This article tracks my intellectual journey in trying to understand the role played by craft specializations before the colonial era in KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa), which is the area where I come from. I do this by a comparative look at how craft specializations happened in other parts of the African continent, an approach prompted by the absence of older written or documentary sources on KwaZulu-Natal, prior to the advent of European colonialism. A key finding of the research is that the cultural and ritual repertoires of craft specialists reveal conceptual domains of expertise that are derived from intra-African regional dynamics. This contrasts with the colonial belief that implied that notions of expertise were as a result of European or Asian human contacts. In looking at craft guilds, I am interested in how ritual, technological skill and the mastery of certain musical/creative acts played a part in the formation of regional blocs in ancient Africa. Such a historical understanding may be crucial to our present-day understanding of emergent processes of regionalization and identity formation.

Keyword: Africa

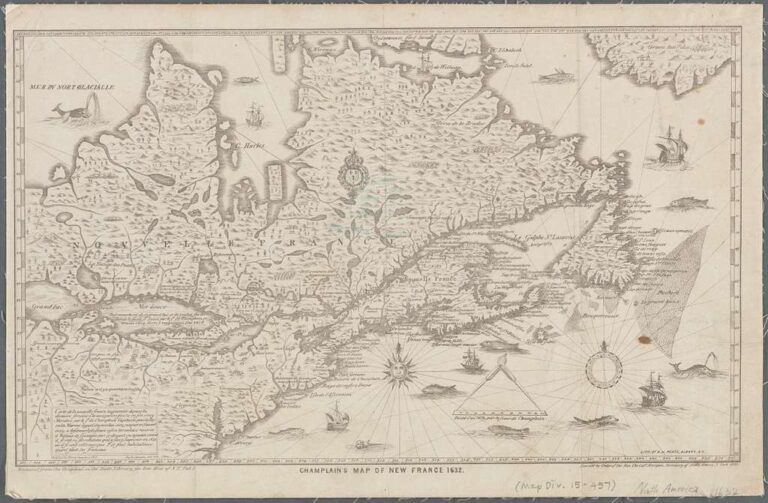

Canada’s Colonial Project Begins in Africa: Undoing and Reworking the Inaugural Scenes of Colonial-Racial Violence

Black captivity and colonial violence in New France are distinct but interlinked social formations. This article develops an analysis of captive-colonial violence in Canada by tracing how these two formations are interlinked in practice and in discourse. It examines two “inaugural” scenes: the capture of a “Black Mooress” on the coast of present-day Mauritania in 1441 and the 1603 meeting between a French expedition and the people they called “Savages” on the shores of the St-Lawrence River in Canada. The first pertains to anti-Black violence and captivity. The second pertains to colonial violence and genocide. While the two scenes are usually treated as analytically distinct, as well as temporally and geographically distant, this article brings them together. Doing so is important as it shows how the practical and discursive conditions leading to the two scenes overlapped and how each scene depends on the other. This reading of captive-colonial violence disrupts linear conceptions of time and discrete conceptions of geography to pull “distant” scenes into proximity. Through this approach, the article shows how the two scenes are interlinked in the formation of a new lingua franca of anti-Black violence and genocidal colonial violence in Canada, however different and/or incommensurable they may be