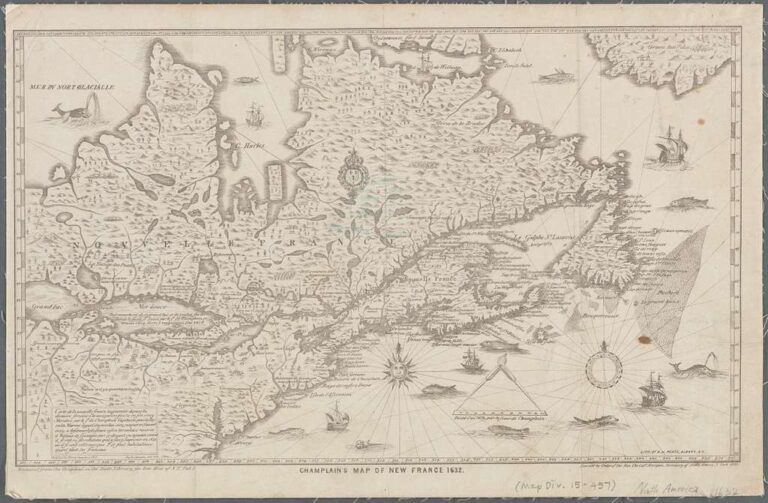

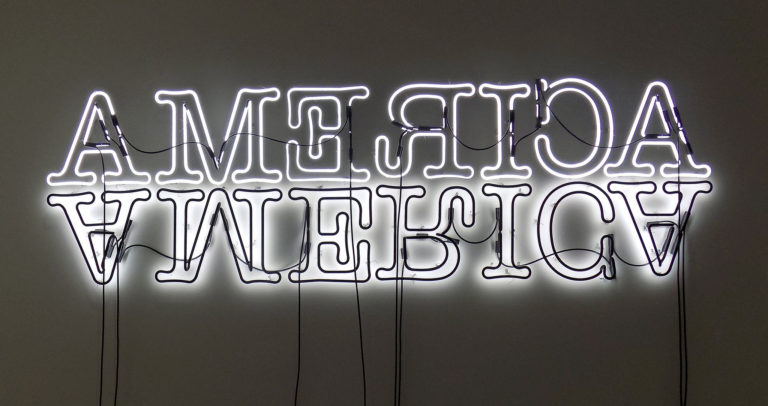

Black captivity and colonial violence in New France are distinct but interlinked social formations. This article develops an analysis of captive-colonial violence in Canada by tracing how these two formations are interlinked in practice and in discourse. It examines two “inaugural” scenes: the capture of a “Black Mooress” on the coast of present-day Mauritania in 1441 and the 1603 meeting between a French expedition and the people they called “Savages” on the shores of the St-Lawrence River in Canada. The first pertains to anti-Black violence and captivity. The second pertains to colonial violence and genocide. While the two scenes are usually treated as analytically distinct, as well as temporally and geographically distant, this article brings them together. Doing so is important as it shows how the practical and discursive conditions leading to the two scenes overlapped and how each scene depends on the other. This reading of captive-colonial violence disrupts linear conceptions of time and discrete conceptions of geography to pull “distant” scenes into proximity. Through this approach, the article shows how the two scenes are interlinked in the formation of a new lingua franca of anti-Black violence and genocidal colonial violence in Canada, however different and/or incommensurable they may be

Keyword: Canada

Webs of Relationships: Pedagogies of Citizenship and Modalities of Settlement for “Muslims” in Canada

Immigrants to Canada must pass a set of pedagogical gate-keeping exercises that compel settler socio-spatial relations to allow them to come into the fort of the nation-state as neoliberal multicultural subjects. Bringing together Sunera Thobani’s concept of exalting the white subject and Sherene Razack’s theorizations on Muslim eviction from Western politics, I argue that those racialized as Muslim are positioned as perpetual immigrants, compelled to exalt whiteness or be evicted. Caught between an unresolved tension of settler spatial relations to nation and Indigenous spatial relations to Land, I examine what decolonial subject positions are available for “Muslims” using the Canadian citizenship study guide and oath as focal points. I foreground an Indigenous analytic and my Arab lived experience to do a contrapuntal reading of the social construction of Canada in the study guide and trace how the relationships to nation espoused in the manual are incommensurable with the relationships to Land fundamental to Indigenous worldviews. Throughout the paper, I draw on the experience of Masuma Khan, who was censured by her university and the public when she advocated that Canada 150 be remembered as Indigenous genocide rather than a celebration of nationhood, to unpack how racialization colonizes and colonization racializes.

Review of Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism by Iyko Day (Duke University Press)

Iyko Day makes a compelling intervention in discussions of race, capital, and settler colonialism. Her book presents a theorization of the abstract economism of Asian racialization by examining how social differentiation functions as a destructive form of abstraction anchored by settler colonial ideologies of romantic anticapitalism. By engaging with capitalism’s abstraction of differentiated gendered and racialized labor in order to create value, Day’s project diverges from scholarship arguing that capitalism profits from labor via the production, rather than the abstraction, of racialized difference (Lowe 1996; Roediger 2008). Her book engages a rich multimedia archive and uses principal historical instances of Asian North American cultural production as theoretical texts to examine key racial policies since the 19th century: Chinese railroad labor in the 1880s, anti-Asian immigration restrictions; internment of Japanese civilians during World War II, and the neoliberalization of immigration policy in the late 1960s.