In a well-known formulation, Vijay Prashad wrote that, “The Third World was not a place. It was a project.” This forum feels out ways to understand and remember the Third World project as a collective horizon of freedom enacted by ordinary people in their daily lives. Beyond the political leadership of the iconic leadership of Third World state leaders and the foundational conferences they convened, we seek to explore how the Third World was lived and imagined. We do so as an invitation to fellow teachers and students to deepen collective imagining through a twin process of learning and unlearning. Formulated as a practice of Third Worlding, this invitation is a proposal to make historical precedents familiar and make progressive visions of intersectional, anti-racist, decolonial struggle strange. It seeks out other ways of calling comrades into political practices by exploring the ways in which Third World subjects imagined and related to each other. In this introduction, we lay out what Third Worlding might offer as a tool for reorientation in the political present.

Towards Third Worlding

Edited by Rayya El Zein & Malav Kanuga

This forum feels out ways to understand and remember the Third World project as a collective horizon of freedom enacted by ordinary people in their daily lives. Formulated as a practice of Third Worlding, this forum seeks out other ways of calling comrades into political practices by exploring the ways in which Third World subjects imagined and related to each other.

Decolonization and the Third World

This essay asks why the Third World has become a symbol of poverty and failed infrastructure while the political imperative towards decolonization has gained popularity. By examining histories of decolonization in mid-twentieth century and the subsequent establishment of postcolonial nation-states that often ignored, suppressed, or actively participated in settler colonial occupations both globally and internally, I argue that there needs to be a widespread reckoning with what constitutes anti-colonial liberation.

The Captive New Afrikan Nation, the Politics of Solidarity, and the Ongoing Struggle for Liberation

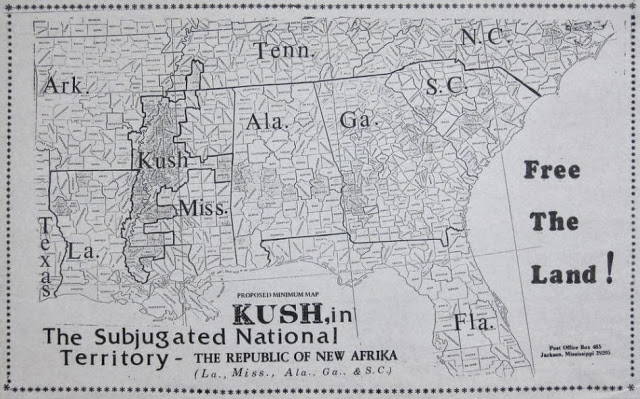

In 1968, the world was changing. New nation-states were forming as former colonies revised relationships between Africa, Asia, and the “West.” Some fought hard for their liberation, and some were still fighting. From Vietnam to Zimbabwe, bloody struggles against racist settlers and western capital clarified the tenacity of white supremacy and imperialism. Other nations were “peacefully” exchanging white political leadership for parties and personalities rooted in local soil. All excited the US Black left who welcomed the changes as the ideal condition for Black liberation. Among them were activists who, beginning in March 1968, decided to pursue the creation of an independent Black nation-state that would occupy land in the Deep South. Considering Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, and Georgia as the rightful territory of their Republic of New Afrika, those who championed independence sought to replicate the apparent successes of Tanzania and other newly formed states, while contributing to the complete overthrow of western hegemony. This contribution explores the theory of the New Afrikan struggle for land and independence. It considers how New Afrikans negotiated their African ancestry and colonized status with their distinctly North American position within geopolitics. In asserting their right to self-determination, New Afrikans complicated the meanings of captivity and Third World solidarity in ways unique to the Black Power era. Even as they built on their predecessors from the African Blood Brotherhood, UNIA, and even the CPUSA, New Afrikans helped to frame their era’s political ideas in a manner that continues to guide projects of international liberation and solidarity.

Reawakening Ali Sardar Jafri’s Asia Jaag Utha

The epic poem Asia Jaag Utha, written in 1950 by Ali Sardar Jafri of the Indian Progressive Writers Association, was a battle hymn of its time, a celebration of Asia’s history and geography, with a vision for Asian liberation and communist revolution at the dawn of the Cold War in the aspirational Third World. Are its messages still applicable today, or is it strictly a period piece? This essay analyzes what Jafri was trying to do in his own context and explores whether it has anything to say to ours. In order to do this, the author enters into dialogue with Jafri’s poetry, and proposes some updates to its political agenda that might be needed to carry its energy into the present. While the mid-twentieth century vehicles of progress and liberation (such as industrial development and the postcolonial nation-state) require critique, Jafri’s emancipatory impulses and ideals of solidarity ring true.

Anti-Colonial Defeat: The 1967 Naksa and Its Consequences

This entry asks what it means to mourn the loss of the state as a vehicle for revolutionary liberation. State power was indeed authoritarian, and global solidarity in the era of the Third World Movement of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s was superfluous, but it still meant something to people then and now. Losing it was felt. In this piece, I revisit the 1967 Arab defeat against Israel known as al-Naksa (the resounding setback) within the context of the Third World movement and its influence on global solidarity in the ensuing decades following 1967. I focus on the loss of Egypt’s position as an anti-colonial leader after the 1967 war and subsequent death of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1970. Egypt, once a bastion of revolutionary anti-colonial fervor at the nexus of Pan-Arab and Pan-African imaginaries, and a hub of the historic Third World, became radically realigned with the Global North under Anwar Sadat. I argue that the fate of the Egyptians, Palestinians, Arabs, and of anti-colonial global struggle each became unlinked and siloed as individual struggles. It is not just Arabs or Egyptians or Palestinians who were defeated, it was a whole anti-colonial ethos. How do we mourn the loss of the state as a vehicle for liberation, for Palestinians, for Arabs, for Africans, and for the post-colony?