Tehrangeles Dreaming is the first book about the Tehrangeles music industry, that is, the Iranian diaspora music industry brought to life by the expatriate Iranian artists and music producers who settled in Los Angeles and Southern California after the 1979 Iranian revolution. Farzaneh Hemmasi uses an ethnographic approach in combination with an analysis of diaspora media discourse in order to “examine expatriate imaginations of influence on, and intimacy with, their global Iranian audiences” (26). At its core, the book deals with the imagining and reimagining of Iranian identity by the artistic community that creates music and media content for Iranians in Iran and across the world.

Keyword: Iran

The Myths of Haji Firuz: The Racist Contours of the Iranian Minstrel

Every year, around the arrival of the Spring equinox, Iranians in Iran and in diaspora will recognize a minstrel named Haji Firuz with his Nowruz jingle. The inclusion of Haji Firuz during Nowruz festivities has been questioned and challenged for decades; where some will point out his connections to anti-Blackness, others will defend Haji Firuz, arguing that his face is only covered in soot from fires also associated with the holiday. This article contextualizes these arguments as a part of a larger discourse of denying racism in Iran and, more poignantly, erasing Iran’s history of slavery altogether. This article addresses the consequences and pitfalls of defending Haji Firuz’s blackface performance, and its implications for the broader Iranian community.

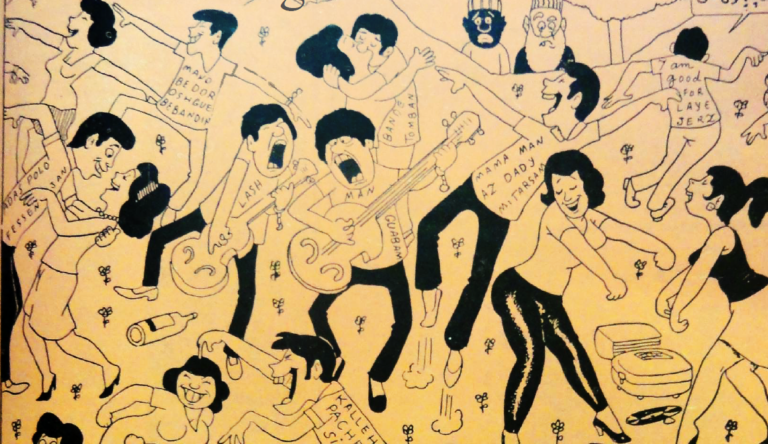

Thaumaturgic, Cartoon Blackface

This essay explores how a particular medium—the comic—exposes the limitations of conventional narratives about sīyāh bāzī (Persian blackface) and hājī fīrūz (a famous blackface figure). Many commentators disavow the racial connotations of sīyāh bāzī and hājī fīrūz, concocting pseudo-historical genealogies that link the improvisatory tradition and figure to pre-Islamic practices; commentators thus repress the tradition’s obvious resonances with the history of African enslavement in Iran. Through a close reading of a comic strip from a 1960s Persian periodical, I argue that historicism is an inadequate framework for adjudicating sīyāh bāzī’s racial or “nonracial” character. Instead, I suggest that cartoon Blackness is always already racial, since the comic form depends upon a process of simplification that is at the heart of racialization.

Troubling the Home/Land in Showtime’s Homeland: The Ghost of 1979 and the Haunting Presence of Iran in the American Imaginary

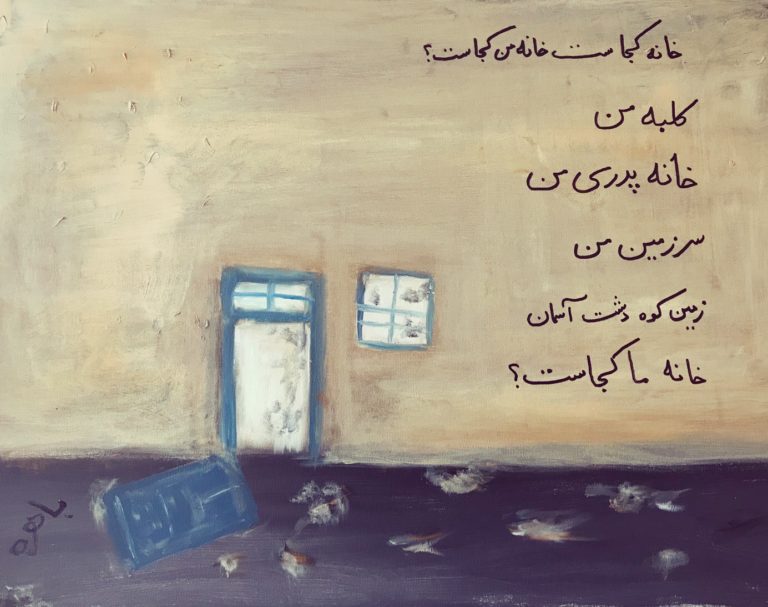

In my close reading of the drama series Homeland, I illustrate how the divisive pull between “fascination and contempt, desire and disgust” as well as the “simultaneous embracing and disavowal” that cultural critics argue define Iranian Americanness become embodied in the character Fara, a young Muslim Iranian American woman recruited into the CIA for her language and technical skills. This essay asks, among other questions: what does it mean to have anxiety over your birthplace or ancestral homeland? What does a “simultaneous embracing and disavowal” do to a person over time? I argue that as a consequence of how her body is read, Fara is continually denied access to a home and a land and ultimately becomes discarded after performing her role as an agent of the state apparatus. In addition, this essay considers how the ghost of the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979 is frequently invited to speak as an origins myth for contact between the US and Iran that subsequently shapes the lived realities of Iranian Americans nearly forty years later.