface Minstrelsy, edited by Stephen Johnson (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), 224. Some scholarship connects American minstrelsy to early modern European contexts (George F. Rehin, “Harlequin Jim Crow: Continuity and Convergence in Blackface Clowning,” Journal of Popular Culture 9, no. 3 (1975): 682–701; Robert Hornback, Racism and Early Blackface Comic Traditions (Springer International Publishing, 2018); Virginia Mason Vaughan, Performing Blackness on English Stages: 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). ↩

- What is the racial? What is racialization? We do not arrive at satisfactory answers by consulting textbook definitions, which are hopelessly mired in contradiction. For example, Robert Miles, one of the first sociologists to historicize the term argues that racialization “alludes to the historical emergence of the idea of ‘race.’” Robert Miles and Malcolm Brown, Racism (London: Routledge, 2003), 102. However, what one means by “historical emergence” shifts depending upon one’s orientation toward the meaning and genealogy of the concept of race. For my purposes here, I understand the “racial” as originally rooted in the reduction of human complexity to hierarchized differences based upon real or imagined characteristics, parts—like perceived skin color— that stand in for wholes. ↩

- On closure as a form of alchemy, see Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (Northhampton: Kitchen Sink Press, 1993), 73. ↩

- For a relatively recent study of fīlmfārsī, see Pedram Partovi, Popular Iranian Cinema Before the Revolution: Family and Nation in FīlmFārsī (New York: Routledge, 2017). Minoo Moallem suggests that the circulation of this type of masculinity via traditions such as naghali, contributed to the formation of revolutionary subjectivities. Minoo Moallem, Between Warrior Brother and Veiled Sister: Islamic Fundamentalism and the Politics of Patriarchy in Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015). Hamid Naficy translates the jāhil as “thug” and suggests his correlation with modern, post-World War II forms of masculinity. Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 266 ↩

- Ida Meftahi, Gender and Dance in Modern Iran: Biopolitics on Stage (New York: Routledge, 2016). The ubiquitous female dancer is a phenomenon paralleled in Egyptian cinema and attests to the infiltration of Egyptian melodrama prior to Iran and Egypt’s political tension after the 1952 revolution. ↩

- Partovi, Popular Iranian Cinema, 16. Rather than an accessory of Pahlavi nationalism, Golbarg Rekabtalaei similarly identifies fīlmfārsī as a site of contestation to the modernity imposed by top-down nationalism. Golbarg Rekabtalaei, Iran Cosmopolitanism: A Cinematic History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 186.) ↩

- On dislocative nationalism, see Reza Zia-Ebrahimi, The Emergence of Iranian Nationalism: Race and the Politics of Dislocation (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016). ↩

- A case in point is Neda Maghbouleh’s The Limits Of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race (Stanford University Press, 2017), which, symptomatically, includes virtually no analysis of anti-Blackness, despite the North American geographical context within which the study is situated. ↩

- Muhammad Bāqir Anṣārī, Namāyish-i Rūhawzī: Zamīnah va ‘Anāṣir-i khandah’sāz (Tihrān: Shirkat-i Intishārat-i Sūrah-Mihr, 2008), 44. Ya’qūb Āzhand, Namāyishnāmah’nivīsī dar Īrān, az Āghāz tā 1320 (Tihrān: Nashr-i Nay, 1993), 15. Bahrām Bāyzāī, Namāyish dar Īran (Tihrān: Intishārāt-i Rawshangarān va Muṭālaʻāt-i Zanān, 2000), 47. Mahmūd Ṣābirī Khūrzūqī, Namayish-i Kumidī Dar Īrān (Tihrān: Āfarīnah, 1999), 29. Like Willem Floor, Mahmoud Haery suggests taghlīd (the larger genre of improvisatory theater of which sīyāh bāzī constitutes one form) originates prior to Islam, only to be reanimated in the Safavid period, while Ghafārī admits sīyāh bāzī’s “date of appearance is unknown.” Willem Floor, The History of Theater in Iran (Washington, D.C: Mage Publishers, 2005), 200; Mahmoud Haery, “Ru-howzi: The Iranian Traditional Improvisatory Theatre,” (PhD diss., New York University, 1982), 20; Farukh Ghafārī, “Evolution of Rituals and Theater in Iran.” Iranian Studies 17, no.4 (1984): 372. ↩

- On various Nowruz traditions such as asb chubi and kūsah bar nishīni, see Hashem Razī, Jashnhā’yi Āb: Nawrūz Savābiq-i Tarikhī ta Imrūz Jashnhā-yi Tīrgān va Āb-Pashan (Tehran: Intishārāt- i Bihjat, 2004). Commentators generally collapse the difference between the sīyah figure of sīyāh bāzī and Hājī Fīrūz, suggesting Hājī Fīrūz is a “stock type” of taghlīd (Floor, History of Theater in Iran, 49) though for a divergence of opinions about the relation between taghlīd and Nowrūz-bazi, see Ardashīr Sālih’pūr, Girāmāfūn va Namāyish: Tārikh-i Tahlīlī-i Taghlīd va mazhakah dar Īrān (Tihrān: Namāyish, 2011), 66). For a suggestion that Hājī Fīrūz is itself a relic of a tradition separate from Nowruz, see Razī, Jashnhā’yi Āb, 202–12. ↩

- The linguist Mihrdad Bahār’s pseudoscientific theory about Hājī Fīrūz’s origins in the festival of Dumuzi fuels nationalists’ rejections of Hājī Fīrūz’s racist depiction in countless online forums about Hājī Fīrūz. Mihrdād Bahār, Justārī dar farhang-i Īrān (Tihrān: Ustūrih, 2007). ↩

- Anṣārī, Namāyish-i Rūhowzi, 43; Husayn Nūrbakhsh, Dalqak’hā-yi mashhūr-darbārī va maskharah’hā-yi dawrah’gard az zamānha-yi dūr tā avākhir-i ‘ahd-i Qājār (Tihrān: Kitābkhānah-i Sanāʼī, 1976), 47. For the political significance of mimes in antiquity, see Szakolczai Arpad, Comedy and the Public Sphere: The Rebirth of Theatre as Comedy and the Genealogy of the Modern Public Arena (New York: Routledge, 2012). ↩

- As I argue elsewhere, this exceptionalism is belied by the fact that all global iterations of blackface minstrelsy have been conceived of as political forms. ↩

- Bleeding panels refer to panels that bleed off the page, suspending any certainty about the image’s temporality. ↩

- Nicholas Sammond, Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of Animation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015). ↩

- Bihrūz Gharībpūr, Ti’ātr dar Īrān (Tihrān: Daftar-i Pizhūhishhā-yi Farhangī, 2005), 53. ↩

- Amīrhūshang Kāvūsī, a leading cultural critic, was first to coin the derogatory term filmfarsi, but as Parvīz Jāhid points out, critics of the 1950s and 60s almost unanimously saw filmfarsi as “hollow, vain, indecent, vulgar, and worthless.” Parvīz Jāhid, Directory of World Cinema: Iran (Bristol: Intellect, 2012), 67. ↩

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema II: The Time-Image, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989). ↩

- Samuel Weber, Theatricality as Medium (New York: Fordham University Press, 2004), 38–39. ↩

- For the problem of Black representation, see for example, Nichole Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2011). ↩