At Elaine Mokhtefi’s residence along the Hudson in New York City. September 10, 2019.

This assembled interview centers both Elaine Mokhtefi and Le premier festival culturel panafricain d’Alger 1969 (PANAF), a festival which she organized and attended as a part of the Algerian Ministry of Information, and which was an exemplary instance of the power of performance at the nexus of political ideology, activist history, and the subsequent nostalgia for that era of liberation. The assembed interview is equally an attempt to overcome my distant relationship to each, reflecting on the potential of oral histories to open up new pathways through the past. This history—of entangled international relations negotiated under the guise of a festive performance, a complicated trajectory of global politics which culminated in a remarkable event of celebration and solidarity—remains understudied, a footnote to more “political” concerns of Third World agendas, decolonial re-orderings, and capitalist critiques. Yet through the conviction of Mokhtefi’s testimony here, interwoven with my own searching tendrils of archival detail, we can see that this festival was not a superficial exaltation in extravagance, but a pivotal moment in foreign affairs. More importantly, through her personal history, we can trace the central role that women played in these politics, if often unacknowledged. Edited in 2020, this assembled interview also counters the pejorative label of non-essential labor applied to most cultural activities during the contemporary pandemic response to COVID-19.

Elaine Mokhtefi, born 1928 in New York of Jewish heritage, is an author, painter, and activist who, after leaving the United States in 1951 for France, began a career as a translator and journalist and returned to New York to work for the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) from 1960 to 1962. In these years, she traveled to international meetings, developed a strong antiwar and anti-colonial stance, and participated in the 1960 World Assembly of Youth in Accra, where she met and began a collaboration with Frantz Fanon and Mohamed Sahnoun. The reality of the Algerian revolution informed her understanding of international relations; she lived in Algiers from 1962 to 1974, during which time she continued her worked with the FLN and other revolutionaries, including the Black Panther Party. Throughout her career, she would encounter more resistance leaders, including Eldridge Cleaver, Stokely Carmichael, Fidel Castro, Houari Boumédiène, and Ahmed Ben Bella. Moving fluidly between these international spaces, her identity complicated boundaries of race, religion, nationality, and gender commonly associated with lead figures of the time, including the aforementioned individuals. In the archive, her life opens an alternative perspective to the dominantly male and state-sanctioned records of the moment.

While PANAF occurred on the precipice of a total African independence and can be characterized as riding this euphoric wake of liberation, it is perhaps more aptly situated as an attempt towards Africa’s inclusion in global history specific to Algerian interest. Through the multinational and multiracial participation of the festival, I argue that PANAF’s configuration of pan-Africanism was less exclusively of Black diaspora arts such as at previous festivals, but of the Third World, between capitalism and communism, and all in opposition to European colonialism and Western imperialism. Internationally, 1969 was the height of the nonaligned movement, the emergence of the Third World in the midst of the power play of the Cold War. This movement worked against structuralist logic and bipolar rhetoric of difference to counter East-West dualisms by positing another possibility: the Third World. When the Cold War ended in 1991 and global capitalism and liberalism triumphed internationally, the socialist projects of pan-Africanism and the Third World faded. Yet PANAF occurred within this window of potentiality, when the possibility of global reordering still seemed obtainable.

Animating the space between individual and collective history, memory and utopia, this assembled interview centers not the festival as object of analysis but Mokhtefi’s subjectivity, and highlights historical intersubjectivity as the dialogue between Mokhtefi and me remains foregrounded.1 Luisa Passerini, with her critical work on gender theory and the utopia of the 1968 social movements, invisibly guides my practice of research, listening, and communication, challenging normative relationships between subjectivity and power. By keeping Mokhtefi’s words intact and thus highlighting my method, I mark the “sense of fluidity, of unfinishedness, of an inexhaustible work in progress,” and accentuate my “experience of encounter” alongside a more traditional reconstruction.2 With this in mind, I supplement the original transcript between Mokhtefi and me with my own archival research, in order to emphasize where and how knowledge was coproduced rather than co-opted. It is a simultaneous dive into the cultural and political intersections of a performance of the past, exploring the intertextual relationship between history and memory. The goal is to entangle, not conflate, her memory with my research, inserting but not integrating our parallel trains of thought. Rather than relegating the festival to the past, this form extends its narrative life well into the twenty-first century, tracing its reverberations out from Mokhtefi’s own memory, reminding myself and the future reader that oral histories tell less about events than their meaning.3 What follows dually reflects my historical interest in the politics of the festival as rekindled by the nostalgia of its fiftieth anniversary enthusiasm and Mokhtefi’s experience of its original performance, understanding that both are shaped by the context of the present moment.

That Tuesday afternoon was the first and only time I met Mokhtefi, though having read her memoir in advance I felt as though we had already met. Yet in that text I had been surprised by how few words she dedicated to the festival in the memoir given its centrality to my own scholarly work; I wanted her to elaborate those few pages, my desires admittedly contaminating her recount. I offered her hydrangeas upon ringing the doorbell; she offered me sweets in the kitchen, an apt metaphor of the exchange of perishable memories and consumed histories to come in our own “indeterminate encounter” with the past.4 Before leaving, she would write in the jacket cover of my book: For whom the past is always present. There has never been a more perfect epigraph to begin my reading then and mark your reading now.

An Overture

Mokhtefi: It was a unique experience; amazing and unexpected. They attempted to redo it many years later, but nothing like it was at the beginning. Not even the organizers could imagine what it was going to become. It was reality; it really took place.

“It” was Le premier festival culturel panafricain d’Alger 1969, since abbreviated as PANAF. On July 21, 1969, precisely fifty summers prior to my interview, the city of Algiers filled with festivity as the organized chaos of celebration flooded the capitol. Streets were barricaded from traffic in preparation for a grand parade. As spectator Nathan Hare documented, “on the first night of the Festival, its streets were filled with multi-colored balloons floating against the background of a gaily illuminated sky, as twenty African countries came through in a parade. Guinea was the most applauded, but there was fellowship and entertainment for all, from Guinean ballet to restrained dancing in the streets.”5 Mokhtefi suggested even more. Nation after nation, each carrying a hand-painted banner with their country’s name, paraded through the avenues of old Algiers to the applause and whistles of crowds who lined the streets. Dancers and drummers energized these arteries, filling the space with kinetic bodies and percussive sounds. This parade opened PANAF. In totally, thirty-one state delegations and six liberation movements officially gathered for ten days along the northern shore of Africa to celebrate an African identity in the Arab city known as the “Mecca of Revolutions.”6

PANAF occurred in the wake of decoloniality. It showed “Africa on the verge of finding at last whatever else is needed.”7 In the euphoric triumph of liberation, “pan-Africanism, as well as Négritude, may with some justice be termed a utopian ideal.”8 Indeed, it is impossible to overlook the euphoric affect which surrounded the festival, both then and now. But rather than to be critical of this utopia in light of the harsher reality and ultimate “failure” of the postcolonial moment, what can be learned from this unique performance of positive energy?9 What lies beneath the nostalgic celebration of the event? Of equal importance, who contributed to its realization and success? To respond, this interview, which elaborates the history and context of the festival through the memory of Elaine Mokhtefi, crosses media and method, using film, newspapers, photographs, and memoirs; oral history, archival research, and theory. Together, we first address the structure of the event, the recollections of it, and finally allow for contemporary resonances, serendipity and all.

The festival’s history admittedly already lives in existing literature, but often as periphery to larger concerns: a trajectory of aesthetic terms from the Négritude movement to Black Power, a chronology of African festivals, or otherwise glossed for the sake of another argument of diasporic solidarities and transnationalism.10 Few center the festival within an Algerian national history, and fewer, if any, emphasize the predominant role of women in its production, performance, and attendance. To my knowledge, there is not a book singularly devoted to this event, and even Mokhtefi’s own memoir offers it only a few pages. For texts that do center the festival, many were produced at the time and thus cannot contextualize its significance within a larger political history as allowed by the retrospection of oral histories, and do not attempt to gesture to contemporary relevance.11 By accentuating how the festival was deeply rooted in Algerian politics, I argue for the significance outside of an aesthetic or cultural inheritance linked to pan-Africanist ideals. Moreover, by centering Mokhtefi—her testimony itself an invaluable contribution to our understanding of this political moment as she was privy to both American and Algerian leaders—I challenge the primary narrative in which patriarchal authority dominates historical representation. If exemplary, Mokhtefi and the festival alike suggest an alternative narrative of women’s rights in the decolonial era with implications for the political value of culture in the twenty-first century.

Act I: Reconstructing the Structure of PANAF

Kimmel: Was PANAF organized by the Organization for African Unity and then hosted by Algeria? Or did the initiative come from the state of Algeria?

Mokhtefi: It was a decision of the OAU. It was the OAU banner. But who organized it? Algeria. Who paid for it? Algeria. I don’t know whose idea it was, but maybe it was Algeria’s.

The festival was conceived well before its realization in 1969. The intricate labors required to produce such an elaborate event—including the cooperation of international relations, negotiated politics, and economic networks—reveal its logistical accomplishment. PANAF arrived on the heels of Kwame Nkrumah’s influential 1963 text Africa Must Unite and less than five years after the founding of the Organization l’union africaine (then the OAU, now the African Union). Established in 1963 in Addis Ababa, the OAU endeavored to “promote understanding among our peoples and cooperation among our states in response to the aspirations of our peoples for brother-hood and solidarity, in a larger unity transcending ethnic and national differences” including “educational and cultural cooperation”.12 In 1964, at its first session in Kinshasa, the Committee on Education and Culture adopted a resolution to develop cultural activities, such as artistic collaboration via the exchange of artists, expositions, and festivals. At the second convening in Lagos 1966, a resolution was adopted which recommended the organization of “Festivals d’art dramatique et d’artisant africains.” By September 11, 1967 in Kinshasa, the kernel of PANAF was planted.13

But as Mokhtefi suggested, Algeria was the driving force, first offering to host the event and then acting as the primary curator and administer. One year later, at the next annual meeting of the OAU, the dates and location of PANAF were confirmed for July 21 to August 1, 1969 in Algiers, a symbolic expression of solidarity between Algeria and the OAU.14 Houari Boumédiène was a key interlocuter. In 1969, Boumédiène served simultaneously as president of Algeria, chairman of the Revolutionary Council, president of the Counsel of Ministries, minister of national defense, president of the OAU, and eventually the fourth secretary general of the Non-Aligned Movement. His public support and endorsement of the festival lent credibility and authority, as well as clear political leanings, to its realization and positioned PANAF as an event linking all of these concerns.

The history of PANAF reached beyond the founding of the OAU, and must be understood within the specific historical context of Algeria, too. In October 1962, a recently liberated Algeria entered the UN under the leadership of Ahmed Ben Bella. But stability for the new nation was yet to be established, as the Algeria inherited from France was broken, its infrastructure, economy, and market devastated by the Algerian War of Independence, exasperated by the scorched earth policy of the French Organisation de l’armée secrète. In 1965, Ben Bella was overthrown by Boumédiène, both of whom governed via the symbolic value of a one-party state and militant force. Boumédiène would rule until his death in 1978, throughout which he promoted socialist ideals and unity of the Non-Aligned movement. This timeline suggests that, at PANAF, Algeria was still establishing a new national culture which embraced is revolutionary and decolonial status, propagated by the Arabization movement/moment.

Financially, Algeria backed the majority of the festival, with additional monetary support from the OAU and UNESCO. Originally estimated to cost four million dinars—then, nearly four million US dollars—the final invoice was estimated at just under five million US dollars. Algeria provided nearly three million of this total. The festival noted that UNESCO provided ten thousand dollars, though this evidence is not replicated in UNESCO’s own budget.15 Mériem Khellas has astutely linked the robust Algerian financial investment in the festival to the status of the state’s fiscal standing, which was largely rooted in hydrocarbon extraction and petrol production. In advance of the festival, from 1963 to 1968, Algeria’s petroleum revenue increased six hundred percent, attributed largely to the monopoly company Sonatrach, founded in 1964. The increase of the petroleum revenue paralleled the budgetary growth of the Algerian Ministry of Information and Culture, which administered the festival. With its international economy, this new industry also increased the flow of foreign presence in Algiers, preparing the city for the international texture of the festival.

Kimmel: Were women and children more prevalent at the festival than typical of Algiers of the time?

Mokhtefi: Oh, yes. Women, even veiled women, and children came out. You could not hold them back. It was uncommon for then, very uncommon. They were not used to going out like that. I suppose that most of them had never been to a theater performance in their lives. Here in the street were people performing, and they were there. They were there until two, three, four o’clock in the morning. They were out there, the women. Unbelievable. The festival was amazing on several dimensions, you see. It was amazing because it brought together all those artists from all over Africa from such different cultures and different backgrounds. It was also amazing for what it did for the people of Algiers.

Algeria’s postcolonial nationality was formally articulated via the 1963 Code de la nationalité, granting citizenship only to Muslims.16 Simultaneously, many Algerians lost French nationality as a result of statut civil du droit local originaires d’Algérie. This code also formalized religious and patriarchal hierarchies, as it defined an Algerian as a Muslim person whose father and father’s father were also born in Algeria.17 In 1970, a year after PANAF, this religious requirement was removed, but citizenship remained a patriarchal inheritance.18 Thus, the strong presence of women in the arts at PANAF—Miriam Makeba first and foremost but famously also Nina Simone, Assia Djebar, and Elaine Mokhtefi alongside countless others—accentuated a gender divide between arts and politics. The radical revolution leaders and heads of state celebrated at the time were all men.

Thus as a young country still establishing is postcolonial identity (if not economy too), Algeria had specific motivation in volunteering as the host of the festival. As Kathleen Cleaver—an American Black Panther in exile in Algiers at the time of the festival—commented, “A part of Boumédiène’s strategy was to promote Algerian leadership at an international level, and one step in his program to bring Algeria into the leadership of Africa, the Arab world, and non-aligned nations, was to host the first Pan-African Cultural Festival.”19 From the beginning of this choice location, pan-African and pan-Arab ideologies were crossed in the festival’s choreography that challenged gendered norms.

Kimmel: Were you a part of the organizers?

Mokhtefi: Yes, I was a member; I worked in the office. It was organized by the Ministry of Information, as led by Mohammed Benyahia. He brought me into the ministry for the purpose of organizing the conference. We were old friends. He had been part of the Algerian delegations that came to the US when I was working in the Algerian office for the purpose of influencing the United Nations.

During those delegations, they would remain in New York all throughout the debates. That was often well over a month. He and I became friends, and when the decision was taken that he should be the Algerian organizer of PANAF, he asked me to come work in his ministry. I was one of the rare people in Algeria who spoke English at the time. Also, he had found me efficient during the debates at the United Nations. He knew that he could count on me. So, we organized the festival. I was part of the group that organized it.

Kimmel: In terms of the audience at the festival, was it mainly Algerians, or mainly tourists from Europe?

Mokhtefi: It was mainly local people. They said there were sixty-thousand people. Of course, there were a lot of people who came from abroad. There were a lot of people from the US, even from Brazil, France, the Middle East. They came from all over. It was a unique experience, so the people came. A lot of African-Americans came. When I say a lot, it is all relative, right?

The reach of PANAF extended beyond the continent. For example, Lionnel Enrique, associated with the théâtre Cubain troupe Los-Papines, “stated he was very interested in this festival which could revalorize the African culture,” and spoke more generally of the parallels and influence of African culture on Cuba.20 The exchange went in both directions; not only did PANAF attract international and intercontinental attention, but PANAF also exported their ideas abroad. Prior to the festival, several writers, including Alioune Diop, traveled as delegates to France to inform Paris of the forthcoming festival, and “the need for Africans to regain full control of their culture,” an understandable counter to the French mission civilisatrice.21

As other scholars have noted, the festival followed the 1966 World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar as headed by Léopold Sédar Senghor, at which Algeria was not officially present. The event at Dakar was considered a celebration of and for the Négritude movement, rather than pan-Africanism, the former an ideology present but not prominent at PANAF. However, I do not mean to reify a binary opposition between these festivals, as Dominique Malaquais and Cédric Vincent have properly warned against, or replicate existing scholarship on the aesthetic trajectories between the two.22 Rather, I simply stress that while PANAF came after the festival of Dakar and must be read as an intentional evolution, its motivation was related, but sharply distinct, not least due to the prominent role that Algeria played in the latter. For example, Negro Digest’s Hoyt Fuller, and audience of both PANAF and the Dakar Festival in 1966, “seemed particularly struck by the contrast in the type of black Americans at the two festivals. Dakar had collected the most well-known artists and entertainers, the Duke Ellington’s and others; Algiers had attracted the new breed young militant where those of face, those on the rise, or those yet to begin the making of their names.”23 As such, PANAF was a rally call for an international movement, more so than a reflection on cultural inheritance and shared aesthetics. Contextualized within Algeria’s history, it was a strategic political move meant to serve the nation as much, if not more, than the continent and diaspora.

Kimmel: Was there much attendance by sub-Saharan Africa?

Mokhtefi: As participants, yes, but not so much as an audience. But they sent large delegations of artists, dancers, and singers. Government ministers, especially ministers of cultural affairs, came, and there was a symposium alongside the outdoor events. The symposium was in a closed center on cultural affairs. Resolutions were passed, and speeches were made, and so on. That was much less exciting than what was happening in the streets of the city and in the theaters at night . . .

Spatio-politics abounded at the festival, illuminating, intensifying, and at times crossing boundaries between performance and visual culture, state and citizen, local and foreign, modern and traditional. The city committed to material upgrades in preparation for the festival, including illuminating the streets with new cables for lighting,[xxii] expanding the sanitation infrastructure, as well as constructing several temporary hospitals, lodgings, and infirmaries.24 Live theatres and cinemas were equipped with the latest technology to accommodate the technical needs of the artists. If for the sake of a pan-African festival, Algeria alone benefited from the lasting material investment. The investment in revitalizing the infrastructure of the city paralleled efforts matched only by other internationally acclaimed events such as the World Cup or the Olympics, whose opening ceremonies also mimic the festival’s parade of nations. But while the Olympics facilitates a convergence of many nations to compete against one another, PANAF converged differing nations under the common guide of pan-Africanism for a common cause of renewing the strength of the “African personality”—both within and outside of the continent.25 Competition was thus replaced by cultural performance, winning and losing no longer the spectacle conjoining international concerns.

Clearly politics and culture were entangled throughout the festival, if spatially divided. The symposium, during which the Pan-African Cultural Manifesto was drafted, was held at the Palace of Nations and included official delegates from participating nations as well as an informal Russian delegation and representatives from the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, Al Fat’h.26 Culture was defined at PANAF as “the essential cement of every social group, its primary means of intercommunication and of coming to grips with the outside world: it is its soul, its materialization and its capacity for change”.27 The manifesto concluded with forty recommendations and policy proposals for the sustainable development of cultural activity in Africa. In addition to this cultural arm, the symposium devoted time to science and technology, particularly of atomic energy, nuclear development and agriculture, as attended by over one hundred twenty delegates and twenty countries.28

Yet the separate resonances of the symposium and the opening parade exemplified spatial and political divisions, in spite of claims that culture and politics were equal. The use of the public street during the parade route for the artistic delegates versus the private space of the palace for the political elite highlights the limits of the festival as a cultural event for all. The festival thus revealed the entangled, messy politics of culture, as well as the culture of politics.

Kimmel: Did the Panthers participate or just attend as audience members?

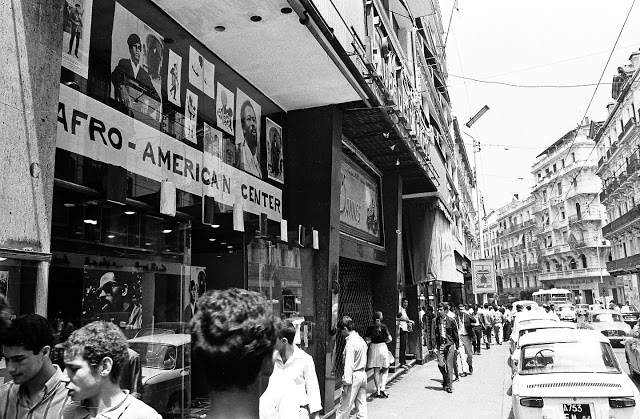

Mokhtefi: They were given a storefront, distributed leaflets and posters, gave talks, and put on films. To that extent, yes, they did partake in the festival. Several of the Panther leaders came from the US with loads of literature and paraphernalia. Eldridge and Kathleen were already there. There was Emory Douglas, the Cultural Minister, David Hilliard, the Executive Director and Raymond Hewitt, the Education Minister. They were the Panthers that were officially there.

They stayed for the whole length of the festival. Their office was in this storefront on the Rue Didouche Mourad, one of the two major streets of Algiers. The Algerian government provided the storefront which had been empty. I don’t know who owns it or who owned it; the Algerian government provided it. They set Eldridge and Kathleen—and some of the others, I think David, Emory and Hewitt—up in a hotel, one of the two best hotels in Algiers. They gave the Panthers royal treatment. They were very happy to see them.

So the Panthers were right in the center of the city. It was packed all the time. And outside there were kids and grown-ups always hanging around. I’ll show you a picture.

The Black Panthers arrived in Algiers in June of 1969, in serendipitous convergence with PANAF alongside African heads of state. Author of Soul on Fire and Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, facing attempted murder charges in the US, fled to Cuba and then sought exile in Algeria, a country which, since independence, had garnered a reputation as a sanctuary for revolutionaries. Stokely Carmichael had previously spent time there in 1967. More members of the Black Panther party would follow and become active participants at the festival with a dedicated space, the Afro-American Cultural Center, or more informally the “Panthers’ Lair.” This popular storefront was frequented more by young Algerians than Black Americans, forging solidarity around ideological lines of liberation efforts, rather than racial or national affiliation.29 Mokhtefi connected with the Panthers, forging personal and professional connections with Cleaver, at once noting his charisma but acknowledging his calculated edge. She would be instrumental in founding the international sector of this movement.

The presence of the Panthers in Algeria encourages a parallel reading of the simultaneous histories across the distant geographies of Oakland and Algiers, recognizing both cities as specifically multiethnic and multiracial sites of revolutionary activism.30 Stokely Carmichael, later Kwame Ture, served as a pivotal interlocuter. An American civil rights activist and global pan-Africanist, he was a leader of the Black Panther party, Black Power founder, affiliate of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and leader of the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party, who would attend PANAF and seek refuge in Algiers. In 1969, he married Miriam Makeba, a renowned vocalist from South Africa and performer at PANAF. He worked for and alongside both Ahmed Sékou Touré and Kwame Nkrumah, whose names he later chose to share. His second book, Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism, speaks to these ideological entanglements from his individual vantage.

PANAF also occurred in the height of the American Black Arts Movement, a cultural-activist movement of Black pride which spanned the 1960s and 1970s. This movement followed the Harlem Renaissance, and critically responded to the civil rights movements in the US in a manner that, in many ways, echoed the Negritude to pan-African debate. Founded by Amiri Baraka, the Black Arts Movement is associated with values of identity, expression, and liberation. Prominent artists of the movement include Hoyt Fuller, Nathan Hare, and Archie Shepp, all who were present at Algiers in 1969. African American culture more broadly conceived experienced a reciprocity of exchange, as African diaspora outside of the continent returned. As Shepp professed during a festival performance, “Jazz is Black Power. Jazz is African Power,” linking the two edifying revolutions across the transatlantic in cultural solidarity.31 Much of the history of PANAF was recorded by Hare in the first issue of The Black Scholar, an American journal of Black studies and research. Hare founded the first Black Studies program in the US at San Francisco State University in 1968, following the strikes the Black Student Union and the Third World Liberation Front. Many universities in the US and worldwide would follow suit. His interconnected history, like that of Mokhtefi’s, suggests the need to expand the reading of PANAF from a continental concern to a broader moment of internationalism.

By citing these individuals, I highlight a few of the cultural and political trajectories that this festival strategically intersected, an American front notwithstanding. However, it’s necessary to remind ourselves that the plethora of identities present at PANAF did not imply harmony. As Hare wrote, “Algerian leaders today . . . lambasted the ultra-devotion of many black intellectuals to jazz music and black art and other forms of ‘folkloric prestige’.”32 Rather, the invitation to a plurality of cultural forms—indeed the Algerian government funded the Panthers throughout their stay in Algiers, including financing their cultural center—implied a solidarity of being that valued difference, rather than requiring homogeneity, in its collective.

Kimmel: How did you feel being a part of that as an American? Or perhaps you weren’t regarded as an American?

Mokhtefi: Everyone else saw me as an American. I didn’t see myself so much as an American. I felt more like a world citizen. But others saw me as an American. I felt I was doing something. Here was the Vietnam War going on, and the world being divided up between these two superpowers. I had the feeling that I was doing something.

In a moment of civil unrest, as demonstrations sparked protests worldwide including those against Vietnam, PANAF blurred the line between demonstration and festival, as both can be distilled as a public gathering to voice a political opinion. Both were a means of “doing something.” Protestors in 1968 France, including recent Algerian immigrants, noted this intersection, writing above the occupied Odéon Theater: “When the National Assembly becomes a bourgeois theater, all the bourgeois theaters should be turned into national assemblies.”33[xxxii] This graffitied slogan established a proximal precedent for the use of theater, and the theatrical, for political protest. PANAF, as both theatrical and national assemblage, was produced by the Algerian government just one year after of the May 1968 riots in France. French student strikes echoed the student protests in the US, following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., particularly in California. Both of these precursor events brought strikes, riots, and occupations into the global public, an embodied politics of gathering that was restaged at PANAF in a new light.

Act II: Recollections of PANAF – Between History and Memory

Kimmel: What would you say was PANAF’s greatest success? What memory remains with you most from those 10 days?

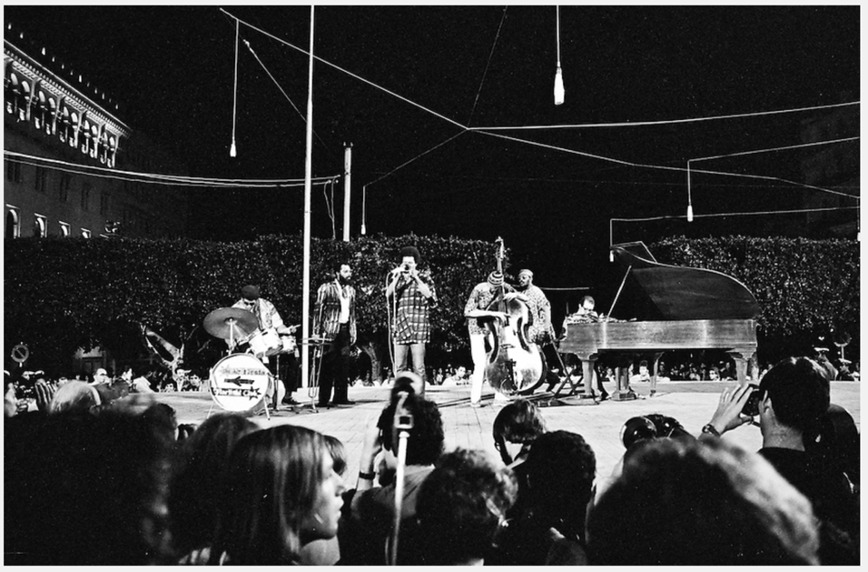

Mokhtefi: [A memory that remains] was meeting Archie Shepp, I suppose. He was amazing. I also became friends with Miriam Makeba. She and I got Nina Simone on stage. Oh, that was very exciting. And then, of course, the Panthers. The Panthers arrived just before the festival. Eldridge Cleaver arrived the end of June, I think it was. They were right on time.

The primary success was that it took place. It was organized by non-professionals. All of Africa was present. Ideas were exchanged. The standard was high, intellectually and artistically. We felt Africa had come into its own and was taking off. Third worldism was being confirmed. Africa would not be the pawn of international capitalism or cold-war rivalries. For me, personally, it was visionary. It was seeing into the future.

An image I found in the archives allowed me to sense that vision, to feel as though I too were in that crowd, if only for a snapshot moment in history:

Mokhtefi was not the only independent American present at PANAF to remember Shepp. Robert Wade, a Californian who found himself in Algiers as a graduate student in 1969, documented the festival through the lens of his camera. He was abroad in Europe and North Africa to avoid the US draft for the Vietnam War. The still photographs remain an important documentation of the event, capturing images of the Archie Shepp band onstage with Touareg singers, children outside of the Afro-American Cultural Center, and the famed streets of the Kasbah. These images offer insight into the pedestrian participation and audience demographics, showcasing a heterogenous public in a spectrum of modern and traditional clothing, during day and night, all occupying the avenues and public squares. Moreover, Wade’s position as separate from government affiliation offers an additional perspective outside of a motivated, nationalist discourse. His presence suggests the far reach of the co-performance of international events and PANAF’s entanglement in many global narratives: of decolonization, post-World War II sentiments, protest movements and civil rights activism, Third World ideology, and Cold War politics. I reflected on the ebullience vibrating within Wade’s archive to Mokhtefi, but she had not seen the collection. So we scrolled through images together on her desktop. I believe the images transported her as much as me— one to a place of memory, the other a place of imagination.

In reviewing the daily Algerian newspaper El Moudjahid, these juxtaposed stories unfolded within its news coverage, and situated the festival within a politically-charged global history. Such ongoing stories include the American success of the Apollo missions, the atrocities of the Vietnam war, the political turbulence of Nasser’s presidency, and the Palestinian conflict. 1969 was also Woodstock and the Stonewall riots; human elation and invention alongside devastation. Native Americans occupied Alcatraz, and students protested US involvement in Vietnam, while people celebrated along Africa’s north shore. At the festival, Eldridge Cleaver recognized the overlapping histories which were unfolding, prioritizing the importance of social and liberation movements: “I don’t see what benefit mankind will have from two astronauts landing on the moon while people are being murdered in Vietnam and suffering from hunger even in the United States.”34 To reflect on the corresponding times of the moon landing and PANAF while China, the US, and the UAE race towards Mars in the present is to suggest an alternative kind of positive energy and expansive vision of the future, a dream of solidarity and hope contra imperialist ambition that continues into the third decade of the twenty-first century.

Kathleen Cleaver repeated the crossings implicit to PANAF:

Southern African freedom fighters and veteran guerillas from Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau at war with the Portuguese joined the colorful delegations arriving from all over the vast continent. Algeria, chosen by the Organization of African Unity to host the festival, insisted that liberation from colonial rule was as central to African unity as music.

She added reference to the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya (1952–1960), Kwame Nkrumah’s rise to power in Ghana (in office 1952–1966), and Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961),emphasizing a collective solidarity around “our battle for self-determination and civil rights.”35 As enthusiasm for the postcolonial moment waned, with economic and political unrest rising in many new nations, 1969 was a pivotal year, itself a festival of events which collectively framed the context in which PANAF was staged such that the greatest success of the event was that “it took place”.

Kimmel: Why do you think the first festival was in 1969? Was there a significance to that year? Or was it simply because enough time had passed after liberation?

Mokhtefi: In 1969, Algeria was a leader of what was called then the Third World. There were several international organizations, like the Non-Aligned countries. OPEC had already been founded. This was a time when we really believed there was a Third World, that there could be. There was the East, there was the West, and there was the Third World. China was part of the Third World then; you wouldn’t say that today. We really thought the Third World would influence the East and the West; that it was somewhere in between. We really thought that. And then each country’s economic problems and political problems came to the fore. Little by little, there was no longer a Third World.

To recall this internationalist potential is central to the PANAF memory. The Third World movement marked its formal origins at the Bandung Conference in 1955, an Afro-Asian gathering of twenty-nine countries representing more than half of the world’s population. Associated political leaders with the Third World Movement include Gamal Nasser, Ho Chi Minh, Kwame Nkrumah, Houari Boumédiène, Julius Nyerere, Patrice Lumumba, Sukarno, Michael Manley, Josip Tito, Jawaharlal Nehru, Thomas Sankara, Muammar Gaddafi, and Amílcar Cabral. Many of these names are explicitly linked to PANAF, but all are encapsulated within its larger logic. The festival allows us to understand the Third World not as spatial orientation or geographic division, but social and epistemological movement, an ideology in performative form. That “it took place”, which is to say required space, is to suggest that itself was not already a territory, a material location, but an idea, a performative, an ephemerality. As similarly argued by Vijay Prashad, “The Third World was not a place. It was a project. During the seemingly interminable battles against colonialism, the peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America dreamed of a new world.”36 More than a decade after Bandung, PANAF extended the afterlife of the conference as it echoed precursory sentiments of the Pan-African Congresses of the early 1900s, finally giving it place.37

As gestured toward by Mokhtefi, 1969 also marked the height of Pan-Arabism, the alliance of Arab states spanning parts of North Africa and the Middle East, especially as allied against Western influence. Pan-Arabism gained traction in the early twentieth century with leaders such as Sharif Hussein ibn Ali, and was revitalized in the 1930s in the Arab peninsula by the Arab Ba’ath Party. It was not until the 1950s, under the leadership of Nasser, that Egypt—and by extension North Africa—would strongly join this movement, evidenced by the United Arab Republic (UAR), a political union between Egypt and Syria from 1958 to 1961 in the aftermath of the Suez crisis.38 Founded in 1960, the Organization for Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) may be seen as an economic extension of Pan-Arabism which extends to the broader geography of the Third World. Not of mere coincidence, Algeria joined OPEC in 1969 as its economy flourished. This timing echoes Khellas’ acknowledgement of the paralleled histories between hydrocarbon extraction, Algerian state revenue, and the generous funding of PANAF, yet another entanglement that places the arts and cultural affairs alongside economic and political expansive.

But by the end of the 1960s, Pan-Arabism had experienced failure including the collapse of the UAR, the fall of the Arab Federation (between Jordan and Iraq), and end of the United Arab States (between Yemen and UAR).39 The Arab defeat in the Six-Day War in 1967 punctuated the decline of this movement, just two years before the festival. Nasser, who died in 1970, was replaced by the nationalist Anwar Sadat, ending a period of Pan-Arab momentum. Thus, the Pan-Arab participation of PANAF—including the emphasis of Arabic as a main language of the festival, its secular nature, attendance by liberation groups such as the PLO, and delegates from Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt—can be read as an attempt to grasp onto the lingering possibility of Pan-Arabism on the African continent. In many areas, Pan-Arabism would be replaced by nationalist and Islamic ideologies. Algeria was no exception. Once again, Algeria’s own timeline, rather than the festival histories or Pan-African efforts, influenced the reality of PANAF.

By the end of 1969, Algeria faced economic uncertainty as the consolidation of a global market, subsistence economies, exaggerating population growth, and regimes of a single-party state took their toll. Hare recounted that after the opening parade of PANAF, “The next day saw a somewhat different Algiers, and what has been achieved since the revolution, not all of it yet so good. The air of celebration continued, but daylight revealed, in at least one major section, project housing tenements as dilapidated as any in the US. Esso service stations appeared, and Shell, and Hertz, and Pepsi Cola (and company); and the French colonialists slipping back in predatory droves.”40 By returning to PANAF, I do not want to paint a false utopia. Part of the festival was a facade over the existing political and economic weaknesses. It is important, nevertheless, to recover a hope in the archive not yet soiled by a harsher reality of totalitarianism or other cynicism.

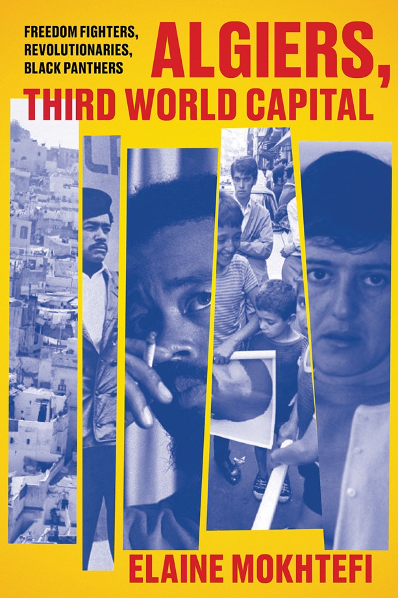

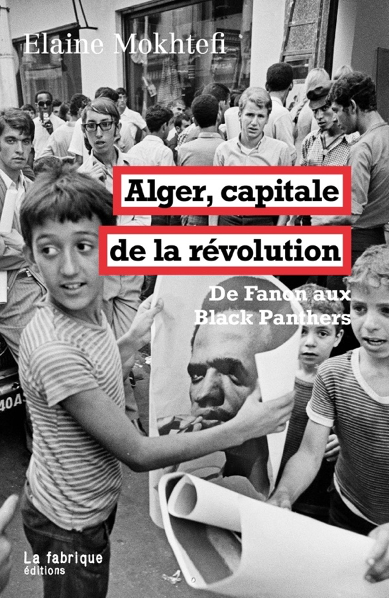

(At this moment, Mokhtefi went to her kitchen desk to retrieve a copy of her book, Algiers: Third World Capital—Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers, and its French translation.)

Mokhtefi: This is the French language book. It’s given a different title, but it is the same text. They changed the title to Alger, capitale de la révolution: De Fanon aux Black Panthers.

Algiers’ reputation as the “Mecca of Revolutions,” alluded to in Mokhtefi’s memoir, harkens back to Amílcar Cabral, a revolutionist and Pan-Africanist from Guinea-Bissau and leader of the PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde), which he founded and led from 1956 until his assassination in 1973. At the festival, he boldly prophesied, “Pick up a pen and take note: the Muslims make the pilgrimage to Mecca, the Christians to the Vatican and the national liberation movements to Algiers!”41 Not only did his language conjure revolutionary values, but it also conjured literal mobilization, asking the African public to cross geographical and geopolitical terrain in order to animate the festival. His language also evoked a secular stance of anticoloniality by rescripting religious intonations for his liberationist cause. This religious analogy, which was not without its problematics, was echoed by Kathleen Cleaver: “Thus, visiting Algiers became almost a kind of pilgrimage for black revolutionaries in 1969.”42 Here the call to pick up a pen rather than a pistol suggested an alternative to physical violence, complementing a Fanonian logic which had swept the region as the festival presented both.

Furthermore, Frantz Fanon was present in Algiers in the mid-1950s, and was so affected that he chose to be buried in Algeria, in spite of his foreign nationality. Malcolm X (significantly a founding member of the OAU) and Che Guevara both visited in 1964, and Eldridge Cleaver took exile in Algiers (after fleeing to Cuba) in 1969.43 Nelson Mandela too affirmed the affectation of the revolutionary spirit in Algeria in his autobiography. Mandela wrote, “This situation in Algeria was the closet model to our own, in that the rebels faced a large white settler community that ruled indigenous majority.”44 This list of famed revolutionists constitutes a small sample of those who crossed through Algiers’ streets attesting to the origins of the name that motivated Mokhtefi’s title. This epithet of the city was re-popularized, or at least re-stabilized in the archive, by Jeffrey James Byrne’s 2016 monograph, Mecca of Revolution: Algeria, Decolonization, and the Third World Order.45

I had brought a copy of Moktefi’s Algiers, Third World Capital with me, but she made a point to show me the French translation:

Kimmel: Did you translate the text or have someone translate it for you?

Mokhtefi: The publisher changed it. It was last year, when they got the French text, that they decided they would change the title. They thought this was a better title in French. This was before the demonstrations started in Algeria.

The insertion of Fanon’s name into the French title is far from neutral, and points to the mutability of the archive even in linguistic form. The long resistance movement was led by the FLN, an opposition party which succeeded the Algerian People’s Party. Famously, Fanon was a leading theorist of liberation, and his justification of violence influenced the party and its militant wing, the National Liberation Army. Fanon’s writings were regularly published in El Moudjahid, the FLN party paper which also covered PANAF, linking the events and ideologies through a shared archive.46 As he published, Algeria also found an international voice in literature and theory with the growing attention to francophone authors such as Albert Camus, Jacques Derrida, Assia Djebar, and Malek Alloula, amongst others. Specifically, 1961 saw the French publication of Fanon’s Les Damnés de la Terre, which ideologically influenced the revolutionary call of pan-Africanism across the globe. Two years later, the text was circulated in English for an even broader public.

Situated in such close proximity to this moment of intellectual production and resistance (perhaps better phrased as intellectual production as resistance), the festival assumed the responsibility, intentionally or not, of allowing these political ideologies to come into discourse with one another, facilitated by the peaceful guise of culture. Indeed, Djebar and Alloula would coauthor a play for PANAF. Both the streets of Algiers and the spread of the paper were spaces for such negotiation throughout the festival.

Mokhtefi: In France, the book has had tremendous success, much more than here. It’s important to understand that the Algerian War is a dark spot on French history. So they skip over it. I’m really surprised, really surprised, that this book is taking off. I’m not an intellectual, I’m not a university professor, I have not even graduated from college. But I was there and the book has taken off. It really has. I’m just totally surprised, amazed, and happy.

France had not officially recognized the use of torture during the Algerian War for Independence until Macron issued a public and official apology in 2018. Until 2005, French schools were required to teach positive aspects of colonialism: an intentional mis-memory, an attempt to disavow history into the past. From the 2005 dissent, a learning module was added on the memories of the Algerian War.47 As the popularity of Mokhtefi’s memoir indicates, PANAF allows for an accessible, if tangential, discussion of this history as it addresses the residual legacy of colonialism without implicating a singular government. Even as Mokhtefi downplayed her role—be it personal humility or structural gender subordination—her lasting impact on French-Algerian history is self-evident.

Act III: Remembering Now

Kimmel: I know that the festival was repeated in 2009 as a fortieth anniversary performance, if with less pomp and circumstance. Why do you think it wasn’t as successful in recent times?

Mokhtefi: Yes, there was a repeat performance. I wasn’t there, though Kathleen Cleaver was. She had no basis of comparison though, because although she was in Algeria during the PANAF, she was having a baby at the time. What she told me was it was pretty good, but from what I have read, it had nothing of the strength, of the participation, of the surprise and enjoyment of the first festival. It’s like Woodstock; you can’t repeat those things.

I saw recently a film has come out done by an Algerian, which you can get on YouTube. I’ll show you afterwards. It’s a bit about the festival. Also, there’s a short film on the festival, not the Klein film. Klein’s film is very visible. It’s very visible for people to study, but not as an entertainment—for that, it was a flop. But there is also a short film on the festival. Have you seen the short film? In fact, Archie and I are in it. I’ll show you. And then there’s this film that just recently came out, maybe last year or maybe or the beginning of this year. It’s very recent.

As Mokhtefi noted, the primary footage of this festival comes from William Klein’s documentary film, The Pan-African Festival of Algiers, which was commissioned and funded by Algerian officials to promote its foreign policy “in solidarity with the liberation movements” across all of the African continent, not just the north, as well as Cuba and Vietnam.48 Klein’s documentary footage of PANAF provides unparalleled video access to the festival, including on and off-stage moments from several performances, the opening parade, highlights from the symposium, and private conversations in dressing rooms.49 A 2010 republication by Arte Editions includes a multimedia handout, with contemporary reflections written by Klein, Kathleen Cleaver, and acclaimed Algerian author Rachid Boudjedra, among other voices, and has been screened with renewed vigor in recent years across Paris and France as the festival received attention on account of the anniversary. These reflections collectively gesture beyond the festival, to events such as Woodstock, leaders such as Nelson Mandela, and violences elsewhere, including Vietnam, allowing the reader to understand how a variety of participants in the festival contextualized PANAF amidst the specific historical moment.

This republication opens toward an establishment of nostalgia which so often surrounds moments of celebration. In the fiftieth anniversary of PANAF and 1969, during which I conducted this interview, there was heightened attention to PANAF more broadly, including a conference at Johns Hopkins University, “Paris/Algiers 1969: Declarations of Freedom by the Black American Avant-Garde,” at which both Elaine Mokhtefi and Archie Shepp were present. Much of the (still limited) archival work surrounding PANAF, such as Khellas’ text, was completed in 2009 in its fortieth anniversary performance. At risk of teetering into the speculative, what is the significance of the half-century, and why does it raise a collective nostalgia? How would this interview be different it if it was conducted in 2018 or 2020, close to but not during the height of PANAF’s remembrance? In short, why does it take an anniversary to remember?

Kimmel: Do you think you’ll go back to Algeria?

Mokhtefi: I did go back. I went back for about three weeks last year. And I’m going back again; this time now I’m invited. Every year they have what’s called the Salon international du livre d’Alger. It is a book fair, an enormous book fair. So I have been invited. After being banned. In fact, yesterday, we agreed on what day I would be arriving, what day I would be speaking, and so on. Unbelievable. I’ll go back towards the end of October. It’s amazing.

I am lucky, I can say, because my husband was Algerian. So they finally gave me a visa. And once they gave me the visa, then I can return. For forty-four years I didn’t go; I wasn’t able to go.

There is an uncanny repetition to Mokhtefi’s experience of having been deported from Algeria in 1974 and banned from return under political circumstances, and my own experience as an American, female researcher—if our positions and expertise are strikingly different. In 2019, after receiving a generous research grant, my own visa application for Algeria was denied. I was once again reminded of my own exteriority to this history, dislocated in both time and space. I was reminded of the further impossibility of ever fully crossing that fissure, in spite of the memory and memorabilia of the festival which exist in the archive, interviews, and images. This gap continues to trouble me today, and underscores my desire to keep separate Mokhtefi’s memory from my research in the printing of this interview. Sometimes we aren’t meant to (time) travel.

Kimmel: I’m curious about your recent experience there, particularly if you felt things had changed?

Mokhtefi: It’s changed so much that I didn’t recognize it. The city of Algiers, everything has changed. The country, everything. Everything changed. When I went to live there in 1962, there were nine million Algerians. Today there are over forty million. They are well on their way to fifty million. The growth has changed the country considerably. We were able to be idealistic. Our first preoccupations, our first concerns, were not about economics. They were about freedom and justice, whereas now the first is economics with political problems often take the backseat. It’s a very different world. At some point Algeria and Third World did not exist anymore. At some point, Algeria was concerned with its economic problems and the political problems that came out of those economic problems. They had a ten-year civil war. The country has changed. Now, since the February 22, since I was there at the end of 2018, there are demonstrations. Practically continual demonstrations every Friday and every Tuesday: every Friday everyone comes out and demonstrates. Every Tuesday, the students. What are they demonstrating for? They’re demonstrating for more justice. It’s a very difficult situation. The army has held off up till now. Let’s hope that the army continues to hold off.

Writing from the interstitial moment again allows us to document hope. On February 22, 2019, public demonstrations began in Algeria to protest the high levels of unemployment, corruption, and austere authority, first calling for then-president Abdelaziz Bouteflika to not pursue a fifth term and then calling for all affiliated political members and militant leaders to also step down. Bouteflika had been in power since 1999, but had not been seen in public since a stroke in 2013. Many sites of these protests were previously host to the festival, echoed scenes of bodies in public space for political visibility.

In April 2019, Bouteflika resigned as a consequence of continued protest and political unrest, with Abdelkader Bensalah stepping in as interim president. An election, originally scheduled for July was postponed indefinitely due to too few viable candidates.50 Tens of thousands continued to march in opposition. Eventually these street protests movements, known as the Hirak, grew to weekly demonstrations of hundreds of thousands in Algiers and millions across the nation, eventually with solidarity marches worldwide. Arrests proliferated during this time. Yet unlike the Arab Spring and other precedents of revolution and social movements, the Hirak radically disavowed the use of violence.

The final vote was held after my interview with Mokhtefi, in December 2019, between five candidates: former Prime Ministers Abdelmadjid Tebbourne and Ali Benflis, former Culture Minister Azzedine Mihoubi, former Tourism Minister Abdelkader Bengrine and Abdelaziz Belaid, head of the El Mostakbal Movement party.51 On December 12, Abdelmadjid Tebbourne was elected, a close affiliate with the military. After forty-two consecutive weeks of protest, demonstration, and policing, the result did little to calm the nation’s tensions. Protests continued the following day, and the streets remained animated, as if the festival’s energy lived on with new cause.

Kimmel: Do you have nostalgia for that time period? Or is it simply in your past?

Mokhtefi: With my husband being Algerian, we talked about Algeria all the time. We followed all the news out of Algeria. I felt a tremendous nostalgia, and he did too. But he was an army veteran, a Liberation Army veteran. He was also the first president of the National Student Association after independence. He was close to politics. He felt it had become the kind of country that he did not want to live in. We were all continually waiting for the day that things changed, but they just got worse instead of changing for the better. Finally, it was civil war. So now, there seems to be a tremendous wake up, a second revolution. People are out there striving for something better. Enough people are saying, ‘I’m not afraid.’ So maybe it will come off. At least, I feel sure that whatever comes out of all this, it will be better.

There was a desire for justice [at PANAF]. All of these people who came were bursting. They had all known colonialism, all of those countries, all of those liberation movements. They had all known colonialism. And what a difference with freedom. What a difference.

It’s not to say that people who have been through colonialism are not to some extent narrow minded, racist, capitalistic, or imperialistic. But it is to say that they share something very human. I felt that all through that festival, this humanity. And I think all of the African Americans who came also felt it really strongly. All of poets, the writers, and the musicians; they all felt it very strongly. I know that Archie did.

During PANAF, Assia Djebar debuted her first and only play, Rouge l’aube, co-authored with her then-husband Walid Garn. The script ends with the directive, “The collective song stops.”52 Has the song of PANAF stopped singing, too? Can interviews such as this do anything to keep it alive? Or is nostalgia for a joy of the past meant to fade in history, so that new moments of performance, protest, and solidarity can take its place?

The constant entanglement of culture and politics defined the festival as more than entertainment or celebration, lifting the festival out of an exclusively artistic trajectory and certainly above the label of non-essential. Revisited in a time when in-person interviews, let alone multinational festivals, seem the antithesis of commonplace, its performance evidenced not a fear of togetherness and proximity, but an investment in its very possibility. Adding to existing knowledge of the festival, Mokhtefi’s life centers the significant role of women at the time and recenters Algerian national history as critical to the understanding of PANAF. Crystalized as testimony, Mokhtefi’s reflection defined “the terms of the cluster of ideas that lies at the center of this collection” and, paired with archival research, underscored an interwoven history coalesced for a single moment.53

If oral histories are a record of the past, the coproduction of this assemblage of information reveals that such testimony not only records the past but shifts the present, altering how and what we chose to study. The converging and diverging paths of this interview reveal oral history as a live performance of knowledge production, rather than a record of a history fully past. Thus, this interview is neither biography nor history, at least neither purely. Rather, it is an attempt at permitting and valuing the intersecting, “indeterminate encounter” of historical research, revealing the productive tension between the autonomy of memory and the coauthorship of recollection, a reminder that through our collective memory, the past is always present.

Acknowledgments

I’m ever grateful to the Center for African Studies at Stanford University, in particularly the leadership of Laura Hubbard and the expertise of Richard Roberts, for support of this project.

Notes

- Playing upon the expanded field of assemblage, identified by Bill Brown as the expansive set of encounters which develop from “catalyzing an oscillation between material specificity and conceptual abstraction,” this interview plays with memory as an encyclopedia of references to reveal its multiplicity, even if from a singular individual. Bill Brown, “Re-Assemblage (Theory, Practice, Mode),” Critical Inquiry 2 (2020): 262. See also Luisa Passerini, Memory and Utopia: The Primacy of Intersubjectivity (London: Equinox, 2007). ↩

- Alessandro Portelli, The Death of Luigi Trastulli, and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1991), vii. Ironically, Portelli cites 1969 as the pivotal year in his life—intellectually and personally. ↩

- Portelli, Death of Luigi Trastulli, iii. A robust archival project interlacing four festivals, the PANAFEST Archive also features oral histories, witnessing, and interviews, a “mindmap” of the correlated histories, including Elaine Mokhtefi’s. Yet in the sonic web of the past, her unique voice is overshadowed by a web of male actors. PANAFEST Archive, CNRS, 2020, http://webdocs-sciences-sociales.science/panafest/. ↩

- Anna Tsing reminds us that “to listen to and tell a rush of stories is a method. And why not make the strong claim and call it a science, an addition to knowledge? Its research object is contaminated diversity; its unit of analysis is the indeterminate encounter.” Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 37. ↩

- Nathan Hare, “A Report on The Pan-African Cultural Festival,” Black Scholar 1, no. 1 (1969): 3–4. ↩

- The thirty-one countries participating in the festival were Algeria, Cameroon, Congo-Brazzaville, Congo-Kinshasa, Côte-d’Ivoire, Dahomey, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinee, Guinee-Bissao, Iles du Cap Vert, Ile-Maurice, Kenya, Liberia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, République Centrafricaine, Senegal, Somalia, Soudan, South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, Zambia, Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), and Zimbabwe. ↩

- Hare, “A Report,” 10. ↩

- Bentley Le Baron, “Négritude: A Pan-African Ideal?” Ethics 76, no. 4 (1966): 269. ↩

- See David Boucher’s critique as well as the novels of V. S. Naipaul for examples of decolonial failures. Boucher, D. (2019), “Reclaiming history: dehumanization and the failure of decolonization”, International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 46 No. 11, pp. 1250–1263. ↩

- On aesthetic terms, see Bennetta Jules-Rosette, Black Paris: the African Writers’ Landscape (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998); P. Tolan Szkilnik, “Flickering Fault Lines: The 1969 Pan-African Festival of Algiers and the Struggle for a Unified Africa,” Monde(s) 1, no. 1 (2016): 167–184. On the chronology of festivals, see Samuel D. Anderson, “‘Negritude Is Dead’: Performing the African Revolution at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival (Algiers, 1969),” in The First World Festival of Negro Arts, Dakar 1966: Contexts and Legacies, ed. David Murphy (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016); Dakar 66: Chronicles of a Pan-African Festival, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, February 16–May 15, 2016. On solidarities, see Meghelli, Samir, “From Harlem to Algiers: Transnational Solidarities Between the African American Freedom Movement and Algeria, 1962–1978,” in Black Routes to Islam, ed. Manning Marable and Hishaam Aidi (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009). ↩

- Hare, “A Report”; William Klein and Antoine Bonfanti, Festival Panafricain D’alger: Film Culte Et Méconnu!; Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther, France: Arte Editions, 2010; Portelli, Death of Luigi Trastulli. ↩

- Organization of African Unity (OAU), Charter of the Organization of African Unity, May 25, 1963, accessed https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/7759-file-oau_charter_1963.pdf. ↩

- Organization of African Unity, “News bulletin”, All-African Cultural Festival (1969), 8. ↩

- “Panafrican Cultural Manifesto”, All-African Cultural Festival (Addis Ababa: Press & Information Division, OAU General Secretariat, 1969), 9. ↩

- Mériem Khellas, Le Premier Festival Culturel Panafricain: Alger, 1969: Une Grande Messe Populaire (Paris: Harmattan, 2014), 40–41. ↩

- Algerian Nationality Code, Law No. 63-69, section 34 (1963). ↩

- Bronwen Manby, “4:3: French Territoires,” in Citizenship in Africa: The Law of Belonging (Oxford: Hart, 2018), 65. ↩

- Nationality Law, Law No. 1970-86, (1970), www.refworld.org/cgibin/texis/vtx/rwmain/opendocpdf.pdf?reldoc=y&docid=5b8fa1ba4. ↩

- Kathleen Cleaver, “Back to Africa: The Evolution of the International Section of the Black Panther Party,” in The Black Panther Party (reconsidered), ed. Charles E. Jones (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1998), 218. ↩

- El Moudjahid. Algiers, Algeria: Entreprise national de presse, May 13, 1969. ↩

- El Moudjahid. ↩

- Dominique Malaquais and Cédric Vincent, “Entangled Panafrica: Four Festivals and an Archive,” mezosfera.org, May 2018, http://mezosfera.org/entangled-panafrica/#fn-8114002. ↩

- Hare, “A Report,” 3. ↩

- El Moudjahid. Algiers, Algeria: Entreprise national de presse, July 13–14, 1969. ↩

- Le Baron, “Négritude,” 273. ↩

- Hare, “A Report,” 5. ↩

- “Panafrican Cultural Manifesto.” ↩

- Hare, “A Report,” 5. ↩

- Hare, “A Report,” 6. ↩

- For more on this cross-connection, see Marie-Pierre Ulloa, Le nouveau rêve américain: du Maghreb à la Californie (Paris: CNRS éditions, 2019). ↩

- “Archie Shepp, We Have Come Back Festival Panafricain d’Alger en juillet 1969,” www.youtube.com/watch?v=5GQKwcKSLOU. ↩

- Hare, “A Report,” 4. ↩

- Ian Birchall, “France 1968,” in Revolutionary Rehearsals, ed. Colin Barker (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2002), 23. ↩

- Kathleen Cleaver, “Art and Revolution: Black Power at the 1969 Pan-African Cultural Festival,” Truthout, September 29, 2016, https://truthout.org/articles/art-and-revolution/. ↩

- Cleaver, “Art and Revolution.” ↩

- Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (New York: New Press, 2007), xi. ↩

- Michael Adas, “Contested Hegemonies,” Making a World After Empire: The Bandung Moment and Its Political Afterlives, ed. Christopher Lee (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010), 96. ↩

- See A. I. Dawisha, Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century: From Triumph to Despair (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003). ↩

- There are two notable unifications which persist in the twenty-first century: the unification of seven emirates as the United Arab Emirates, and the unification of North and South Yemen to form Yemen. The Ba’ath party also continues today in the Syrian region, promoting Pan-Arabism. ↩

- Hare, “A Report,” 3. ↩

- Olivier Hadouchi, “‘African Culture Will Be Revolutionary or Will Not Be’: William Klein’s Film of the First Pan-African Festival of Algiers (1969),” THIRD TEXT-LONDON- 1 (2011): 117. ↩

- Cleaver, “Art and Revolution.” ↩

- Khellas, Le Premier Festival Culturel Panafricain, 30. ↩

- Nelson Mandela, The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (London: Abacus, 1995), 355. ↩

- Jeffrey James Byrn, Mecca of Revolution: Algeria, Decolonization, and the Third World Order (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016). ↩

- Many of these articles, originally published anonymously in El Moudjahid, would be collected in the posthumously printed book, Toward the African Revolution: Political Essays by Frantz Fanon (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1967). ↩

- “Histoire Terminale Série S,” ÉduSCOL, Ministère Éducation Nationale, 2014. https://cache.media.eduscol.education.fr/file/lycee/12/3/01_RESS_LYC_HIST_TermS_th1_309123.pdf. ↩

- Hadouchi, “African Culture,” 117. ↩

- Other footage, if less frequently cited, certainly exists, such as Théo Robichet, Alger ’69 (1971, Paul Thiltges Distributions, Luxembourg, and La Bascule, France, 2008), 16 minutes. ↩

- “Algeria Presidential Election: Five Candidates Announced,” Algeria News | Al Jazeera, November 2019, www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/11/algeria-presidential-election-candidates-announced-191103064535822.html. ↩

- “Algeria Presidential Election.” ↩

- Assia Djebar and Walid Garn, Rouge l’Aube—pièce en 4 actes et 10 tableaux (Alger: SNED, 1969), 102. ↩

- Passerini, Memory and Utopia, 8. ↩