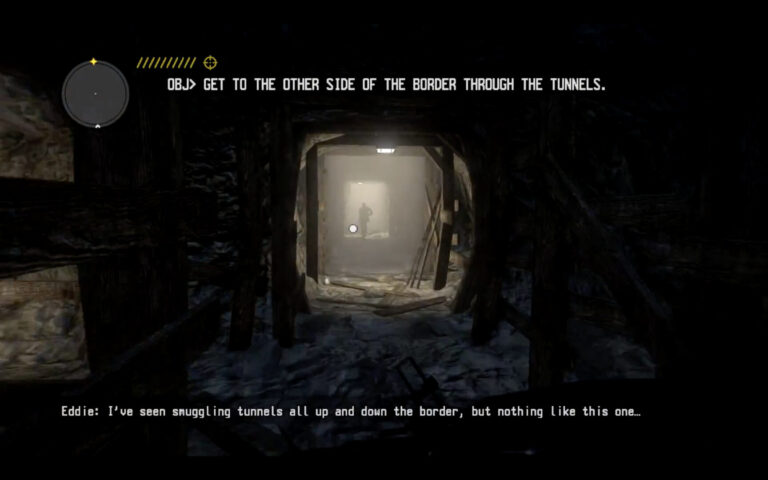

Digital networked media actively participate in the nation-state’s and tech entrepreneurs’ efforts to imagine and manage the borderlands. These media facilitate virtual forms of thinking about the border both by offering popular reference points for the new technology being developed (e.g. Google Maps, Pokémon Go, Call of Duty) and by providing the actual tools through which these ideas can become actionable. This article analyzes one such reference point within the first-person shooter (FPS) console game Call of Juarez: The Cartel (Ubisoft, 2011). Like other border-themed video games, The Cartel borrows on colonial tropes and ideologies by creating playable narratives that invoke the untamable frontier and position racialized subjects as Other. Through its virtual modes of representation and interaction, the game encodes the racialization processes that continue to shape popular imaginings of the border. While its digital aesthetics animate a dynamic space of possibility, the logic of the first-person shooter reins in the expansiveness of animated space by restricting it to an interactive experience of tunnel warfare, an ideological orientation to the border underground that channels the players’ purposive motion into a space of direct confrontation and racial violence. Analyzing the narrative and procedural work of this ostensibly reactionary video game demonstrates how border infrastructures structure and shape specific forms of racial and colonial violence.

Keyword: border

Review of Bans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary: Understanding U.S. Immigration for the Twenty-First Century by A. Naomi Paik (University of California Press)

A. Naomi Paik’s Bans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary responds to a trio of executive orders on immigration policy issued in the early days of Donald Trump’s presidency. Those orders sought to make good on campaign promises to further restrict immigration by banning citizens from Muslim-majority countries, allocating funds to expand a border wall between the US and Mexico, and ramping up home and workplace deportation raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Paik delineates how these legal barriers came to be by locating them in relation to the nation’s formative immigration policies, backlash to the liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s, and the global repercussions of neoliberalism. Highlighting the work of Indigenous activists, Paik eventually calls not only for the dramatic restructuring of the nation’s immigration system but also for the creation of a more just society based on relationships that reject the politics of inclusion and exclusion.

Border Trash: Recovering the Waste of US-Mexico Border Policy in Fatal Migrations and 2666

This article examines how discourses of waste and wastefulness are applied to the bodies of border crossers and border dwellers along the US-Mexico border. Using Josh Begley’s 2016 digital memorial “Fatal Migrations” alongside the fourth section of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, I examine how the matter of bodies plays an essential role in border policing. Forced into isolated and environmentally hostile areas, migrants are only visible through discarded objects, left behind during border crossing. As a result, American policy and discourse is able to associate migrant bodies with the trash they leave behind—effectively reducing migrant bodies to disgusting and ecologically dangerous. I look at “Fatal Migrations” to consider how the landscape is deployed against migrants and the vibrancy of their bodies after death. This reading leads to a consideration of waste across the border as seen in the fourth section of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, “The Part about the Crimes.” A fictionalized representation of the feminicides in Ciudad Juarez, Bolaño’s narrative shows the reduction of women’s bodies to capitalistic waste. Taken together the two pieces illustrate the dismissal of bodies to waste and wasteful under overlapping immigration and economic policies. Moreover, both pieces show how death in the borderlands is central to American understandings of sovereignty. The result is increasingly militarized environments and solidified borders in the form of physical structures, cultural attitudes, and policy.

The Trump Wall: a Cultural Wall and a Cultural War

This essay decodes a Wall-DNA in American culture with an examination of two shaping moments in history, namely the Founding Fathers and the Mexican-American War. It argues that the Trump Wall, instead of protecting, endangers American values and opportunities; instead of uniting the nation, divides it and ignites cultural wars. The Trump Wall portends fear, bigotry, distrust, intolerance and disconnection; it is the Trump War. Therefore, this border construction is more of a mental construct than a physical one, especially when it involves a cultural re-landscaping and boundary shifting between the US and Mexico and within the two nations. The essay also challenges a one-dimensional and static view on American values, and calls for a 21st century sophistication for a culturally nuanced definition of what America means, and a 21st century agility to cross back and forth any walls without sparking a war.

#eatthatwall

#eatthatwall is an in-progress performance-installation, presented first at Rhizome DC (a DIY experimental art space in Takoma Park, Washington, DC) on April 23, 2017. The project invited gallery participants to assist in the construction and eating of an edible wall made with approximately 1,200 mini cooked rice bricks set with refried bean mortar. The wall served as an imaginary, fabulist structure to separate a currently un-bordered area between Laredo in Texas and Nuevo Laredo in Tamaulipas, Mexico, or anywhere else this hypothetical border might arbitrarily fit. The performance score following the introduction to the project is a document of the process of making: from initial concepts, to the invitation to build/mimic, to a contemplation of how we digest the events and emotions leading to the wall, and to its eventual end.

No Pestilence at the Border

In this poem, I explore what various politicians have stated about immigrants using pest metaphors while interweaving pest control discourses. A pest is an animal that is “out of place.” Immigrants, too, are often “out of place” or “uprooted” or in between places. They live between the world in which they are from and the world in which they inhabit presently, never fully fitting into either world. As there is a multiplicity of immigrants who choose to cross the border from Mexico, there is also a multiplicity of pests who cross different kinds of borders and boundaries. Pests and immigrants are liminal beings, making some people uneasy. My intention here is not to universalize the figure of the immigrant nor the figure of the pest, but instead to explore the complications of immigration-pest discourse in US political cultures.

Death on the US-Mexico Border: Performance, Immigration Politics, and José Casas’s 14

Jimmy Noriega looks to theatrical performance as a method for engaging the subject of “illegal” immigration and, in particular, the death of undocumented migrants. He argues that theatre can provide an avenue by which to generate both a private and public discourse that allows for a more nuanced and fair treatment of migrant death, which is especially significant in comparison to the representations offered by the typical media coverage. Rather than focus on several texts, this essay analyzes one play—14 by José Casas (2003)—and the ways it engages with mass migrant death and the myriad of responses to it.