In a well-known formulation, Vijay Prashad wrote that, “The Third World was not a place. It was a project.” This forum feels out ways to understand and remember the Third World project as a collective horizon of freedom enacted by ordinary people in their daily lives. Beyond the political leadership of the iconic leadership of Third World state leaders and the foundational conferences they convened, we seek to explore how the Third World was lived and imagined. We do so as an invitation to fellow teachers and students to deepen collective imagining through a twin process of learning and unlearning. Formulated as a practice of Third Worlding, this invitation is a proposal to make historical precedents familiar and make progressive visions of intersectional, anti-racist, decolonial struggle strange. It seeks out other ways of calling comrades into political practices by exploring the ways in which Third World subjects imagined and related to each other. In this introduction, we lay out what Third Worlding might offer as a tool for reorientation in the political present.

Keyword: media

Hearing the Houma: Sound, Vision, and Urban Space in Moroccan Hip-Hop Videos

This paper seeks to engage the construction of urban “soundscapes” as a potential flashpoint for class conflict by analyzing auditory and visual representations of “the neighborhood” (al-houma) in a handful of Moroccan hip-hop videos. I begin by situating Moroccan hip-hop within transnationally circulating associations of hip-hop with “urban” life, as well as the political dynamics of North Africa’s colonial and postcolonial urban histories. I then analyze four videos comparatively, suggesting that each goes beyond lyrical and musical content of the songs to construct a sensory experience of the city—or neighborhood—for the listener-viewer. In giving attention to the political implications of each video, however, I argue that what distinguishes each is less what sort of “soundscape” emerges in his video but how each video teaches the audience to “hear” the Houma. While videos by mainstream rappers Muslim and Don Bigg figure urban space as threatening and in need of moral recuperation, they enact these pedagogies largely through indexical figurations of their respective soundscapes, that is, by directing the listener to attend to certain (inaudible) sounds and to interpret them in a certain way. By contrast, a video by El Haqed, known as a more staunchly oppositional figure, visually and sonically constructs a peri-urban lifeworld conditioned by neoliberal economic abandonment yet resistant to the postcolonial gaze. This contrast, I suggest, raises crucial questions about how hip-hop is linked to broader dynamics of cultural appropriation and “resistance” politics.

For the Moment, I Am Not Scrolling

Andrew Culp and Cultural Studies Association’s New Media and Digital Cultures Working Group Co-Chair Claudia Skinner take a look into Adi Kuntzman and Esperanza Miyake’s new book Paradoxes of Digital Disengagement: In Search of the Opt-Out Button, published by University of Westminster Press (2022).

Review of Spectacle and Diversity: Transnational Media and Global Culture by Lee Artz (Routledge)

Lee Artz’s Spectacle and Diversity: Transnational Media and Global Culture brings to our attention the ways transnational media has created representations of global culture. By analyzing examples of nations with transnational media networks he acknowledges how each nation’s media culture has become a reflection of transnational ideals. Artz critiques the transnational ideals that benefit elites and the careful fusing of the themes such as self-interest, social mobility, and individual successes into media to maintain the status quo. The book concludes with a plea for a non-capitalist international movement to bring forth a new media wave, which might benefit the interests of humanity.

Review of Media and the Affective Life of Slavery by Allison Page (University of Minnesota Press)

In Media and the Affective Life of Slavery, Allison Page interrogates how media culture from the 1960s to the present has mobilized the legacy of slavery for affective governance, or “the production and management of affect and emotion to align with governing rationalities” (6). Throughout the book, Page’s analysis succeeds in providing a rich mapping of the converging interests of state actors, media producers, educational organizations, and other stakeholders as they narrate their own desire to manage emotions in the wake of the civil rights movement and to maintain white supremacist order.

Review of The Gentrification of the Internet: How to Reclaim Our Digital Freedom by Jessa Lingel (University of California Press)

What could we discover about the forces shaping the internet, and what could we learn about how to fight back against those forces if we committed to the metaphor of gentrification? In The Gentrification of the Internet: How to Reclaim Our Digital Freedom, Jessa Lingel shows that gentrification can be a useful lens through which to expose how power and class play out in online space. In a moment of increasing techno-skepticism, The Gentrification of the Internet offers a starting point for action, grounded in the reality of urban gentrification activism with proven results.

Review of Television and the Afghan Culture Wars Brought to You by Foreigners, Warlords, and Activists by Wazhmah Osman (University of Illinois Press)

This review examines Wazhmah Osman’s book Television and the Afghan Culture Wars, an ethnographic study of television media in Afghanistan. The book explores the Afghan mediascape through richly detailed interviews with media industry professionals and local Afghans, which provide a realist portrayal of the perils and triumphs of media houses in Afghanistan, local cultural contestations, changing gender norms, and the role and reception of television in the nation’s rather tumultuous political and cultural life. Osman deflates the dominant notion in Western discourses of Afghanistan as a “hopeless landscape of powerless people,” (2) arguing that there is a thriving, internationally backed media infrastructure and a hopeful, culturally conscious citizenry in the nation. She argues that despite Afghanistan’s history of violence, ethnic tensions, atrocities against women, and imperialistic agendas by foreign powers, the Afghan media sector is a widely accessible platform for retribution against years of underdevelopment and war, with “the potential to underwrite democracy, national integration, and peace” (3).

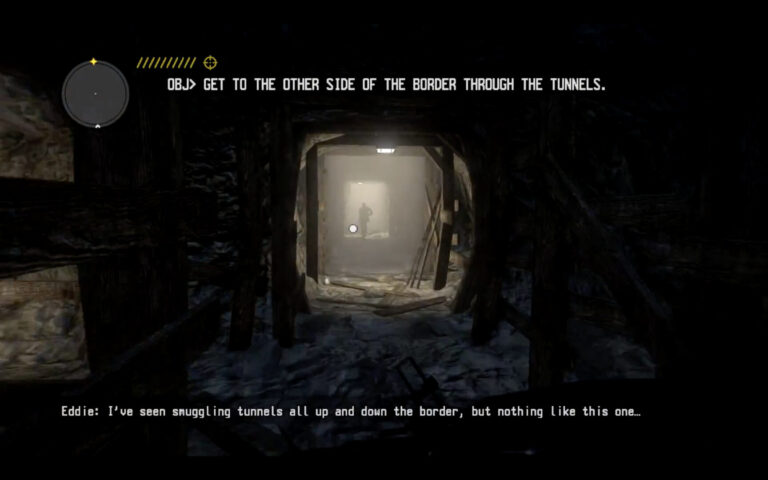

First-Person Shooters, Tunnel Warfare, and the Racial Infrastructures of the US–Mexico Border

Digital networked media actively participate in the nation-state’s and tech entrepreneurs’ efforts to imagine and manage the borderlands. These media facilitate virtual forms of thinking about the border both by offering popular reference points for the new technology being developed (e.g. Google Maps, Pokémon Go, Call of Duty) and by providing the actual tools through which these ideas can become actionable. This article analyzes one such reference point within the first-person shooter (FPS) console game Call of Juarez: The Cartel (Ubisoft, 2011). Like other border-themed video games, The Cartel borrows on colonial tropes and ideologies by creating playable narratives that invoke the untamable frontier and position racialized subjects as Other. Through its virtual modes of representation and interaction, the game encodes the racialization processes that continue to shape popular imaginings of the border. While its digital aesthetics animate a dynamic space of possibility, the logic of the first-person shooter reins in the expansiveness of animated space by restricting it to an interactive experience of tunnel warfare, an ideological orientation to the border underground that channels the players’ purposive motion into a space of direct confrontation and racial violence. Analyzing the narrative and procedural work of this ostensibly reactionary video game demonstrates how border infrastructures structure and shape specific forms of racial and colonial violence.

Review of Media Hoaxing: The Yes Men and Utopian Politics by Ian Reilly (Lexington Books)

The review evaluates Ian Reilly’s analysis of Yes Men hoaxes as a means of calling attention to corporate greed and abuses of power as well as a new mode of political engagement that entails from utopian dispositions the reformist aspirations to nudge society towards a better version of itself. It emphasizes the innovative approach for of The Yes Men to “sharpening a political critique” and coupling it with doing politics differently. It highlights Reilly’s findings of the dependency of hoaxes’ success on contextual factors and encourages future studies to capitalize on Reilly’s work to develop an account of the “ecosystem” in which media hoaxes circulate.

Review of Talking White Trash: Mediated Representations and Lived Experiences of White-Working Class People by Tasha R. Dunn (Routledge)

In Talking White Trash, Tasha R. Dunn provides a multi-methodological investigation into the representations of white working-class people on screen and the everyday lives of members of the white working-class. Her work provides a nuanced way to understand the reinforcement of stereotypical depictions of this population, as well as how the white working class “talks back” to these representations. The book draws from the current political and cultural moment to assert how white working-class identity is constructed, and advocates for a more complex reading of this population than is often provided in mediated texts.

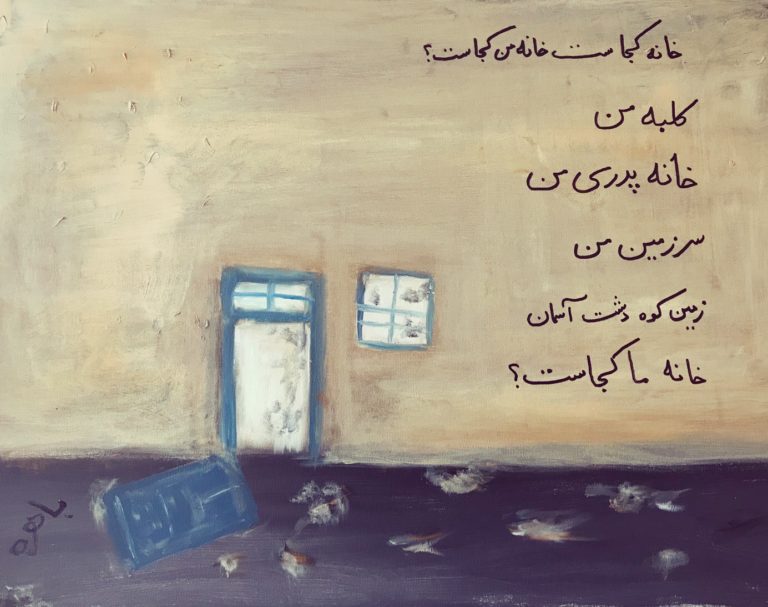

Troubling the Home/Land in Showtime’s Homeland: The Ghost of 1979 and the Haunting Presence of Iran in the American Imaginary

In my close reading of the drama series Homeland, I illustrate how the divisive pull between “fascination and contempt, desire and disgust” as well as the “simultaneous embracing and disavowal” that cultural critics argue define Iranian Americanness become embodied in the character Fara, a young Muslim Iranian American woman recruited into the CIA for her language and technical skills. This essay asks, among other questions: what does it mean to have anxiety over your birthplace or ancestral homeland? What does a “simultaneous embracing and disavowal” do to a person over time? I argue that as a consequence of how her body is read, Fara is continually denied access to a home and a land and ultimately becomes discarded after performing her role as an agent of the state apparatus. In addition, this essay considers how the ghost of the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979 is frequently invited to speak as an origins myth for contact between the US and Iran that subsequently shapes the lived realities of Iranian Americans nearly forty years later.

Review of Archaeologies of Touch: Interfacing with Haptics from Electricity to Computing by David Parisi (University of Minnesota)

Archaeologies of Touch announces itself as an opening salvo for a new media studies subfield capable of addressing this ongoing haptic reconstruction of our media environment. Parisi charts a genealogy of haptic interfacing that begins with seventeenth-century experiments using electrostatic generators and culminates in the latest projections for virtual reality. Over several centuries, we have become rendered “haptic subjects” through an “ongoing cultural training” (43) though “tactile media”—a “shifting assemblage composed of technical elements, embodied sensations, and cultural practices” (97). No longer aiming to stimulate the full surface of the flesh, what now counts as touch-based media assures but one or a few points of contact between the tip of the finger and the screen. Far from fulfilling the fate of electronics by rebalancing the human sensorium, haptic feedback as we know it today seems a step in the opposite direction. Parisi closes his book with a spirited call to action insisting on the need for an interdisciplinary subfield of haptic media studies, on par with visual cultural studies and sound studies.

Review of The Pink Tide: Media Access and Political Power in Latin America edited by Lee Artz (Rowman & Littlefield)

The ‘Pink Tide’ refers to the unprecedented succession of electoral victories of socialist-leaning populist presidents in the region, starting with Chavéz’s victory in 1998. This anthology explores media reforms in countries that most consistently reelected progressive candidates, specifically Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Uruguay, and Brazil. Through these case studies, Artz seeks to show that the primary indicator of democracy and social justice is the extent to which governments give the population direct access and control of the means of communication. Despite the complexities of the different cases, Artz presses that public participatory media, by promoting and prefiguring a socialist society, is an integral part of the democratic struggle that must be actively and continuously pursued by social movements.

Review of Global Entertainment Media: A Critical Introduction by Lee Artz (Blackwell)

Artz gives overwhelming evidence of how the cultural hegemony of individualism and consumerism is promoted everywhere by transnational media corporations (TNMCs), so that current social relations in capitalism are reproduced and reinforced. The reader can get a clear outlook of TNMCs and their impact on the diversity, hybridization, and standardization of global culture and outlooks.

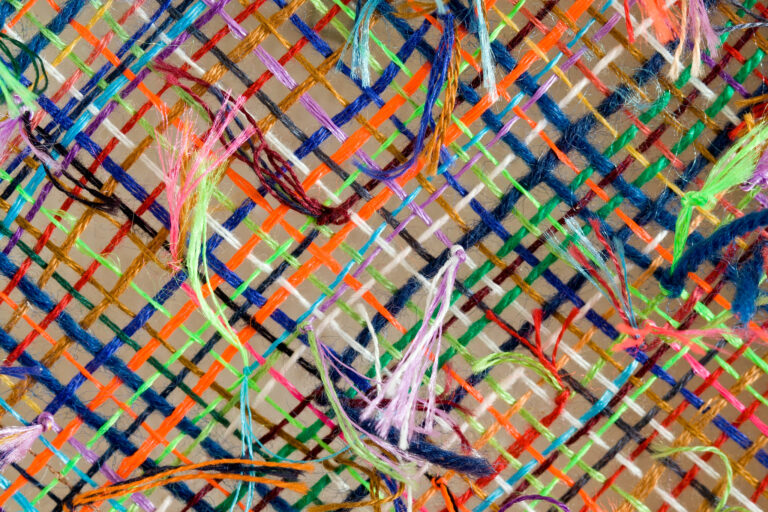

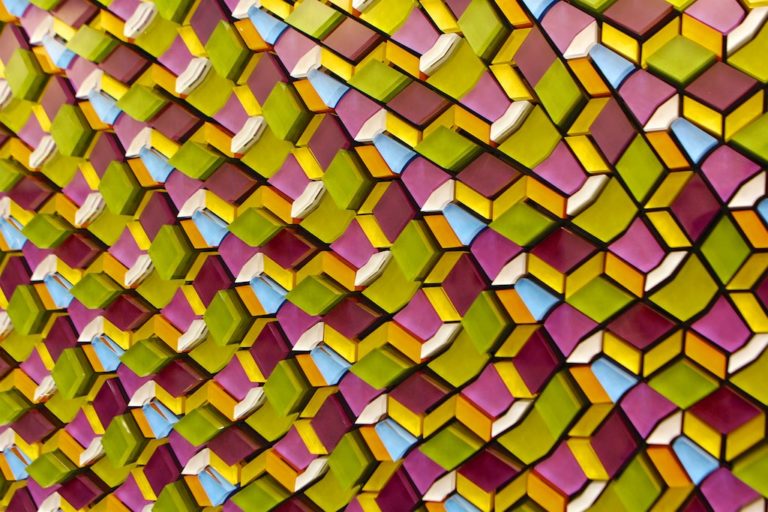

Make(r) Space, Making Space: A Media Ecology in Two Parts

The pop-up maker space hosted by the Media Interventions working group of the Cultural Studies Association at the 2014 annual meeting, ‘Ecologies: Relations of Culture, Matter, and Power,’ is a collaborative intervention into the typical structure of academic conferences in the interdisciplinary humanities and social sciences, whose genres and formats tend to privilege established scholars, disciplinary paradigms, the new, and above all a mindset in which the resources attached to ‘professionalization’ are governed by scarcity. Held concurrently with the main conference schedule at the University of Utah’s historic Pierre Lassonde House, the maker space showcases the work of artists, activists, media practitioners, performers, researchers, and amateur ‘makers,’ inviting conference attendees to engage the material not merely as spectators but as active participants in the collective meanings of the event. In doing so, it quite literally makes space for multimodal methods of knowledge production that decenter the individual and scramble the dominant temporalities of academic labor. This two-part essay describes the maker space as media ecology in the process of unfolding across multiple time frames (and time zones) and through unevenly distributed agencies as well as affective states. The first part documents the process of making a space for making, while the second attempts to partially capture and re-present the event itself through digital photography, video clips, sound snippets, links, maps, and other media ancillary to the maker space. In reading, watching, listening, touching, clicking, and otherwise attending to what we are making, you become integrated into the circuitry of our affections: the queer collection of things that comprise media ecologies.