In June 2017, the designer of the virtual reality technology Oculus, Palmer Luckey, co-founded a defense technology company called Anduril. The company’s first project was Lattice, an artificial intelligence system consisting of high-tech, low-cost sensors networked together to detect human presence at the US–Mexico border and send push alerts to notify US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents in real time. Lattice’s promotional mock interfaces feature satellite images of the border terrain, animated graphics, and what looks like close-circuit video footage of people running in the desert. Upon receiving a push alert, CBP agents strap on a pair of VR goggles to see a bird’s-eye view of the border by toggling between each sensor’s individual streams. Describing Luckey’s pitch to the US Department of Homeland Security, writer Steven Levy characterizes Lattice as a “sci-fi fantasia” that “us[es] off-the-shelf sensors and cameras, connect[s] them in a network, and make[s] something in the spirit of Google Maps and Pokémon Go.”1 The allusion to popular digital media in this description reveals much about how the borderlands are conceptualized by Silicon Valley speculators and their partnering state agencies. Media facilitates virtual forms of thinking about the border both by offering the reference points for the new technology being developed (Google Maps, Pokémon Go, Call of Duty) and by providing the actual tools through which these ideas can become actionable.2 As modes for imagining and creating, media technologies are particularly well suited to facilitate that transition between the virtual and the actual: the “spirit of Google Maps and Pokémon Go” quickly becomes the militaristic apparatus that targets brown bodies at the border.

In this article, what I call the “infrastructures of the border” refers to the sociotechnical systems that maintain the geopolitical boundary (checkpoints, bridges, surveillance cameras, weapons) and to the conceptual frameworks that shape popular ideas about what borders are and what they are for. Silicon Valley entrepreneurs’ references to popular digital media in the pitching and development of actual technologies for CBP agents reveals how much the physical and conceptual infrastructures of the border are intertwined. These references also implicitly suggest the racial mechanics undergirding the construction and maintenance of border infrastructures. As Daniel Nemser argues, race became thinkable in the colonial context through spatial disciplines (e.g. cartography or urban planning) and racialization took place through physical interventions in the landscape. Colonial infrastructure projects enabled the consolidation of racial categories by allowing “groupness” to emerge and by naturalizing segregation.3 In contemporary times, infrastructure projects continue to naturalize segregation through physical means: the US border wall stands as one of the most vulgar examples of this. Race continues to be a question of space as much as it is a question of populations and, as the Lattice example illustrates, the infrastructures of race in the border context increasingly include digital spaces in addition to physical ones.

If digital networked media actively participate in the nation-state’s and corporations’ efforts to imagine and manage the borderlands, then these media can also help us make sense of, and devise alternatives to, the visual, conceptual, and ideological infrastructures sustaining such efforts. This article pursues such a claim by analyzing one particular infrastructure of the US–Mexico border—underground tunnels—within the first-person shooter (FPS) console game Call of Juarez: The Cartel (Ubisoft, 2011). The Cartel is the third installment in the video game series Call of Juarez, a riff on the popular Call of Duty series but set in the US–Mexico border. The game follows three rogue law enforcement agents tracking down leaders of a trafficking cartel. Although I sometimes reference other media that deploy underground tunnels similarly, a sustained interrogation of The Cartel will offer insight into how its digitally animated border tunnels encode the infrastructures of race that Nemser argues stretch back to colonial times. Border-themed video games often borrow on colonial tropes and ideologies by creating playable narratives that invoke the untamable frontier and position racialized subjects as Other. Through digital modes of representation and interaction, these games encode the racialization processes that continue to shape popular imaginings of the border.

An analysis of the narrative and procedural work of tunnels within an ostensibly reactionary video game demonstrates how border infrastructures structure and shape specific forms of racial and colonial violence. The argument of this article follows Tara Fickle’s claim that “the infrastructure of gaming [is] itself a raced project.”4 Tracing a symmetry between the racial logic undergirding spatialized systems of oppression and the ludic logic that presents games as games, Fickle compellingly argues that we must understand racialization as a “location-based technology that has been seamlessly automated into the interface of everyday life.”5 If we understand racialization as a ludic logic, as a series of rules that encode hierarchies by limiting what some subjects can do and what others cannot, then video games like a first-person shooter pointedly illuminate the racial infrastructures of the border.6 Telescopic modes of visualizing the border like those proposed by Lattice inherently position border agents in the role of active watcher and shooter while all bodies present in the borderlands (e.g. migrants, Indigenous folks) are always already targets of scrutiny and violence. Analyzing the narrative, design, and procedural elements of The Cartel succinctly demonstrates how digitally animated renderings and their algorithmically determined forms of interaction shape the racial infrastructures of the border.

By “infrastructures” I refer not only to the structures themselves, but also to the connections between physical substrates and conceptual frameworks. As anthropologist Brian Larkin argues, the impact of infrastructures goes beyond their technical capabilities because they “encode the dreams of individuals and societies” in such a way that social ideals and fantasies can be “transmitted and made emotionally real.”7 The interrelated material and semiotic features of infrastructures means we should approach them as “generative structures,” or frameworks for building systems and environments that embody social values.8 Theorizing the border tunnels of The Cartel in this capacious understanding of infrastructures allows us to uncover the fantasies and social values embedded in virtual representations of the borderlands.

The first two sections of the article trace the genealogies of the ideologies embedded in a border-themed game like The Cartel, both as a virtual medium and as representation of the border as an untamed frontier. The next two sections analyze how the game’s genre and its level design mobilize the tunnel figure to re-imagine the space of the border while simultaneously reinforcing the dominant racial infrastructures of the border. The Cartel’s digital animation renders underground tunnels in imaginative ways yet the game’s specific form of interactivity, i.e. how players are able and unable to traverse these animated structures, circumscribes the experience of the border underground. While digital aesthetics may animate a dynamic space of possibility, the logic of the first-person shooter reins in the expansiveness of animated space by restricting it to an interactive experience of tunnel warfare. As an ideological orientation to the border underground, tunnel warfare explains how the game’s rendering of the underground environment through algorithmic corridors channels the players’ purposive motion into a space of direct confrontation and racial violence. This video game’s interactivity and digital animation act as racial infrastructures of the border by “making emotionally real” the (until now) unrealistic threat of tunnel warfare. The concluding section explains that, since the game’s design makes racial confrontation the most effective form to win the game, we must understand playing at tunnel warfare as a form of projecting old racial hierarchies into new, untapped border spaces.

The Politics of Virtual Media

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the founder of a virtual reality company would become interested in designing and developing media technologies for border policing. Borders are “virtual realities in the most literal sense,” argue Eszter Zimanyi and Emma Ben Ayoun, because they “project national and political imaginaries onto physical bodies.”9 The virtual reality of the border refers both to the current forms of media-enabled visualizations of control and to the emergent explorations of possible border alternatives. Throughout this article, I refer to video games and their use of animation as virtual media not only because of the technical affordances of computer-generated spaces but also because of these media’s capacity to represent what has yet to be actualized.10 If the virtual remains in a state of potential until given form, often through mediation, then virtual media engage in speculation, or practices that form conjectures, make estimations and projections, and look into the future so as to hypothesize. Virtual media project alternative futures by actualizing them in interactive forms. These technologies are thus not mere conduits for representing the border space; rather, they actively participate in the creation of space and in the encoding of dominant or resistant ideologies onto that space.

Interactive representations of the border hold significant sway in envisioning its features and its politics. The controversy over Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter 2 (Ubisoft, 2007), for example, centered on the game’s depictions of Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, as a lawless space in need of military intervention. At the time of its release, both the mayor of Juarez and the governor of Chihuahua condemned the game for promoting xenophobic ideas about Mexicans living in the border state and dissuading people from visiting the border city.11 Even without referencing specific locations, games about the US–Mexico border can reinforce racist stereotypes in their playable dynamics, as in the case of Smuggle Truck (Owlchemy Labs, 2011).12 Scholars have therefore argued that critical analysis of video games should be central to discussions of border and Latinx politics in the United States.13 Because “virtual experiences are contributing ever more to the way we live and understand our real lives,” Phillip Penix-Tadsen calls for a Latin American ludology that takes seriously how players interact with the region in the virtual sphere.14

In the case of the borderlands, the frontier ideology that promises an untamed expanse in need of intervention by white settlers finds its analogue in the ideology of interactivity promised by video games. For Mary Fuller and Henry Jenkins, these interactive virtual spaces are rife with colonial paradigms in that they “open new spaces for exploration, colonization, and exploitation, returning to a mythic time when there were worlds without limits and resources beyond imagining.”15 If by now the borderlands have been fully occupied and exhausted by the two nation-states that lay claim to them, virtual depictions of these spaces recycle the colonial fantasy of finding the lands untouched and ripe for settler occupation. This representation of open virtual spaces dovetails with the interactive narratives afforded by video games. The connection between game space and narratives of exploration lies in “the transformation and mastery of geography—the colonization of space” since progressing through the levels of a game is quite often contiguous with progressing through its world.16 Yet, as Soraya Murray argues, representations of a landscape within games reveal “ways of seeing the landscape, but as a representation of something that is already a representation in its own right.”17 While virtual representations in video games shape ideologies about the space depicted, their interactive form of representation already draws attention to its own constructedness. The value of critically examining how a reactionary video game constructs the borderlands is not only about identifying these representations as inaccurate but also about learning how these representations are built in the first place.

Then there is the question of play, or the strategies that players undertake within the constraints of the game design. How players interact with the space of video games has real implications for how this space comes to matter in the world. Games create “worlds with values at play,” argues Miguel Sicart.18 Players engage with the spaces depicted through the rules of the game. These rules have implied values within them, particularly about which forms of action are preferred or discouraged. There are ethics involved in rule-making and in playing, as users choose to follow, push at, or cheat these rules. When games take up already culturally loaded spaces in their playable narratives, we must attend to how the values inherent in the rules of the game resonate with the ideologies of that space in the real world. “There is no magic circle,” Mia Consalvo reminds us,19 because in-game behaviors often reflect players’ extra-game lives, revealing the porousness of the boundaries between territories of play and the lived world.

In particular, the first-person shooter game interpellates players as the sole causal force within the fictional world. The FPS’s brand of interactivity makes the player individually responsible for the decisions that affect gameplay while the game’s design already circumscribes the possibilities for action. Critically analyzing the doublethink inherent in digitally animated play sequences of tunnels offers one way to parse out how interactive media’s affordances enable particular ways of thinking about the current formation of the border and its potential alternative formations. The point is not to evaluate whether or not audiences believe that border tunnels are in fact as wide and high as depicted in digitally animated sequences. Rather, this analysis focuses on how virtual depictions of the border reveal the parallels between media-enabled forms of perception and the ideological alignments with border enforcement. If the infrastructures of the border include those physical structures and cognitive frameworks that entrench our current understanding of how divisions between states ought to be established and enforced, then animated tunnels thwart realistic expectations about the reliability and stability of such structures and frameworks. At the same time, these virtual depictions can create new spaces to repeatedly play out longstanding colonial and racial dynamics.

Frontier Narratives and the Mexican “Other”

The Cartel is the only game in the Call of Juarez series set in contemporary times. The installment proves generative for analyzing media tropes about the border because, by virtue of its failures in design and story, it makes explicit not only the racist and colonialist tropes underpinning frontier narratives but also how these tropes take shape in the mediated depiction of space. Frontier narratives have long been a foundational fiction of the United States as a settler-state and erstwhile colonial outpost of the European metropolis of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The “myth of the frontier” first served to explain and justify the establishment of the American colonies: waging a “savage war” with the indigenous peoples of the continent established the colonists’ self-identity and racial supremacy.20

The frontier as the expansive space to articulate conflicts between civilizations has long been a trope in popular culture and media, particularly through the genre of the western. The western allowed for the strict delimitation of good guys and bad guys in moralistic narratives set within purportedly uncharted and unruly lands. Media historian Thomas Schatz argues that the significance and impact of the western as the United States’ “foundation ritual” has been most clearly and effectively articulated in cinema. Filmic depictions of limitless vistas projected “a formalized vision of the nation’s infinite possibilities” which served to “‘naturalize’ the policies of westward expansion and Manifest Destiny.”21 The genre mutates to articulate various different anxieties about the nation, masculinity, and spatial control. Adding the affordance of interactivity, video games have likewise mobilized the tropes of the lawless frontier by creating virtual spaces that allow players to “play at colonization.”22 Film and television neo-westerns of the mid-2000s and early 2010s drew on these tropes to tell stories about these renewed anxieties at the turn of the twenty-first century.23 Neo-westerns have also come to represent the US-centric anxieties about the integration of the American hemisphere as a result of economic globalization and the increased transnational migration of people and goods.24 The Call of Juarez video game series draws on this new wave of interest in the western, connects it to the first-person shooter, and, in the process, finds resonances between the racist and colonialist tropes of both genres. The Cartel evidences the most pronounced examples of these resonances.

The racist elements of The Cartel have been well-documented by popular critics. Early in the game there is a level called “Gang Bang” where the law enforcement characters have to “incite gang violence” in a district of the game’s version of Los Angeles. In this level—and only in this level—players unlock an achievement called “Bad Guy” for killing at least forty characters. Importantly, all the non-playable characters (NPCs) that players would need to kill to unlock said achievement are black men. Another level alludes to the issue of sex trafficking around the border region by presenting it as if Mexican drug lords kidnap American white women to sell as sex slaves in Mexico. This framing falsely portrays the flow of sex trafficking as it currently occurs in the US–Mexico context, erasing the fact that most often Mexican women are kidnapped to service American clients. The level also builds on decades-old racist myths perpetuated by media about people of color conducting white slavery.25 In their review of the game, the educational collective Extra Credits explains that The Cartel “might be the most racist game [they’ve] ever played by a major publisher.”26

Racist portrayals of Mexicans in US popular media have a long history, as detailed by the work of Charles Ramirez Berg. Stereotypes such as el bandido, the drug runner, and the inner-city gang member are ahistorical and decontextualized representations that, through repetition, become “part of the narrative form itself—anticipated, typical, and well nigh ‘invisible.’”27 Despite repeated calls from advocacy groups for more varied portrayals, these stereotypical depictions continue today. As Jason Ruiz demonstrates, critically acclaimed neo-westerns in cable television dramas like Breaking Bad present stories about white male (anti)heroes defeating Mexican villains, thereby perpetuating the “Latino threat narrative” that positions these brown subjects as inherently threatening to the body politic of the United States.28 When such rhetoric then infiltrates the realm of policy, it shapes how Latinx bodies come to matter in popular discourse.29

As part of popular media, video games likewise frequently activate these stereotypes. Indeed, The Cartel falls within what Phillip Penix-Tadsen calls “contras games,” which “situate Latin American culture within the realm of paramilitary warfare” and whose narrative presents Latin Americans “only as the anonymous enemy contra the American hero.”30 Analyzing the tunnel-crossing moments in the game exposes yet another iteration of these long-standing racist and colonialist tropes. Moreover, The Cartel mobilizes the FPS genre to set up an interactive conflict between the game’s playable antiheroes and a series of unnamed, indistinguishable Mexican NPCs. By encoding and making playable racist and colonialist tropes, this first-person shooter recasts the borderlands as a paramilitary warzone against the infiltration of brown bodies into the United States.

Tunnel Warfare and the First-Person Shooter

The narrative and procedural work of tunnels within this reactionary video game illustrates how border infrastructures perpetuate specific forms of racial and colonial violence. In particular, The Cartel mediates what has been called “tunnel warfare.” As a concept popular in defense and military research, the idea of tunnel warfare recasts the potential emergence of underground border tunnels not only as elements of drug and gun trafficking but also as active sites for the undertaking of invasion and extermination efforts akin to those of a foreign-set war. Fighting within tunnels has long been an important albeit unremarked feature of modern wars.31 Military historians argue that while it does not “share the glamor” of air or sea warfare, armed conflicts in tunnels have often had decisive effects in the history of modern human conflict.32 The prolonged engagement in underground fronts during the Vietnam War represents a notable example in the history of the US military.33 More recently, the concept of tunnel warfare recurs within defense contractor sectors interested in developing new technologies to carry out such warfare underground. Think tanks based out of the United States look particularly to the Israel Defense Forces’ attacks on Palestinian tunnels in the occupied territories and hypothesize how such actions could benefit policing efforts in US-occupied areas and across the border.34 According to such research, the subterranean must become “an operational environment” and armed forces should actively prepare for future conflicts underground.35 In the twenty-first-century version of tunnel warfare, war must be waged on the Global South subjects trying to use the tunnels to purportedly access Global North’s territory and resources.

To understand how tunnel warfare comes to figure the border as a lawless arena, consider another famous media text that also features a tunnel shootout, Denis Villeneuve’s thriller Sicario (2015). In one of the film’s iconic sequences, agents of the inter-agency task force enter an underground border tunnel in the middle of the night. The agents disperse across what appears to be a long corridor with smaller hallways branching off. In the course of the ensuing shootout, the film’s protagonist Kate (played by Emily Blunt) is almost shot from the corner of one of these hallways. Asked to stay close behind by her colleague, she instead separates from the group of agents and heads down her own path. She comes out the Mexican side of the tunnel and discovers the rogue agent Medellín (played by Benicio del Toro), who has just shot a trafficker in the head and is taking a Mexican police officer hostage. When confronted, Medellín shoots Kate twice in her bulletproof vest and leaves her convalescing while he escapes to carry out his secret mission in the south side of the border.

That Kate’s confrontation with Medellín and the revelation of his nefarious plan play out in and through a border tunnel is significant in a number of ways. First, it takes the dominant representation of tunnels in media as avenues for the traffic of drugs northward to the US and reverses it. Second, the sequence frames the character’s moment of revelation in terms of her traversing the tunnel, as she comes out the other side to discover what has been planned throughout the film unbeknownst to her. Finally, this climactic action sequence and its resolution are also the apex for the film’s reactionary politics. Throughout the film, Sicario’s narrative centers on wearing down its idealistic female protagonist from the eager proactive agent she embodies at the beginning to the disillusioned failed operative role she assumes at the end. The film consists of a series of rogue missions, each increasingly more violent, that put Kate and her partner Reggie in constant danger while sidelining them from the decision-making processes of the task force. The tunnel shootout briefly allows Kate to separate from the norms of the group, only to be punished for diverging from the warfare mentality of the rest of the agents. Her personal defeat functions to reinforce the worldview of her male counterparts in the task force: that the border is a dangerous place where rules of law do not apply and where the only course of action is masculinist vigilante justice.

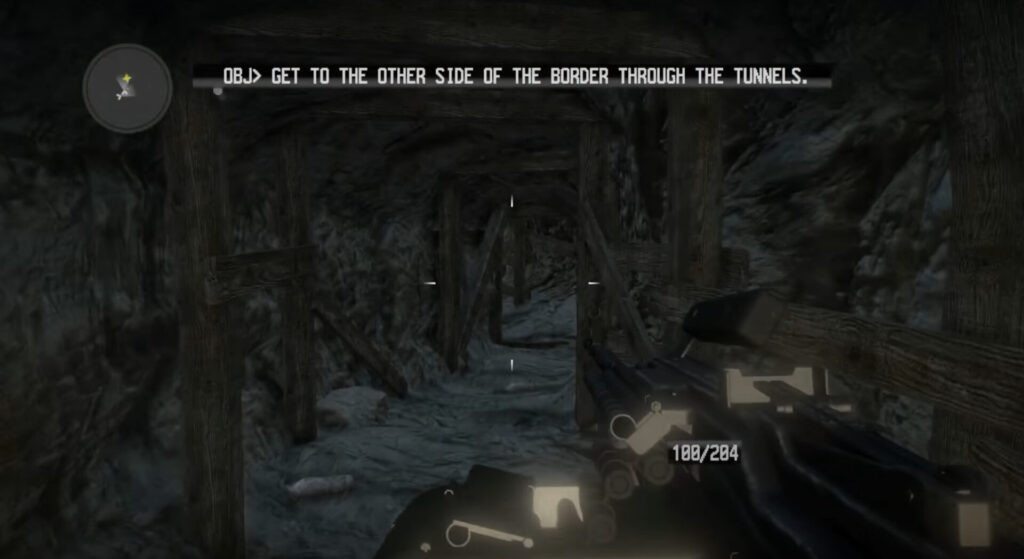

The tunnel level in The Cartel likewise promotes these ideologies yet situates them within the genre of the first-person shooter game. The first-person shooter game is defined by two main characteristics: its perspective (“first-person”) and its activity (“shooter”). In addition to the noticeable weapon in the foreground, the perspective of the FPS is the subjective camera, a type of point-of-view shot that “positions itself inside the skull of [the] character” and attempts to reproduce the physiology of embodied vision.36 As Alexander Galloway argues, the first-person subjective perspective is “so omnipresent and so central to the grammar of the entire game that it essentially becomes coterminous with it.”37 As the game’s central functions, the FPS’s subjective perspective and shooting activity work together to personalize gameplay (figure 5). The player moves the character through a series of environments, ranging from simple room-based mazes to more complex environments. Despite varying degrees of narrative and spatial complexity, “the ultimate goal in the first-person shooter is to traverse from point A to point B, ridding the environment of the enemies which inhabit it.”38 The FPS shooting activity is thus not only a playable action but also a mode of perception. To kill in a first-person shooter is to inhabit its environment.

This ideological mapping onto its mode of perception in the FPS illustrates why it is a preferred genre for military training. The identification structure of the FPS sets the player as the hero and casts the non-playable characters encountered throughout as villains to be eliminated. In the Wired article on Andruil, Palmer Luckey claims that the “DOD has been asking for what some people describe as Call of Duty goggles. Like, you put on the glasses, and the headset display tells you where the good guys are, where the bad guys are, where your air support is, where you’re going, where you were.”39 Luckey’s contention that the Department of Defense wants a media technology to perform the work of casting “good guys” and “bad guys” succinctly illustrates the common appeal of both this video game genre and digital technologies for border security: the illusion that the technology itself will mediate the world around the subject and map social ideologies into interactive interfaces in a straightforward way.

In the first-person shooter, to inhabit an environment is to shoot your way through it. From the outset, the game’s procedural structure casts its environments as spaces filled with dangers and enemies that must be eliminated. As Matthew Payne puts it, the first-person shooter acts as a “textual apparatus [that] locates the player as an agent of change in a universe where his or her choices are decisive plot points for a personalized war story” as well as a “cultural apparatus [that] targets political anxieties as opportunities for play and pleasure.”40 The game allows players to “play out” political anxieties in a manner that positions them as the main agents of change for addressing these anxieties. Addressing, however, becomes reduced to shooting their way out of a situation. Success is measured in hits. Amanda Philipps argues that, because games strip away the physical and psychological challenges of shooting, the gamer’s experience of shooting consists of visual acuity and well-timed reflexes multiplied by quantity of hits: “shooting to kill becomes a riskless, fast-paced, twitchy enterprise.”41 The first-person shooter’s direct, violence-forward approach further reinforces the colonialist tropes of the frontier narrative. In The Cartel, this approach renders the border as an untamed space and posits shooting as the way to deal with that space.

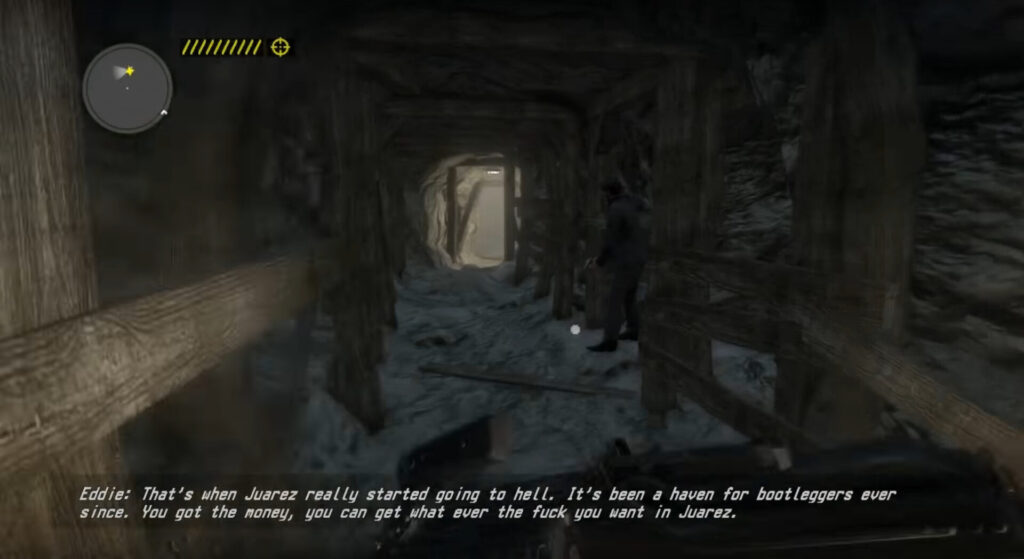

The game then centers (unnamed) Mexicans as the stumbling blocks within the series of corridors to traverse the border through the underground. As with its “Gang Bang” level, the men of color in The Cartel are reduced to non-playable characters whose sole purpose is being the targets for the players’ shooting. Yet, this racist figuration operates not only at the level of representation. Because of the subjective camera position of the first-person shooter, this procedural genre fulfills the ideological imperative to tell the player “where the good guys are, where the bad guys are . . . where you’re going, where you were” as Luckey puts it. The game’s procedural elements position unnamed Mexicans as criminals and limit players’ responses to shooting them. The subjective positioning of the player within the game and the design of the playable space themselves already establish specific roles that reinforce racial and gendered hierarchies.

Playing in Algorithmic Corridors

Plenty of scholars have addressed the formation of subjectivity within first-person shooter games,42 but fewer have written about the role of the setting where these subjective structures take place. First-person shooter games are notorious for their use of corridors in level design. Because the principal gameplay action requires a player to advance through a level shooting and avoiding being shot at, a FPS map usually consists of a series of rooms and corridors in any number of configurations. These configurations perform wayfinding functions for players and offer tactical spaces to retreat in between rounds of shooting. FPS games may feature elaborate architectures with several different floors, sometimes with openings to see above or below. They may also include strategically placed design choices such as stairs, ramps, and poles for moving vertically between floors. The tunnel space in The Cartel consists of only a single floor, and while the ceiling does not always appear when players run through the level, it is implied that the lack of high galleries prevent a player from getting shot at from above. Instead, the game level relies heavily on the corridor formations, particularly a recursive series of forking corridors, to offer wayfinding and to provide players with barriers to hide behind. Rocks, wooden panels, and corridor corners allow players spaces to retreat when being shot at.

Because of this design simplification, The Cartel neatly illustrates the centrality of corridors to the first-person shooter as both an enabling mechanism and a restrictive feature. Corridors function as what Ian Bogost calls a “procedural figure,” a unit operation that allows for a range of expressive practices.43 These basic unit operations provide options for procedural forms, like a game engine or a user interface, to be applied towards a variety of goals. The assemblage of these forms creates procedural genres like the first-person shooter. The corridor therefore acts as a figure that can be taken up in any number of ways with distinct meanings and applications across genres. How these basic figures get taken up within the genre speaks to the forms of thought that the genre potentiates and restricts. In particular, because computational media has a native ability to “represent process with process,” a procedural genre like the first-person shooter mobilizes the figure of the corridor in significantly different manners from other textual or visual media.

Corridors may allow for different expressive functions in other types of games, but in the first-person shooter they are a fundamental engine to thinking about space and purposive action. Corridoricity becomes a central spatial design feature that reinforces this genre’s specific identificatory perspective and enables its central activity.44 The corridors set the spatial limits of how players move through the game: following linear paths and making decisions about trajectories at forks along the way. Michael Nitsche identifies five shared elements that allow individuals to create cognitive maps of fictional spaces: paths (or corridors), landmarks, edges or limits, crossroads, and districts.45 Individuals could produce different cognitive maps of the same space by privileging one element over another and structuring their mental image around their privileged element. In the case of FPS, corridors become the privileged elements for making sense of the game space. They enable the forward movement and, depending on architectural variations on their structure, facilitate or complicate strategies for attacking enemies. Corridoricity is therefore essential to the making sense of FPS game space both in terms of spatial recognition (the ability to navigate the game) and cognitive mapping (the understanding of the world proposed by the game).

Corridors as procedural figures in the first-person shooter also establish value judgements about how to interpret these spatial arrangements. Under the FPS logic, open spaces signify moments of vulnerability because the player could be at risk of attack from unseen foes. Game levels with multiple floors and openings between these floors dichotomize player action between hiding and advancing through the level through shooting. These open spaces present a world that requires choosing between offensive and defensive options. Players must evaluate and decide between distinct courses of action. Closed corridor spaces, in contrast, limit the opportunities for hiding, offering merely contingent and momentary instances of retreat. In turn, these closed corridor spaces not only facilitate but demand direct confrontation. Absent the possibility of a defensive position, closed corridor spaces propose attack as the only viable course of action; confrontation becomes tantamount to advancing through the level. To shoot is to move and to move is to succeed.

What is at stake in focusing on the corridoricity of the tunnel level as a procedural figure within The Cartel? As Tom Senior in PC Gamer notes, The Cartel’s “[game] engine is capable of throwing out environments of notable scale, but they’re always painfully linear wide corridors full of pop-up drug fiends and pop-in textures.”46 Other reviews of the game likewise noted the sophistication of the environment as a whole, but bemoaned the repetitiveness of the forking corridor structure for how little variety it allowed in terms of strategy. Undoubtedly, this is a failure in terms of the potential pleasures of playing the game. Little variation results in monotonous gameplay. Still, the repetitive “painfully linear wide corridors” instructively illustrate the mode of perception unique to playing through shootouts in tunnels as well as this mode’s attendant ideological implications. If, as Matthew Payne argues, the cultural apparatus of the FPS transforms political anxieties into opportunities for pleasure and play, then tunnels as the site for a shootout enable specific modes of perceptual engagement with border spaces and with the characters encountered therein: neo-colonization, direct confrontation, and racist extermination.

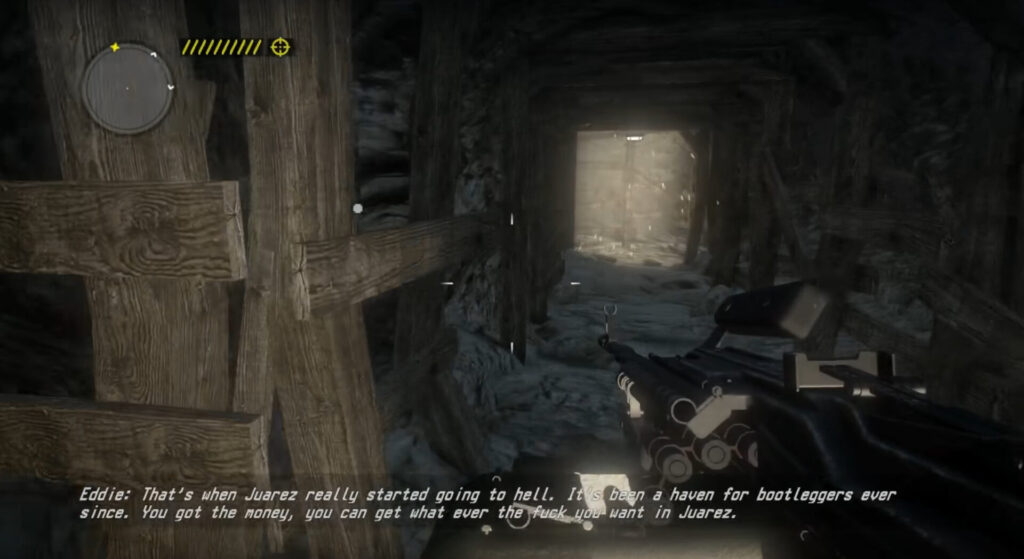

These modes of engagement feed into a frontier rationale for interpreting underground spaces. Early in the tunnel level, the player’s allies explain the history behind the tunnels:

Eddie: I’ve seen smuggling tunnels all up and down the border, but nothing like this one…

Kim: Some of those old Spanish forts had escape tunnels. This could be one of those…

Ben: Smugglers have been moving shit across the border ever since there was a border.

Kim: I wouldn’t be surprised if the mob used this tunnel during prohibition…

Through the characters’ dialogue, the game flattens a varied history of smuggling and tunnel building (fictional and nonfictional) into the same structure. The implication is that the tunnels the characters move through could stand in for all those trafficking structures that have existed throughout the history of the US–Mexico border. To be sure, the game’s narrative fails to make any self-conscious connection between these illicit acts and the playable characters’ own circumventing of the border through tunnels, concluding merely that as long as there has been a border, there has been smuggling. Yet, setting the game’s border crossing moment within the tunnels reveals the usefulness of these infrastructures to the conceptual reorganization of the border as a lawless frontier. The tunnels’ corridor structure transforms the border’s linear division into an expanded space of confrontation appropriate for the first-person shooter. As previously mentioned, the game presents only unnamed Mexicans-qua-drug dealers as the stumbling blocks within the series of corridors to traverse the border through the underground. The tunnels in the game stand not only as the site for illicit activities but also as the ground where the confrontation with, and extermination of, the Mexican “Other” becomes playable and pleasurable.

The affordances of digital animation and algorithmic processing within a video game like The Cartel produce a virtual version of the borderlands that is both expansive and restrictive. Digital animation allows the game to create an underground border space big enough to sustain multiple shootouts. Repetitive animated renderings of tunnels as the players move through the level for a prolonged period of time create an undifferentiated space of the border underground. The algorithmic reproduction of these animated tunnels also serves to extend the time it takes players to traverse this undifferentiated space (particularly in contrast to the time it takes to watch the shootout in Sicario) and to reinforce the ideology of direct confrontation enabled by its corridoricity. Ultimately, however, these affordances mobilize almost exclusively reactionary means. The expansion of the border underground, the temporal elongation, and the procedural re-casting of movement within the first-person shooter logic serve to reinforce the lawlessness of the border region and to uphold violent self-assertion as a means to traverse the region.

Conclusion: The Efficiency of Playing White Supremacy

Unlike other digitally animated representations of border tunnels, video games offer the opportunity for interaction, where players can select how to engage with the structures within the confines set by the game’s design. As Adrienne Shaw productively explains, “analyzing texts tells us how the audience was constructed” and the meanings embedded in these texts while studying the audience “helps us make sense of where these meanings go after they are constructed.”47 While an audience analysis of The Cartel is beyond the scope of this article, I want to end by suggesting how the game’s design simplification incentivizes players’ decisions to replicate the racist infrastructures created by the tunnel level. For Christopher Patterson, games expose race not only as history or culture but also “as tactics and strategies for either winning or disrupting the order of things.”48 Adhering to specific “winning” strategies sometimes means embracing the dominant tensions, fears, and anxieties that shape popular notions about race. By uncritically engaging with the game’s corridic structure, players of The Cartel could fall into its circumscribed approach to traversing the level that replicates racial hierarchies of white agents eliminating Mexican NPCs.

Consider how the walkthrough for The Cartel on GameFAQs, a popular game discussion site run by Game Spot, suggests traversing the tunnel level:

Follow the waypoint markers through the tunnel and you will eventually happen upon some enemies. The first group will just be a few in the hallway, which are easy enough to dispatch. The next will be a small group that has the high ground and have [sic] shored up behind some crates and rocks . . . . After dealing with those enemies, head through the door and head through the tunnels, following your waypoint and killing the odd enemy along the way . . . . Head toward your waypoint and suddenly a random guy will yell out that he’s blowing up the tunnel. Run like hell straight forward and you’ll eventually be caught [by] a rock slide and be separated from your partners. Follow your waypoint marker through a long, long corridor of debris before finding yourself with your teammates once more.49

This description encapsulates the corridor structure of the tunnel level and how this structure systematizes the FPS logic of shooting as moving. The repeated recourse to the waypoint marker is telling in this regard: whenever the level presents a fork in the tunnel corridors, the marker can help the player decide which hallway to choose. The mention of “the odd enemy along the way” and the instructions to head straight ahead repeatedly suggest that the main point of the level is running through the corridors and that the NPCs are merely obstacles in the player’s movement through these corridors.

Certainly, players could choose not to follow the most efficient play strategy presented by the game. Players could perform what Espen Aarseth calls “transgressive play,” a tactic that serves as “a symbolic gesture against the tyranny of the game, a (perhaps illusory) way for the played subject to regain their sense of identity and uniqueness through the mechanisms of the game itself.”50 But such transgressive play would likely be more troublesome, tiring, and time-consuming than following the straightforward strategy of embracing the game’s use of corridors as avenues for racial violence. Quite literally, perpetuating the racist status quo is the path of least resistance. If racial frames emerge from the selection of play strategies as much as from the game’s symbolic representation, then the efficient way of traversing the tunnel level in The Cartel requires subscribing to a tunnel warfare mentality of shooting unnamed Mexican NPCs in order to cross the border. Implicit in this “efficient” play strategy also lie the twin reactionary ideologies of perceiving the borderlands as zones of conflict and of approaching border-crossing as an individualistic, violent endeavor.

The specific imagination of underground tunnels presented in The Cartel results from the game’s generic conventions, its racist narrative tropes, and the specific game mechanics of the first-person shooter. Importantly, the game reveals how “tunnel warfare” can emerge as an ideological perspective even when there is no physical or material support for it. In reality, Border Patrol agents continuously reveal their hesitation to venture into a tunnel without precautionary measures for fear of finding a trafficker inside. Were they to come face-to-face with someone inside the tunnel, both parties would immediately be exposed as there would be nowhere to hide or retreat to. In contrast, the animated tunnels of The Cartel expand the space of the tunnel to allow for spaces to hide and shoot at enemies from, refiguring the underground space as one conducive to armed confrontation. This example of virtual media gives life and form to the idea of tunnel warfare as a future possibility for engaging with the border: a novel and imaginary rendering of the space that nonetheless replicates current forms of racist confrontation. By mobilizing the procedural elements of the first-person shooter, the game sets this confrontation as necessary for exploring the space and moving through it. Its corridoricity then limits the scope of possible strategies for traversing them, effectively circumscribing players’ possible actions to shooting specifically and to warfare generally. Ultimately, these animated tunnels reaffirm the ideology of tunnel warfare by opening up the possibility of such underground confrontation to occur; by implementing a strict corridor structure on the expanded underground space; and by limiting the course of action to shooting as moving.“

As military technology today makes clear,” writes Eugene Thacker, “the VR videogame interface is the ‘real world’ of navigation, combat, and warfare.”51 The Lattice example described at the beginning of this article offers a clear example of this assertion. Virtual reality creators can seamlessly transition into developing militaristic technologies for border enforcement because so many of their fictional creations already present the forms of seeing and acting that render the borderlands as spaces of conflict and racial violence. That parallel is by design. As Tara Fickle argues, even purportedly innocuous games borrow racial frames for seeing and organizing the world, frames which then become actionable when racialized subjects experience violence for transgressing those norms in real, physical spaces.52 Video games likewise function as inextricable infrastructures of the border insofar as these media enable speculative interactive audiovisual representations of the borderlands and encode dominant ways of interacting with that space. In the “virtual reality” of the US–Mexico border, to follow Zimanyi and Ben Ayoun, media test out alternatives that can then become physical realities. The virtual ways of seeing and interacting supported by these media have real, physical consequences when translated into continued violence to the bodies and ecologies present in the border space.

Notes

- Steven Levy, “Inside Palmer Luckey’s Bid to Build a Border Wall,” Wired, June 11, 2018, https://www.wired.com/story/palmer-luckey-anduril-border-wall. ↩

- For another example, see Jared Keller, “The inside story behind the Pentagon’s ill-fated quest for a real life ‘Iron Man’ suit,” Task & Purpose, May 6, 2020, https://taskandpurpose.com/military-tech/pentagon-powered-armor-iron-man-suit. ↩

- Daniel Nemser, Infrastructures of Race: Concentration and Biopolitics in Colonial Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017), 4. ↩

- Tara Fickle, The Race Card: From Gaming Technologies to Model Minorities (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 3. ↩

- Fickle, The Race Card, 7. ↩

- As Christopher B. Patterson notes, the first-person shooter game finds its origins in Texas. The Dallas-based studio id Software produced three games that “came to define the first-person shooter, beginning in 1992 with Wolfenstein, then popularized with Doom in 1993, and made three dimensional with Quake in 1996.” See Christopher B. Patterson, Open World Empire: Race, Erotics, and the Global Rise of Video Games (New York: New York University Press, 2020), 300. ↩

- Brian Larkin, “The Poetics and Politics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013): 333, https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522. ↩

- Shannon Mattern, “Scaffolding, Hard and Soft: Media Infrastructures as Critical and Generative Structures,” The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities, edited by Jentery Sayers (New York: Routledge, 2018), 323. ↩

- Eszter Zimanyi and Emma Ben Ayoun, “On Bodily Absence in Humanitarian Multi-Sensory VR,” Intermédialités / Intermediality 34 (2019), https://doi.org/10.7202/1070876ar. ↩

- Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, “The Actual and the Virtual,” Dialogues II, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 148–52. ↩

- See Tim Surette, “Mexican Mayor Slams GRAW2,” GameSpot, March 9, 2007, https://www.gamespot.com/articles/mexican-mayor-slams-graw2/1100-6167149/; and Brendan Sinclair, “Mexican Governor Orders Seizure of GRAW2,” GameSpot, March 23, 2007, https://www.gamespot.com/articles/mexican-governor-orders-seizure-of-graw2/1100-6168009/. ↩

- Mark Brown, “Snuggle Truck iOS Game Ditches Immigrant Characters for Fluffy Animals,” Wired, May 3, 2011, https://www.wired.com/2011/05/iphone-snuggle-truck/. ↩

- See, for instance, Frederick Luis Aldama, “Getting Your Mind/Body On: Latinos in Video Games,” in Latinos and Narrative Media: Participation and Portrayal, edited by Frederick Luis Aldama (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 241–58; Osvaldo Cleger, “Procedural Rhetoric and Undocumented Migrants: Playing the Debate Over Immigration Reform,” Digital Culture and Education 7, no. 1 (2015): 19–39; Osvaldo Cleger, “Why Videogames: Ludology Meets Latino Studies,” in The Routledge Companion to Latina/o Popular Culture, edited by Frederick Luis Aldama (New York: Routledge, 2016), 87–100. ↩

- Phillip Penix-Tadsen, “Latin American Ludology: Why We Should Take Video Games Seriously (and When We Shouldn’t),” Latin American Research Review 48.1 (2013): 185, https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2013.0008. ↩

- Mary Fuller and Henry Jenkins, “Nintendo and New World Travel Writing: A Dialogue,” in Cybersociety: Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, edited by Steven G. Jones (Sherman Oaks: SAGE Publications, 1995), 58. ↩

- James Newman, Videogames (New York: Routledge, 2013), 109. ↩

- Murray, On Video Games, 168. Emphasis in the original. ↩

- Miguel Sicart, The Ethics of Computer Games (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011), 31–32. ↩

- Mia Consalvo, “There Is No Magic Circle,” Games and Culture 4, no. 4 (2009): 415. ↩

- Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-century America (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998), 11–2. ↩

- Thomas Schatz, Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmmaking, and the Studio System (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981), 46–47. ↩

- See Shoshana Magnet, “Playing at Colonization: Interpreting Imaginary Landscapes in the Video Game Tropico,” Journal of Communication Inquiry 30, no. 2 (2006):142–62, https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859905285320. ↩

- See, for instance, Michael C. Reiff, “Review of Hell Or High Water dir. by David MacKenzie,” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal 46, no. 2 (2016): 106–8; Fabian Orán Llarena, “Neoliberalism and Populism in Hell or High Water,” Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos 22 (2018): 247–73, http://doi.org/10.12795/REN.2018.i22.11. ↩

- See, for instance, Camilla Fojas, “Hollywood Border Cinema: Westerns with a Vengeance,” Journal of Popular Film and Television 39, no. 2 (2011): 93–101, http://doi.org/10.1080/01956051.2010.484037; and Kathleen Staudt, “The Border, Performed in Films: Produced in both Mexico and the US to ‘Bring Out the Worst in a Country,’” Journal of Borderlands Studies 29, no. 4 (2014): 465–79, http://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2014.982471. ↩

- See, for instance, Christopher Diffee, “Sex and the City: The White Slavery Scare and Social Governance in the Progressive Era,” American Quarterly 57, no. 2 (2005): 411–37, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2005.0025. ↩

- Extra Credits, “Call of Juarez: The Cartel – How Lazy Design Hurts Everyone,” May 17, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W0ci6rYOleM. ↩

- Charles Ramirez Berg, Latino Images in Film: Stereotypes, Subversion, and Resistance (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), 19. ↩

- Jason Ruiz, “Dark Matters: Vince Gilligan’s Breaking Bad, Suburban Crime Dramas, and Latinidad in the Golden Age of Cable Television,” Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies 40, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 37–62. ↩

- See, for instance, Kent A. Ono and John M. Sloop, Shifting Borders: Rhetoric, Immigration, and California’s Proposition 187 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002). ↩

- Penix-Tadsen, “Latin American Ludology,” 181. Emphasis in the original. ↩

- Daphné Richemond-Barak, Underground Warfare (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩

- Paul J. Springer, “Fighting Under the Earth: The History of Tunneling in Warfare,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, April 23, 2015, https://www.fpri.org/article/2015/04/fighting-under-the-earth-the-history-of-tunneling-in-warfare. See also Arthur Herman, “Notes From the Underground: The Long History of Tunnel Warfare,” Hudson Institute, August 26, 2014, https://www.hudson.org/research/10570-notes-from-the-underground-the-long-history-of-tunnel-warfare. ↩

- See John Penycate and Tom Mangold, The Tunnels of Cu Chi: A Harrowing Account of America’s “Tunnel Rats” in the Underground Battlefields of Vietnam (New York: Presidio Press, 2005); and Gordon L. Rottman, Viet Cong and NVA Tunnels and Fortifications of the Vietnam War (Oxford: Bloomsbury, 2012). References to this historical precedent now carry a xenophobic and racist framing of tunnel shutdown efforts. CBP agents wear “tunnel rats” shirts that recall the Vietnam War and the use of tunnels to fight the Viet Cong forces. See Steve Patterson, “Meet the Border ‘Tunnel Rats’ Patrolling Deep Underneath the US Mexico Border,” NBC Nightly News, August 27, 2016. ↩

- Homeland Security Research Corp., Israel Tunnel Warfare, August 2015, https://homelandsecurityresearch.com/download/Israel_Tunnel_Warfare.pdf . ↩

- See Matthew Cox, “Army Is Spending Half a Billion to Train Soldiers to Fight Underground,” Military Times, June 24, 2018, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2018/06/24/army-spending-half-billion-train-troops-fight-underground.html; and Patrick Tucker, “‘Underground’ May Be the US Military’s Next Warfighting Domain,” Defense One, June 26, 2018, https://www.defenseone.com/technology/2018/06/underground-may-be-us-militarys-next-warfighting-domain/149296/. ↩

- Alexander Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 41. ↩

- Galloway, Gaming, 63. ↩

- Andrew Kurtz, “Ideology and Interpellation in the First-Person Shooter,” Growing Up Postmodern: Neoliberalism and the War on the Young, edited by Ronald Strickland (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002), 113. ↩

- Levy, “Inside Palmer Luckey’s Bid to Build a Border Wall.” ↩

- Matthew Payne, Playing War: Military Video Games After 9/11 (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 56. ↩

- Amanda Phillips, “Shooting to Kill: Headshots, Twitch Reflexes, and the Mechropolitics of Video Games,” Games and Culture 13, no. 2 (2018): 145, https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015612611. ↩

- In addition to the authors already quoted, see Sue Morris, “First Person Shooters: A Game Apparatus,” ScreenPlay: Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces, edited by Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska (London: Wallflower Press, 2002), 81–97; Gerald Voorhees, “Play and Possibility in the Rhetoric of the War on Terror: The Structure of Agency in Halo 2,” Game Studies 14, no. 1 (2014), http://gamestudies.org/1401/articles/gvoorhees; Victor Navarro, “I Am a Gun: The Avatar and Avatarness in the FPS,” in Guns, Grenades, and Grunts: First-Person Shooter Games, edited by G. A. Voorhees, J. Call and K. Whitlock (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012), 63–88. ↩

- Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), 12–3. ↩

- In theorizing the corridoricity of the FPS, I am indebted to Kate Marshall’s examination of corridors in modernist literature. Marshall demonstrates how the corridor encodes in its own material structure the communicative aspects it represents: connection, movement, and division. Because of its self-reflective formal character, the corridor reveals the aesthetic, technical, and political operations that go into its creation. See Kate Marshall, Corridor: Media Architectures in American Fiction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013). ↩

- Michael Nitsche, Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), 162. ↩

- Tom Senior, “Call of Juarez: The Cartel Review.” PC Gamer, November 12, 2011, https://www.pcgamer.com/call-of-juarez-the-cartel-review/. ↩

- Adrienne Shaw, Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 63. ↩

- Patterson, Open World Empire, 49. ↩

- Game FAQs, “Call of Juarez: The Cartel: Guide and Walkthrough,” July 31, 2011, https://gamefaqs.gamespot.com/ps3/621206-call-of-juarez-the-cartel/faqs/62744. ↩

- Espen Aarseth, “I Fought the Law: Transgressive Play and the Implied Player,” in Proceedings of the 2007 DIGRA International Conference: Situated Play, edited by Akira Baba (Tokyo: University of Tokyo, 2007), 130–32. ↩

- Eugene Thacker, “Representation, Enaction, and the Ethics of Simulation,” First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game, edited by Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004), 75. ↩

- Fickle, The Race Card, 7. ↩