Following the cataclysmic AIDS epidemic in the 1990s, a defiant embrace of the word “queer” and new technology sparked an influx of films by independent filmmakers that were later termed “New Queer Cinema.” As a product of its time, New Queer Cinema interrogates the heteronormativity it conflicts with and thus breeds a reimagining of what queer film can look like. The conflict between queer identity and its heteronormative surroundings drives distance between queer individuals and their communities, as well as larger social structures. This distance leads to a sense of isolation. This article explores themes of isolation within select New Queer Cinema films and offers a potential reference point from which we can understand queer life and cultural production in the midst of yet another global illness—COVID-19. Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (1991) highlights isolation from heteronormative social structures, particularly the nuclear family unit. Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996) focuses on a curation of queer kinship as a survival tactic in the face of this isolation. Gregg Araki’s Totally Fucked Up (1993) and Thomas Bezucha’s Big Eden (2000) both explore themes of self-imposed isolation. Totally Fucked Up provides an essential New Queer Cinema perspective of this phenomenon; meanwhile, Big Eden challenges assumptions that queer individuals are destined to be isolated by imagining a future in which this is not the case. Themes of isolation are essential to the New Queer Cinema genre as a product of its circumstances. Yet, it also provides a basis from which the possibilities of future queer cinema and culture can be imagined. Understanding this relationship is critical as we begin to understand the effects of structural and social isolation on the queer community as exacerbated by COVID-19.

Keyword: cinema

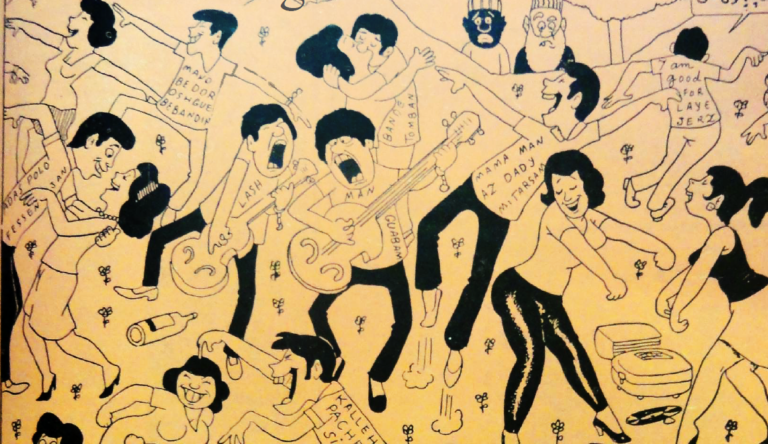

Thaumaturgic, Cartoon Blackface

This essay explores how a particular medium—the comic—exposes the limitations of conventional narratives about sīyāh bāzī (Persian blackface) and hājī fīrūz (a famous blackface figure). Many commentators disavow the racial connotations of sīyāh bāzī and hājī fīrūz, concocting pseudo-historical genealogies that link the improvisatory tradition and figure to pre-Islamic practices; commentators thus repress the tradition’s obvious resonances with the history of African enslavement in Iran. Through a close reading of a comic strip from a 1960s Persian periodical, I argue that historicism is an inadequate framework for adjudicating sīyāh bāzī’s racial or “nonracial” character. Instead, I suggest that cartoon Blackness is always already racial, since the comic form depends upon a process of simplification that is at the heart of racialization.

Political Blackness, British Cinema, and the Queer Politics of Memory

This essay queries “political Blackness” as a coalitional antiracist politics in England in the 1970s and 1980s. Contemporary debates on the relevance of political Blackness in contemporary British race politics often forget significant critiques of the concept articulated by feminist and queer scholars, activists and cultural producers. Through close readings of Isaac Julien and Maureen Blackwood’s The Passion of Remembrance and Hanif Kureishi’s Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, this essay examines cinematic engagements with political Blackness by foregrounding the gender and sexual fault lines through which queers and feminists articulated relational solidarities attentive to difference.