Aya of Yopougon is a bande dessinée (BD, or graphic novel in North American parlance) in six volumes. Originally published in French in 2005, it is the story of a young woman and her peers coming of age in the West African nation of Côte d’Ivoire at the end of the 1970s, during a period referred to as the “Ivorian Miracle.” Originally published in France by Ivorian-born author Marguerite Abouet, with artwork by her husband, illustrator Clément Oubrerie, Aya has since been translated into over a dozen languages. It was the first work by an African author to win the Best First Album Award at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in France, and it has also been adapted into an animated film1

This article aims to contribute to a relatively recent move in feminist and queer approaches to literature and popular culture that value “weak” rather than “strong” theoretical priorities. Amid strong theories of postcolonial and queer diasporic cultural production that identify newly ascendant historical forces as the causes for emergent patterns in narrative, I appraise Aya as a popular text of a different color—its representation of postcolonial Africa and Africans in diaspora portrays “novelty” rather than determination. I coin the term novelty here to describe how Abouet and Oubrerie’s work contrives impressions of everyday life whose aggregate effect is comparatively humble: its imaginative vision works toward the potential to surprise observers and interpretants. This orientation toward potentiality is an alternative to a more systematic, knowing agenda invested in determinacy; whereas the former lends itself to theories concerned with poesis, the quotidian, and concrete description, the latter tends toward global and prescriptive theories that correlate cultural forms with historical developments in more decisive terms.

While “correlationism” has come under scrutiny in contemporary philosophy, my interpretation of Aya as a text amenable to weak theory is agnostic toward these debates. The contrast between a weak theory of novelty and a strong theory of political efficacy echoes Isaiah Berlin’s classic treatment of the parable of the fox and the hedgehog: the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Novelty appeals to the multifarious, cosmopolitan aptitudes of contemporary African diasporic authorship as a discursive formation that eludes the power of nation and capital in subtle ways but does not altogether escape them. Rather than realizing the impact of decolonization or neoliberalism on the medium of the graphic novel, Aya synthesizes conventions from a variety of visual and narrative traditions to address a heterogeneous readership. In keeping with the tendency of market-watchers and cultural critics who cite the fox/hedgehog distinction, my interpretation of Aya “does so in order to celebrate the virtues of being a fox.”2 The analogy operates here to distinguish my weak theorization of novelty in Aya from the systematic approaches to postcolonial African and diasporic literature that apply to various moments in the graphic novel. Aya facilitates the elaboration of an eclectic repertoire for contemporary African diasporic authors and artists who are learned in many traditions rather than inaugurating a new school.

This article discusses how Aya of Yopougon eludes the “symptomatic” reading strategies characteristic of strong theories. A deterministic model of the relationship between textual forms and their conditions of possibility would trace features of the African diasporic graphic novel to the post-Cold War realignment of African governance characterized by the rise of multi-party states and multilateral agreements, the decentering of colonial legacies and neocolonial discourses by new media practices and postcolonial critique, and the proliferation of new relations to national identity. Although these hypotheses pertain to some qualities of Aya that it shares with other texts, they are founded on a certainty about the present that Aya disavows by turning to the past. Strong theories and the reading practices to which they give rise “confer epistemological authority on the analytic work of exposure . . . which gives the critic sovereignty in knowing, when others do not, the hidden contingencies of what things really mean.”3 Reading Aya according to the hypothesis that no single epistemology of language, mediation, or subjectivity subsumes its significance is this article’s means of ceding authority back to the intellectual milieu out of which it emerges.

As an object lesson in the value of a weak theory of cultural production, Abouet and Oubrerie’s rendition of the past outlines an alternative to the challenges of the present that it cannot currently enunciate in the form of a political objective. Instead, it recalls a specific, “no longer conscious” moment at which a way of life beyond the contingencies of the present seemed possible.4 I argue that the narrative does not lend itself to a program of interpretation or action that can bring about that way of life. It does not indict the forces that have made desirable realities from the past unattainable in the present, but it stages an intervention into the historiography of postcolonial Africa, nonetheless. Emphasizing its diversionary and ludic aims, my reading of Aya questions how the text redeploys facets of its setting to inspire plural ways of knowing the past rather than recommending particular directions for future action. Like vernacular speech, performance, self-fashioning, and other weakly articulated but familiar everyday knowledge practices, African comics “literally can’t be seen as a simple repository of systemic effects imposed on an innocent world.”5

I describe the text’s production of novelty as an elusive rather than resistant strategy in order to specify its mode of addressing the political. I argue that Aya’s diversionary agenda rehearses a utopian tendency in culture akin to what José Esteban Muñoz terms “queer futurity.”6 Aya foregrounds the time and place called the “Ivorian Miracle” to divert the reader’s attention away from the urgency of the here and now. It focuses instead on a “then and there” at which the most salient questions of the moment in which we live are markedly absent. This small-scale utopianism staves off the “ossifying effects of neoliberal ideology and the degradation of politics brought about by representations of queerness in contemporary popular culture.”7 Unlike what Muñoz terms abstract utopia—in which an ideal way of life emerges out of changes in social structures that can be understood at a high degree of abstraction—concrete utopia, a genus in which I argue queer futurity and novelty are species, marks out the residual and ephemeral spaces where desirable possibilities become legible in everyday terms.

Although the narrative does not address them head-on, Abouet identifies negative portrayals of postcolonial Africa that prevail in Europe and North America as one of her motivations for writing Aya.8 Alisia Grace Chase echoes this aim in her preface to the first volume of the text: “the western world is becoming increasingly aware of the myriad cultures on this massively diverse continent, but swollen bellied children, machete wielding janjaweeds, and too many men and women dying of AIDS continue to comprise the majority of visual images that dominate the Western media.”9 Acknowledging that contravening the dispiriting effects of dominant media imagery was one of Aya’s premises, I argue that its approach to addressing the ills of contemporary discourse on Africa and Africans in diaspora is “reparative,” that is ameliorative, rather than corrective; it does not reveal and explain the unexplained but seeks to improve on conditions that are known to be unsatisfactory.

As Eve Sedgwick posited in coining the term reparative reading, the “hermeneutics of suspicion” that came to dominate critical theory in the twentieth century was only one of a number of possible interpretive orientations. Sedgwick derives the language of paranoid and reparative modes of interpretation, the methodological analogues to strong and weak theory, from the work of psychologist Silvan Tomkins. In the now-classic essay “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading,” she writes that the program of knowing prescribed by strong theories is “monopolistic,” placing all its faith in

demystifying exposure: only its cruel and contemptuous assumption that the one thing lacking for global revolution . . . is people’s (that is, other people’s) having the painful effects of their oppression, poverty, or deludedness sufficiently exacerbated to make the pain conscious.10

Because the text seems to disavow any role in bringing about global revolution through the exposure of hidden sources of pain, my search for novelty in Aya of Yopougon admits into the sphere of valuable lessons the possibility that the text aims to mitigate the deleterious effects of dominant imagery on the cultural landscape by offering diversions from the harsh realities portrayed elsewhere. These diversions are grounded in everyday life and largely specific to the author’s vantage point on recent history.

My reading of Aya concurs in the hypothesis of the “Ivorian Miracle” that Abouet advances rather than calling it into question. This setting asks readers to be credulous about the past by foregoing speculation about its relationship to the present. Whereas symptomatic reading is concerned, even obsessed, with successfully arriving at irrefutable explanations for far-ranging phenomena, weak theories take an interest in appreciating what cultural endeavors intend to achieve locally and learning from what happens when they seem to fail.11 My reading of Aya therefore resists scrutinizing Abouet and Oubrerie’s rendition of the Ivorian Miracle along the lines of success or failure, downplaying the issue of whether their reconstruction of the epoch corresponds to evidentiary accounts. Instead, I explore how the text seeks to confer a wider array of images of postcolonial Africa and Africans in diaspora to the political imaginary of readers and critics.

My interpretation of Aya takes a reparative approach by framing Abouet and Oubrerie’s rendition of the Ivorian Miracle as a reparative reading of the historical record. Like many French colonies, Côte d’Ivoire attained independence in 1960. But unlike its neighbors, the country levied high taxes on the small farms that produced cocoa and coffee for export, encouraged immigration, and saw remarkable economic growth as the cash crops became more lucrative.12 The economic miracle fueled capital accumulation within the country (and among foreign investors) without distributing the benefits of growth to all stakeholders equally. Cities like Yamoussoukro and Abidjan reaped the benefits, along with their prosperous suburbs like Abouet’s childhood home, Yopougon.13 Aya makes use of this uneven development not to draw contrasts or expose contradictions but to affirmatively identify a local context where signs of relative prosperity preponderate. The characteristics of that time and place, a vibrant Yop City, rationalize shared stability and low-stakes dynamism as contours within which the narrative can eschew considerations of deep poverty and structural conflict.

Insofar as life in upwardly-mobile Yop City is the point of departure for the characters’ shared experiences, they share a common relation to their community. Within the constraints imposed by the circumscribed outlook on just what there is to represent, above, I examine how Abouet and Oubrerie “build small worlds of sustenance that cultivate a different present and future” for the ways of life they place on display.14 The following discussion of Aya of Yopougon outlines its construction of novelty in the context of other African and diasporic texts, as well as comics produced elsewhere and relevant criticism, in order to elucidate the possibilities imagined in its pages.

There are three dimensions in which the text eludes symptomatic interpretations that would construct its features as effects of a singularly discernible structural phenomenon: language, form, and mobility. Aya corroborates several theories regarding “minor” literatures, including postcolonial African literature, but only in part, in its representations of speech. I discuss how aspects of the text that draw attention to its cultural specificity persist into its English translation and how it deploys rhetorical devices without conforming to any particular doctrine regarding the role of language in postcolonial cultural politics. Subsequently, I analyze Aya’s visual style in relation to globally influential comics traditions, addressing recent scholarly efforts to develop a more systematic perspective on African interventions in the medium.15 Finally, my analysis concludes by reflecting on diasporic movements in the text, including Abouet’s emigration from Côte d’Ivoire to France, with attention to the way these itineraries “underperform” emergent critiques of queer diaspora that encompass questions of economics, nationalism, and gendered and sexual identity.

Speaking of Modernity

Although it does not diagnose the legacy of the recent past through a symptomatic treatment, Aya’s Ivorian Miracle is not a distortion but a “double,” a new quantity that is distinct from but similar to its antecedent. As Achille Mbembe has noted, discursive apparatus such as comics and speech create “doubles” with the capacity to participate in their respective discursive conventions.16 Aya is not a proxy for Abouet within the text, but she is a double for the author function. Like the protagonists of other BD, she confers her name to the text’s constituent parts and holds the narrative together on a formal level.17

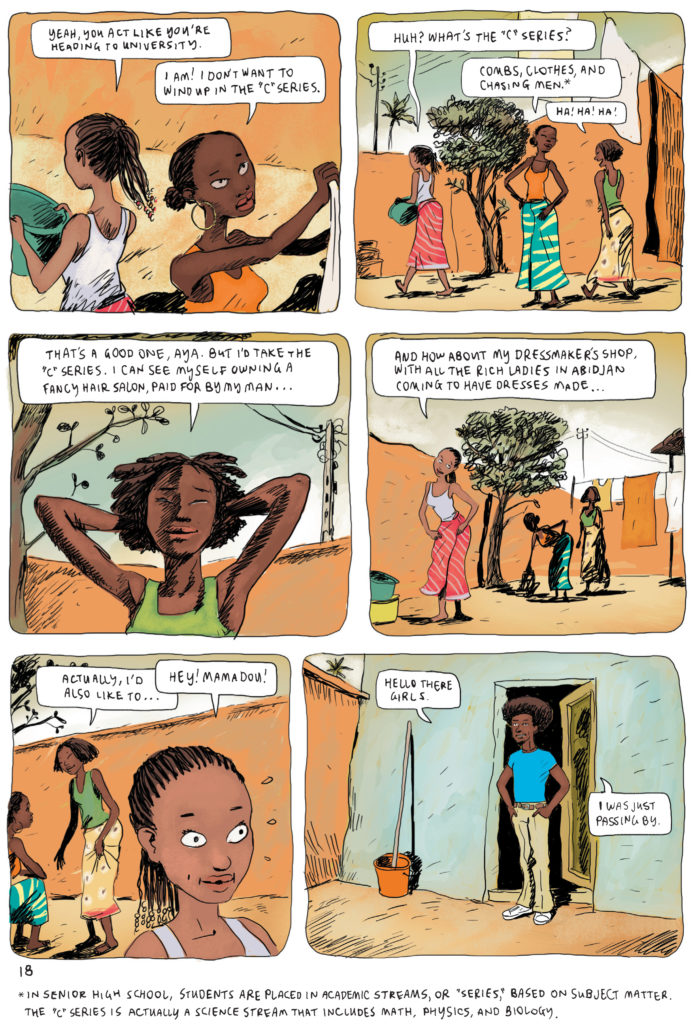

An important doubling within Aya’s rendition of the Ivorian Miracle is its representation of the educational system Ivorians have inherited from France. The studious Aya aspires to become a doctor, and she plans to attend university. She jokes that she does not want to “wind up in the C-series.”18 This reference is a double entendre, invoking both the name of an actual course of study in French institutions that includes certain academic subjects (math and science) and another set of terms with trivial connotations: “combs, clothes, and chasing men.”19 The joke illustrates how young women coming of age view their options in the country’s changing economy. Aya and her best friends Adjoua and Bintou, as thoroughly modern women, gently mock the idea that their future will be limited by gender, but they know that education could make the difference between full citizenship and economic equality with men, on the one hand, and disenfranchisement, on the other.

The individual terms in the phrase C-series translate efficiently from Francophone to Anglophone editions of the text—the original text is “coiffure, couture, et chasse au mari”—but the use of the term C-series does not. The partial translatability of the joke across cultural frames of reference marks this text with the specificity of its Francophone origins as well as the global reach of liberal feminism. Unlike certain modes of postcolonial discourse, the way Aya plays up the contradictions of official language, in this instance, provides the characters with a sense of continuity in their experience of the transition to a new phase of modernity. Here, Abouet makes use of what Mikhail Bakthin defines as “ritual laughter,” which critic Marc Caplan describes as “a means by which a traditional culture makes productive use of its internal contradictions . . . a crucial defense mechanism in the reconfiguration of the tradition as a counterbalance to modernity.”20 In this instance, the “tradition” interrogated by the characters’ discussion of career paths is a set of gender roles confronted by modern women in the course of achieving individual success independent from marriage. The transposability of the terms comprising the C-series results from the “carnivalesque” capacity of language to invoke contradictory concepts to the same signifiers: C-series might describe women who transgress gender norms to enter a learned profession, or it might belittle women who devote their formative years to superficial beauty pursuits. The same conversation could take place simultaneously among white teenagers in France; African, European, and North American women alike confront modernity by moving away from the same gendered traditional division of labor.

In an interview with Angela Ajayi, Abouet describes newfound autonomy among women as a consequence of the Ivorian Miracle; notably, she cites “access to the pill,” a historically specific development typically associated with European and North American women’s movements rather than those of the Global South.21 Abouet’s deployment of ritual laughter in reference to changing traditions associates Côte d’Ivoire with the rest of the Francophone world, but it echoes a strategy that some other African writers pursue by employing proverbs to represent culturally specific oral traditions persisting in the face of colonial and neocolonial influences. The appearance of proverbs in literary texts can elicit ritual laughter by situating local knowledge practices structured by oral traditions on the written page, representing the adaptability of tradition and its value as a resource in the process of modernization.22

Abouet occasionally makes use of proverbs in a fashion that serves this purpose, but she demonstrates the exception to this tendency through a character in a diasporic location. Because proverbs rely on the sharing of knowledge via oral communication, when an Ivorian character tries to use one in order to stop members of a French family from having an argument at the dinner table, his effort falls flat. The proverb, “Remember: an angry bull can’t mount a cow in heat!” inspires quizzical expressions.23 Without a shared episteme among the communicants and the reader that makes this proverb familiar, the encounter between Africans and Europeans becomes an unsettling moment in modernity rather than an occasion to affirm the value of tradition.

Authors including Côte d’Ivoire’s Ahmadou Kourouma and Nigeria’s Wole Soyinka, on the other hand, employ what Caplan calls “deformative laughter,” a frequently satirical comic repertoire that plays up the absurdities of colonial life and death in order to “undermine the modern order that has displaced tradition.”24 This strategy often involves transliterating words between African and European languages or exploiting homophony to expose the incoherence, from an indigenous frame of reference, of colonial discourse.25 Caplan’s account of deformative laughter is an artifact of a strong theory: it focuses on “subversive and demystifying parody, the detection of hidden patterns of violence and exposure.”26

Once we identify deformative laughter as a symptom of hidden patterns of violence, the latter is likely to proliferate everywhere we look. Sedgwick associates the suspicions of critics invested in such a strong theory with the disposition she describes as paranoid reading. Rather than the subversive parody that arises out of the aforementioned writers’ deformative uses of language, Abouet’s manner of including culturally specific material in the text is better described in the straightforward terms of juxtaposition rather than more volatile terms like deformation. Juxtaposition, the placement of pictorial and other images, including words, in proximity to one another within a text is the definitive quality of comics across traditions, according to critic Scott McCloud. Regardless of the verbal language in use, juxtaposition provides the “grammar” of comics. It enables the reader to use protocols such as reading order (left to right in BD, right to left in manga) to apprehend the relationship of one part of the page to another.27 Just as discrete elements on a page become meaningful through relations such as sequence and difference (e.g. the difference between verbal and pictorial images), the scenes, chapters, and narratives consist of cohesive sets of juxtaposed elements that readers learn to recognize through repetition and contextualization.28

Aya plays up internal contradictions within the verbal language in which it was composed, French, to achieve ritual laughter, suturing the meaning of tradition within a Francophone context. It carries this investment in a metropolitan sensibility across translations into other languages. But it translates aspects of the text that were not initially inscribed in the text in French in a much more discrete fashion. Across its many translations, Aya maintains a clear hierarchy between the elements conveyed through verbal language and amenable to translation, on the one hand, and the discursive objects identified with African sources, on the other. Using juxtaposition to suggest transparency, Aya reproduces and rationalizes order rather than pointing to instability or epistemic violence through its configuration of objects and their meanings. The somewhat idiomatic quality of the phrase “C-series,” for instance, requires explanation within the flow of the narrative. The dialogue incorporating this term in the English edition of the book contains an asterisk referring to some English text at the bottom of the same page where characters speak the phrase. On the scale of the book-length object as a whole, however, Abouet and Oubrerie relegate translations of Ivorian colloquialisms that occur on many pages to an extradiegetic site within each volume of the text.

There is a section at the end of each volume of Aya titled “Ivorian Bonus.” The material in this section includes a glossary for words like koutoukou (a palm wine-based beverage) and dêh (an interjection), reinforcing their novelty for the presumptively non-African reader. Across the six volumes of Aya, the “Ivorian Bonus” delivers educational, cultural, and biographical background information. Highlights include a recipe for peanut sauce and a discussion of the care of newborns in Ivorian households. Separated from the narrative by a page that features a silhouette of the African continent on which the only detail is an outline of the borders of Côte d’Ivoire, the Ivorian Bonus is a reminder that the translation and circulation of texts as commodities for a differentiated reading public accrues ideological implications that might countermand either strong or weak theoretical accounts of their contents. Book covers, prefaces and epilogues, and consumer-oriented packaging can flatten out the nuances of African and Asian writers’ works published in European and North American languages.29 Perhaps out of its authors’ sense that centers and peripheries take shape despite readers’ best efforts to resist them, the physical structure of each volume of Aya inscribes central and peripheral reading protocols in which whatever is universally legible, generically African, characteristically Francophone, or specifically Ivorian about the text can be apprehended through a simplifying, didactic mode that addresses the reader directly. Knowledge flows through the text in ways that are inflected by market imperatives and also contrived by the author and her collaborators, making it as plausible to describe Aya’s uses of verbal language in the weak theoretical terms of novelty, ritual laughter, and the “bonus” or supplement, rather than conscripting it into a stronger theorization of the conditions of its legibility that would implicate a wide array of other texts. The question of how to associate Aya with other comics is my concern below.

Reliable Narrators and Formal Novelty

The creation of Aya as a synergistic collaboration between Abouet and Oubrerie, neither of whom had ever previously worked in the medium, goes a short way toward explaining Aya’s novelty among BD.30 However, the features of Aya that mark it as a unique creative synthesis are better understood as signs of its continuity with the eclecticism that has informed African comics since their inception. Recounting the developments in African print cultures that have led up to contemporary examples, Massimo Repetti notes that independence from European colonialism gave way to the global influence of American mass culture, including comics.31 While he positions the globally-ascendant form of the graphic novel at the end of this genealogy, Aya displays many qualities suggestive of autonomy or even anachronism rather than a progression of forms that culminates in the present configuration of the text.

The most ubiquitous form of comics in the first half of the twentieth century were comic strips from the “funnies” sections of U.S. newspapers, which provided the template for African artists to introduce their first “paper heroes.”32 The broad-based adoption of this mode of dissemination for African comics differentiates them from the specialist periodicals, anthologies, and book-length albums that represent the medium prominently in Europe and Japan. Newly independent Africans also produced “politico-hagiographic” comics about their national heroes. The propagandistic iconography of these comics resurfaces in diaspora in the work of Nigerian-born, US-educated British illustrator, Tayo Fatunla.33 Abouet’s nostalgia for Houphouëtism operates in the background for most of Aya, but national iconography resurfaces momentarily at the end of the narrative.34 Nonetheless, as I will discuss below, the same apparatus used to venerate national leaders and their values also lends itself to dissident caricatures and irreverence.

Another invention of African comics artists was the rendition of oral narratives in graphic form, which emerged in conjunction with orally derived literary texts by the likes of Djibril Niane. A generation of critics including Amadou Koné, Henry Louis Gates, and Achille Mbembe has problematized the Western tendency to view the influence of orality on African literatures solely in terms of traditionalism. These critics revalorize the evolving sophistication of modern African and Black diasporic speech and writing, and they draw attention to the material factors that make publishers, translators, and readers adhere to reified concepts of authenticity.35 Mbembe, using the example of BD from Cameroon, explains how African cartoonists’ most transgressive images profane the otherwise consecrated value of language in oral cultures. Conceptualizing the place of comics in societies where orality has played a paradigmatic role in shaping the public sphere allows us to comprehend what artistic license means for African artists in concrete terms. Mbembe insists that in orality-based language communities, “speech being the very foundation of experience and the primary form of knowledge,” concepts like “mere” rhetoric or “empty” words are oxymoronic.36 Pictorial signification, particularly in the iconic register of images that resemble their referents, is especially liable to “annex and mime what it represents, while, in the very act of representation, masking the power of its own arbitrariness, its own potential for opacity, simulacrum, and distortion.”37

Okwui Enwezor takes Mbembe’s argument to imply that, when pictorial signs are forms of speech, “the comic functions not as an autonomous text, but as one manifestly tethered to the political sphere. In the context of the climate of political repression . . . such a mode of expression can be taken as an excess of speech, as speech that exceeds the limits of its tolerability.”38 The limits of political speech are, by definition, hard to discern except through their exceptions. Al’Mata, an artist who fled the Democratic Republic of Congo after his caricatures of then-President Mobutu Sese Seko placed him at risk, notes that “fear of repercussions limited creativity.”39 In conversations with critics, a number of comics artists suggest that heterogeneous African print cultures first arose in societies transitioning to multiparty systems in the 1990s. The comics printed in postcolonial periodicals could venture beyond nationalist doctrines to broach important new themes as their resident states shook off Cold War polarization and the outsize influence of apartheid South Africa. In Côte d’Ivoire, publications like Ivoire Dimenche and Fraternité Matin that had introduced “paper heroes” for the previous era gave way to Gbich. The latter featured satirical figures, like “the unrelentingly lethargic” Jo Bleck and the corrupt policeman Sergent Deux Togos, who are decisively less than heroic.40

The process of repression giving way to liberalization, to which the texts above attest, offers a compelling metanarrative that makes Aya’s diminished ideological force seem right on time. But Aya is also informed by divergences from this trajectory. Comics from the 1970s and 1980s, before the rise of multiparty governments across the continent that Repetti diagnoses as the condition of possibility for new developments, show that pluralism and political commentary had already prevailed on the pages of African periodicals. Lagos Weekend depicted Wakaabout, “a combination of flanêur and urban detective, a phantom floating unseen through the murky depths of the city and the corridors of governmental power.”41 Dakar’s Le Cafard Libéré introduced the enduring underdog Goorgoorlou, “treat[ing] subjects such as inflation, politics, urban unrest and the popularity of local rap music.”42 Although there may be more texts like Aya in circulation in the present, this is not necessarily because they were impossible to produce in the past; geographic rather than temporal forces might account for the divergent attitudes toward African politics seen in comics. The Nigerian and Senegalese comic strips above made controversies visible at a time when their counterparts in other countries did not, indicating that local and national factors, rather than continental or global political shifts, dictate the circumstances for the production of print and visual culture. Aya’s diasporic point of origin may account for its neighborhood-level setting, its meek politics, and its long form.

The most influential comics emerging out of the Europe and the United States took the form of the comic strip, the English equivalent of the phrase “bande dessinée.” These comics, printed within publications featuring other kinds of texts, “rely above all on the presence of a re-occurring character who becomes a close friend of the reader.”43 According to the influential theories of French BD pioneer Rodolph Töpffer, comics create familiarity for readers by simplifying representation to its most essential graphic elements. Hence, characters can wear the same clothes and hairstyles and bear no signs of aging—even for generations at a time—because their consistency makes the changing situations in which they find themselves appear novel. The winged helmet and bulbous nose of Asterix, Little Lulu’s button-hole eyes and tiny cap, Goorgoorlou’s shaved head and his conical hat all remain intact whether the characters experience incredible drama or simple quotidian travails. For some comics that divide the labors of artist and writer, “the more distinctly and simplistically the character is drawn, the easier it is for the scriptwriter to come up with imaginative scenarios.”44 Recognizable characters can bring continuity to otherwise disparate components of a text, just as unreliable narrators can cast their coherence into doubt. Across the separate regions of the page and the many pages of a longer text, “the first thing the reader does when he or she approaches a comic strip frame is to look for the character.”45

By contrast, more individualized illustrations, like Oubrerie’s style in Aya, can imbue characters with individuality at the expense of a certain “universality” of appeal. Töpffer’s theories suggest that representing characters’ visual distinctiveness “schematically,” through caricature, corresponds to the attenuation of specificity in the visual representation of their environments. Hence, as long as the characters are present, we only need to see those elements of background detail that are essential to the narrative. In this way, caricature provides a sort of “shorthand” through which comics can emulate the narrative functions performed by sentences in “certain novel-related literature, in particular the intimate style of writing that favours intuition over analysis and fleeting impression rather than description.”46 Accordingly, “the artist need no more repeat elements of décor, such as a chair, than would a novelist need mention the chair in every sentence.”47 If all images are “effectively an extension of the character” in comics that rely on cartoon-like renditions of persons, then we might expect comics specify their characters’ features with more verisimilitude to display a concomitant tendency to flesh out the visual details of the situations they illustrate. This is precisely the case in Aya: characters’ appearances are different in more than superficial ways, and the physical environments where their actions take place are virtually always illuminated in detail.

Comics artist Jean-Claude Forest, creator of Barbarella, contends that a maximally-simplified visual style liberates the writer to create “imaginative scenarios” for the characters.48 Abouet and Oubrerie do not pursue the far-fetched range of situations that a simplified mode of visual composition would afford to the narrative; this may be a function of the text’s realism. Yet short, serial comics that are set in everyday circumstances rather than wide-ranging adventures, like Schultz’s Peanuts and the early twentieth-century BD Bécassine, rely on much simpler drawings than those of Aya, reducing the facial features and costume of characters to cartoon form and rendering their physical settings extremely sparse. To address Aya’s relatively detailed pictorial imagery, which is comparatively labor-intensive for the artist and the reader, in reparative terms, I suggest characterizing its visual style in terms of the presence of novelty rather than the lack of economy or efficiency.

Abouet describes her motivation for writing a graphic novel by inverting Forest’s account of the creative process: “my writing process rests mainly on creating character portraits . . . and my imagination is fed by their interactions. In addition, I am also very much at ease with dialogue, and this is why graphic novels came easily to me; the style is similar to theatre.”49 The analogy to theatre is telling, because unlike the “novel-related modes of writing” that Töpffer compares to comics, in which details (furniture, décor) that appear in earlier sentences need not be reproduced throughout a scene unless they are instrumental to the characters’ actions, theatrical works constantly remind the audience of the spatial environments they represent, simply because the set and props are physically present on stage alongside the actors. Abouet’s citation of theatre as a frame of reference distinguishes her approach from some recent scholarship on BD and comics in other European contexts, which derives much of its analytical language from film.50 Oubrerie’s prior experience as an animator is conspicuously absent from Abouet’s account, but his background encourages us to conceptualize Aya as a work that “casts” characters in a performance and sets them in motion according to the author’s designs.

Repetti describes Aya as part of a “trend . . . away from an age in which comics were confined to daily papers and magazines to one founded on the centrality of the book.”51 Although he credits greater professional autonomy and new relationships with European presses like Abouet’s publisher, Gallimard, with the rise of African graphic novels, these material factors do not prescribe the style of illustration seen on Oubrerie’s pages. By Repetti’s own account, many comics that emerged in strip form through periodicals like Gbich! and those that yield the first self-contained (short-form) comic books in Africa utilize a style of illustration informed by European colonial print cultures: ligne claire. Ligne claire (literally “clear line”) is a style of line drawing that “uses stark black outlines [of equal weight] both for the characters and for surrounding objects, avoiding any blurring effects.”52 It is a highly recognizable formal device that facilitates graphic simplicity, making it amenable to the aforementioned techniques for emphasizing characters over background details.

Precisely because ligne claire defines the content of the particular comics narratives that have become familiar across the globe—most notably, Hergé’s Tintin—this style has also played an integral role in defining the form by populating the pages of albums that are disseminated globally in many languages.53 Thus, while ligne claire operates efficiently in comic strips, it is also a distinguishing feature of the “centrality of the book” among comics creators in the African context and elsewhere.54 Citing the “rapid rate at which global cultural forms are indigenized by African comics authors,” Repetti notes that African artists’ use of the ligne claire “is not necessarily a sign of their desire to adapt to the European-oriented mainstream.”55 Some of the most radical experiments in the graphic arts use styles influenced by the ligne claire to ironic effect by conveying ambiguous and irreverent messages in an apparently straightforward mode of representation. Laurence Grove refers to the Pop Art of Lichtenstein and Warhol as examples of this tendency, and Conrad Botes uses the style to illustrate racial and sexual anxieties drawn from South African life.56 Contrary to a deterministic interpretation of the relationship between visual style, narration, and publishing format, African BD displays an incredible range of variations in form and content at the level of the page that attains yet another novel combination in Aya.

With the exception of political editorial cartoons, BD tends to consist of multiple “frames,” or “panels.” The French term for this page element is case, meaning “box,” because the square is its most typical shape. The outline of a case is called a cadrage, and it separates the case from the negative space between panels. Because the cadrage is a boundary, it is not always visible, but in Aya, the cadrage is usually a thin, black, rounded rectangle that appears hand-drawn. To contextualize this stylistic choice, consider how several comics artists whose works are catalogued by the Africa e Mediterraneo project negotiate the configuration of panels on the page. Each case in Asimba Bathy’s “Kinshasa” is rectangular, at right angles, but they vary in height and width to give a sense of space and perspective in relation to the human scale.57 Samuel Mulokwa’s “Komerera” deploys wide rectangular panels, some of which bleed to the edge of the page and some that dynamically overlap with or are completely inset within others, challenging the reader’s perception of sequence.58 These examples of page designs across contemporary African BD cast the distinctly narrow range of layouts throughout Aya in stark relief.

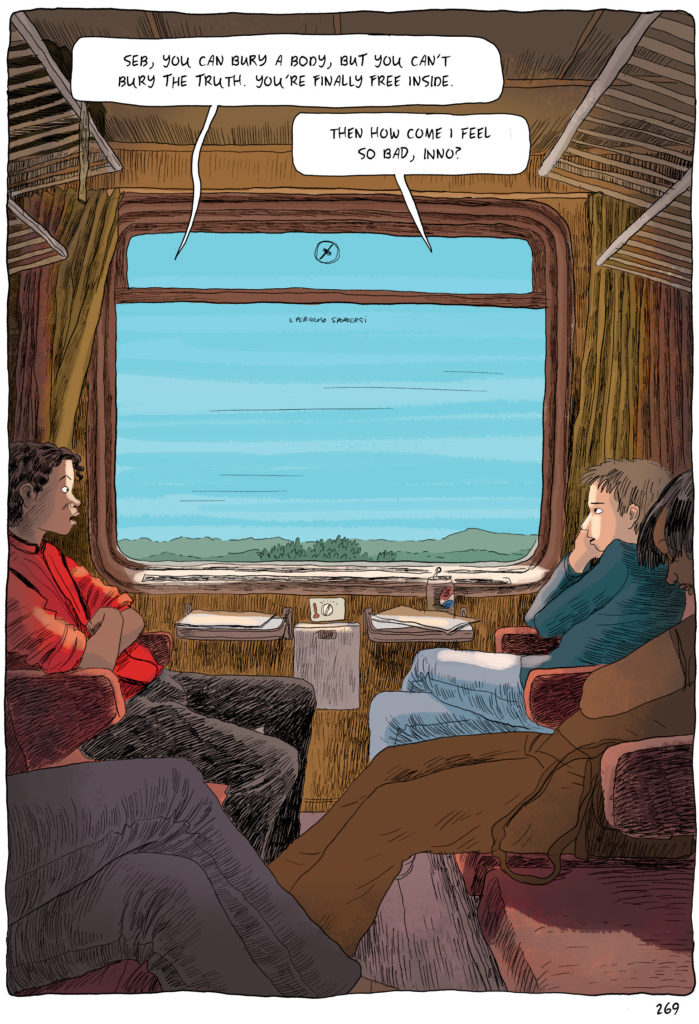

In Aya, the break from a typical layout that consists of six panels on each page to an occasional full-page-sized illustration makes certain scenes especially dramatic. For instance, Oubrerie affords a full page to the scene of Bintou walking toward a luxury hotel that towers over her small figure, but it is the “negative space” of the sky at sunset that demands attention.59 A romantic scene featuring Adjoua and her lover walking on a starlit beach nearly takes up the entire page, but it is abruptly punctuated by a small case that takes up its bottom right corner. In this case, Adjoua reappears in the daytime.60 The new scene takes the place of a supplement that, but for the apparent passage of time, would explain what transpired during the night. Later, a full page depicts the emigrant Inno and his love interest, Sebastien, in facing seats in a compartment on a French train. Their dialogue balloons appear at the top of the case, and they are seated against the window in natural light while other persons on the train are ensconced in shadow.61 The vastness of the image creates the impression that they are traveling in relative silence, with their words floating above them, and the use of color and shadow to differentiate their figures from others contributes to the impression that they are drawn together. In the context of the text as a whole, and in relation to other BD, these page-sized illustrations achieve novel effects.

In addition to his negotiation of page layouts to evoke temporal, spatial, and affective shifts throughout the text, Oubrerie employs hatching and shading as well as color in his illustrations of individual persons, places, and objects. Comics worldwide differ widely in their uses of color, from black-and-white to grayscale to painted or digital palettes, sometimes according to the chromatic options of their publication formats. In Aya, sometimes hues are linked to emotion—green for disgust, red for anger. More often, however, color realistically represents the light in an environment and its reflection off the objects depicted. While ligne claire neutralizes the interaction between color and line, colors only appear fully saturated in Aya in scenes that represent direct sunlight outdoors or artificial lighting overhead, such as office buildings or classrooms. Accordingly, the repertoire of colors conveys variations in the brightness and direction of light, and even diffusion through translucent objects, like sunlight passing through leaves.62

Color makes Abouet’s characters come alive in another fashion: by illustrating the individual nuances of their bodies. In addition to applying color to the task of representing how Black skin tones are diverse, in the aggregate, Abouet and Oubrerie depict them in a range of attire.63 Departing from a norm that makes characters quickly recognizable based on virtual “uniforms” that never change, characters in Aya dress for their social situations. Men employed in corporate offices wear suits and ties to work, but they change in and out of them at home; each of the principal characters wears a variety of dresses, skirts with tank tops, undergarments, jewelry and other accessories, and occasionally, disguises. A scene in which Aya’s cohorts provide a makeover for the much-maligned Isidorine dramatizes the importance of fashion to comic effect.64

Discussing the material culture depicted in the text, Angela Ajayi remarked to Abouet, “the modern (telephones, fancy dresses, and cars from Paris, etc) and the traditional (wearing of traditional waxed cloth-like pagne, etc) seem to coexist well and without much friction . . . you seem to be saying something about the impact of modernity.”65 Abouet agrees; in the first “Ivorian Bonus,” she explains that clothing styles shown in the text are not fixed by identity or determined by historical conditions, per se, but changed at will. One page depicts the friendly face of Adjoua advising readers not to expect different characters to wear the same prints, because “every pattern has a meaning.”66 Like the intricate geometric designs worn by characters whose skin is monochromatically black in the comics drawn by Ivorian artist Amanvi, depictions of the human figure wearing patterned textiles can call attention to the expressivity of the clothed body.67 When multiple patterns are combined, particularly with different colors, it can also create “a completely baroque expression of movement.”68 In relation to examples in contemporary African urban fashion and visual culture, Abouet and Oubrerie’s representations of personal attire from the 1980s are comparatively understated, diminishing the impression that Yop City’s prosperity anticipated the dynamism of the present.

Without any prophetic implications, Oubrerie’s work gives life to Abouet’s vision of an optimistic Côte d’Ivoire where the possibilities are not quite endless, but contained within capacious boundaries. The resourcefulness of everyday life as a source of knowledge emerges through subtle variations in the representation of events and incidental juxtapositions that are affecting, but not jarring. In the concluding section of this discussion, I address how the author positions her account of where her generation of Ivorians fit into the modern world in a similar fashion.

The Romance of Diaspora

Like the issues of textual and visual form, above, the question of precisely how Abouet’s location in diaspora informs her representation of the Ivorian Miracle benefits from considerations of “cosmopolitanism and specificity.”69 Repetti and Naomi Schroth make these qualities central to their treatments of African comics, laying the foundation to extend them into diaspora. First and foremost, we should consider how Abouet conceptualizes movements from Côte d’Ivoire to France—including her own and those of her characters—in relation to the task of historical interpretation entailed by her reconstruction of the Ivorian Miracle as a setting. To that effect, I would argue that Abouet enlists twin narratives of diasporic migration in the task of rendering the Ivorian Miracle as a discrete time and space through which Africans arrive in Europe. One of these movements takes place within the narrative as the journey of a character named Innocent, while the other appears implicitly, but in an equally clear role, as a supplement to the text. The latter—Abouet’s journey—appears as a vignette addressed directly to the reader in Aya’s final “Ivorian Bonus.” In her personal reflection, Abouet recounts how she moved to France without a visa in 1983 in order to rationalize her portrayal of Innocent doing the same in the narrative. Linking these stories of migration in the text lends credence to the proposition that authors interested in making the weaker aspects of their work legible across cultural frames of reference employ intratextual gestures that amount to novelty, while leaving their strong, challenging, potentially contradictory implications exposed to more comprehensive approaches, such as queer theories of the nation and diaspora.

The relation between Abouet’s diasporic authorship and Inno’s homosexuality, which provides the impetus for his decision to emigrate, appears particularly significant in light of recent scholarship exploring the notion of queer diaspora. Gayatri Gopinath introduces this concept to interrogate the interconnectedness of seemingly disparate notions of sexuality and space: “in heteronormative logic the queer is seen as the debased and inadequate copy of the heterosexual, so too is diaspora within nationalist logic positioned as the queer Other of the nation, its inauthentic imitation.”70 An extensive disquisition on the sexual and spatial discourses that overlap on the pages of Aya is beyond the scope of this discussion, but I choose to conclude my analysis of Aya by considering how it broaches the concerns that draw critics to queer diaspora as a strong theory.

In the interest of theorizing its novelty, I regard the internal differentiation within the text that Aya uses to specify the trajectories of its diasporic protagonists as one of the many ways it turns out to be out of step with more radical political gestures that we now know to be possible in culture. In the theoretical sense that employs “queer” as a verb and a descriptor for deconstructing and otherwise interrogating quite unstable foundations of subjectivity in the modern world, including modern cultures’ preoccupation with binaries like the homo/heterosexual distinction, queer diaspora is something Abouet and Oubrerie don’t.71 Works that pursue this task lend credence to the hypothesis that “Queer times require even queerer modalities of thought.”72 Jafari Allen, for instance, concatenates the categories black/queer/diaspora to “argue for the recognition of black/queer/diaspora as at once a caution, a theory, and (most centrally) a work.”73 The theoretical endeavors animated by this understanding, with disparate subjects, e.g., Queering the Color Line, Queering Medieval Genres, etc., serve an urgent critical purpose. In the interest of “Queering West African Literatures,” for example, Stephanie Newell’s analysis draws on the work of Veronique Tadjo, an Ivorian author whose work “illustrates the manner in which ‘queer’ does not refer simply to the promotion of homosexual or lesbian relationships” by liberating female desire from patriarchal conventions, including the binary that structures gender identity.74 Tadjo and other writers in Newell’s study employ strategies more transformative than those of Abouet and Oubrerie, such as écriture feminine, to undermine discursive structures that render women’s sexuality illegible.75 These studies also demonstrate the instrumental value of non-Western locations in providing counternarratives to the terror of having “no framework in which to ask about the origins or development of individual gay [nonheteronormative] identity that is not already structured by an implicit, trans-individual Western project or fantasy of eradicating that identity.”76 Although readers may find that Abouet and Oubrerie’s work presents a novel account of nonheteronormative desire among Africans and a novel treatment of the African presence in Europe, Aya offers no safe harbor from the fundamental dilemmas identified by queer theories, reinforcing the need for strong theories to deal with questions beyond the scope of minor literature.

Innocent’s emigration occurs as a subplot across the last three volumes of Aya. His trajectory from Côte d’Ivoire to France, in which he is alienated at home and enticed by the promise of greater liberties abroad, hews closely to narratives of social mobility articulated in U.S. gay and lesbian liberal politics through the promise “It gets better.” Although Inno and another young man, Albert, have engaged in homoerotic affection back in Yopougon, it was never possible for them to articulate male homosexual identities in the text. In order to rendezvous with Albert at the local lovers’ lane, Inno dresses up in a wig and feminine attire so that other young people meeting under the stars will assume they are a straight couple. Inno’s assumption of a feminine guise rehearses a prominent narrative in what Peter Jackson terms “global queering,” which posits gender insubordination as a traditional analogue to cisgender male homosexuality and maps their relationship onto time and space by situating “underdeveloped” gender insubordination in the “developing” world. These narratives have “often presented a binary opposition between MTF transgenderism, imagined as a site of persistent, premodern, precapitalist ‘tradition,’ and gay forms of male homosexuality, represented as a domain of transgressive, Western-influenced, commodified modernity.”77 The more sophisticated queer critique of modernity Jackson and other critics have since embraced severs the relationship between “traditional transgenders” and modern “global gays,” but Aya posits a singular sexual modernity that Côte d’Ivoire has not yet attained, requiring Inno to emigrate or remain stalled in his—and his nation’s—progress. Indeed, when young Felicité discovers Albert and Inno’s liaisons, she discloses to Aya that she witnessed them “in the bedroom . . . playing . . . PAPA AND MAMAAAA!”78 The infantile register in which Felicité communicates the scandal of their relationship suggests that homosexuality is not impossible, but illegible, in Ivorians’ everyday life. These scenes of misrecognition impel Inno’s pursuit of a cohesive gender and sexual identity in Paris.

Upon his arrival at Charles De Gaulle airport, when the Customs agent asks if he has anything to declare, Inno quips, “Nothing but myself.”79 He obtains a temporary visa—a convenience that many contemporary readers will require Abouet to demystify—and begins his new life. His newfound capacity to embody a cisgender male homosexual identity in France is cast in relief by his budding romance with a white Frenchman, Sebastien. Sebastien is gay, but he and Inno do not consummate their relationship sexually within the text. Rather than sex, the intensity of the friendship that they cultivate by speaking freely with one another deepens the meaning of their shared identification. Whereas Inno’s sexuality was a concrete fact rendered unspeakable in Côte d’Ivoire, once he is in France, his identity accrues significance in discursive form, without being debased in the physical act. Inno’s displacement provides the condition of possibility for an “authentic” experience of being “queer”—an experience that is oxymoronic according to the normative dichotomies that debase homosexuality and diaspora in relation to their dominant counterparts, heterosexuality and the nation. In a pattern that Meg Wesling examines across contemporary theories of queer diaspora, Inno seems to be “called upon to bear witness to the political, material, and intellectual transformations of globalization” as a proper Other to the new subjects imagined by the neoliberal world order.80

Abouet’s supplement to Inno’s narrative is integral to her strategy of employing BD as a mode of historical interpretation. Anticipating that readers will wonder how Inno obtained a visa so easily, she points out that until 1984, the law did not require Ivorians to apply for a visa before entering France.81 Thus, Inno enjoys temporary legal status without incident once he arrives in Paris, just as Abouet did in 1983. In her words, “it was ‘true love’ for Ivory Coast and France, at first . . .Why the divorce?” Further into the recollection, she writes, “Things were easier in Ivory Coast back then. Ivorians didn’t need to go to France or elsewhere to make a better life for themselves.” This reassurance about the Ivorian Miracle underscores that while it was necessary for Inno to emigrate in order to get ahead, due to his urgent personal circumstances, his situation was the exception among trajectories into diaspora rather than the norm—he is queer. The Ivorian Bonus, which stabilizes the meaning of diasporic migration for the characters taking part in the historical events represented within the narrative, offers Inno’s migration as evidence that, according to a critique of queer diaspora shared by Wesling and Jasbir Puar, native homosexuals are not cast out of their homes by retrograde sexual politics in underdeveloped nations, but rather, “the queer subject is also produced through transnational capitalism and the nationalist discourses that exist in tension with it.”82 In the context of Abouet’s apologia, Inno’s exceptional role in the narrative represents the novel example of someone who had to leave Côte d’Ivoire during the Ivorian Miracle precisely when others did not have to, because they could find fulfillment through life in Yop City.

In “strong” theories of queer diaspora, nationalism systematically constructs diaspora as the inadequate and imitative counterpart of the nation just as heteronormativity systematically misrecognizes the participants in a homoerotic relation as inauthentic copies of cisgender heterosexuals. Albert and Inno’s performance as an ersatz heterosexual couple plays out in precisely the way a “strong” queer theory would predict, on the pages of the narrative, but the Ivorian Bonus declares that only aberrant individual circumstances, rather than the structuring logic of nationalism itself, would produce a subordinating relationship between diaspora and the nation. The provocative suggestion here is that the Ivorian Miracle in Aya might corroborate theories of queer diaspora only in part, while frustrating the same theories’ ambition to find out what narratives of diasporic migration really mean. Treatments of the turn toward this particular time and place might call for queer theories and methodologies, but novelty might be a corollary that helps sustain their efficacy in less than systematic terms.

Abouet’s account of the Ivorian Miracle constructs Inno’s emigration as something that was necessary for him, but largely voluntary for others. She insists that her own journey to Paris was involuntary, on a purely personal level, by situating it as part of her childhood. She does not portray her migration satisfying an economic or political need. Instead, she indicates that it appealed to her desires in ancillary ways:

I finally got used to the idea . . . and cheered myself up with the thought that I might at least meet the man of my dreams: Rahan, the beautiful, intelligent, caveman hero of my favorite comic. I thought all men in France had long blond hair, wore little fur skirts, and carried a cutlass. As you can imagine, I was pretty disappointed when I arrived in France.83

Although she found the stories metropolitan France told about itself enticing, young Marguerite was not seduced by them. The disappointment resulting from her initiation into the realities of diaspora turns out to be proportional to her investment in its promises. Neither she nor her characters construe the experience of the Ivorian Miracle wholly in terms of its capacity to prove or invalidate the way diasporic subjects imagine themselves, perhaps because Aya is not a text that takes as its point of departure the presumption that there is any way of knowing the world in its entirety.

Abouet’s journey illustrates that diasporic authorship and BD may not fulfill every wish, but they may still inspire curiosity and offer both pleasant and unpleasant surprises. The concept of novelty can show us how to learn from the limits of our imaginations even as we seek to expand them. Abouet and Oubrerie provide readers with visions of postcolonial Africa and Africans in diaspora that are neither reassuring nor revealing, because the narrative does not pretend to yield up the fates of the parties involved. One of the most instructive gestures in the text is the capacity for characters to return the readers’ gaze, as if to ask what we are looking for. According to one American review: “Eyes, too, prove symbolic, for most everyone walks around sporting wide open, nigh lidless eyes, sometimes looking for all the world like figures in ancient Egyptian tomb paintings, and if somewhat unnatural, this device makes these characters seem endlessly fascinated by the world around them.”84 Given the granular detail in which Abouet and Oubrerie relate developments that are utterly immaterial on the world stage, it is no wonder the constituents of their little utopia are so attentive; it’s as if they do not know what will happen next. Novelty might be an appropriate name for the fleeting moments at which we, too, look up from the grounded determinations that shape our stances toward the entire world to wonder what is happening before our eyes.

Notes

- Massimo Repetti, “African Wave: Specificity and Cosmopolitanism in African Comics,” African Arts 40, no. 2 (2007): 28. ↩

- William Poundstone, Head in the Cloud: Why Knowing Things Still Matters When Facts are So Easy to Look Up (New York: Hatchette, 2016), Chapter 14. ↩

- Robyn Wiegman, “The Times We’re In: Queer Feminist Criticism and the Reparative Turn,” Feminist Theory 15, no. 1 (2014): 7–8. ↩

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press, 2009), 30. ↩

- Kathleen Stewart, “Weak Theory in an Unfinished World,” Journal of Folklore Research 45, no. 1 (2008): 73. ↩

- Queer, in this formulation, is not a metonym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, or other sexual minority experience. Rather, it invokes the deferred, counterhegemonic possibilities that emerge from cultural practices that dwell on desires that are often judged to be insufficiently mature or modern and those that linger on political contingencies whose time has passed. ↩

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 22. ↩

- “The Other Africa: A Comic-Book Return to the Ivory Coast,” Ottawa Citizen, Mar. 25, 2008, C4. ↩

- Alisia Grace Chase, “Preface,” Abouet and Clement Oubrerie, Aya, vol. 1. ↩

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, Or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 144. ↩

- Kathleen Stewart, “Cultural Poesis: The Generativity of Emergent Things,” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, ed. Norman Denzin and Yvonna Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005), 1016. ↩

- Robert Hecht, “The Ivorian Economic ‘Miracle’: What Benefits for Peasant Farmers?” Journal of Modern African Studies 21, no. 1 (1983): 27–30. ↩

- Ibid., 50. ↩

- Wiegman, “The Times We’re In,” 11. ↩

- This section of my discussion reflects on the historic Africa Comics exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2006, which showcased some works that were part of the multi-year, multi-national project Africa e Mediterraneo, from 2001–2007. For a contemporaneous account of the exhibition, see Tony Cox and Farai Chideya’s NPR interview with curator Thelma Golden, “‘Comics’ Exhibit Gathers Africa’s Cartoonists,” News and Notes, National Public Radio, Dec. 6, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6677035. ↩

- Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 144. ↩

- Harry Morgan, “Graphic Shorthand: From Caricature to Narratology in Twentieth-Century Bande Dessinée and Comics,” European Comic Art 1, no. 2 (2009): 35. ↩

- Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie, Aya: Love in Yop City, trans. Helge Dascher (Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2013), 18. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Marc Caplan, How Strange the Change: Language, Temporality, and Narrative Form in Peripheral Modernisms (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2011), 163. ↩

- Angela Ajayi, “Drawing on the Universal in Africa: An Interview with Marguerite Abouet,” Wild River Review, Jan. 2011, http://www.wildriverreview.com/interview /drawing-universal-africa/marguerite-abouet/ajayi-angela.Ajayi, “Drawing on the Universal.” ↩

- Caplan, How Strange the Change, 73. ↩

- Abouet and Oubrerie, Aya, 193. ↩

- Caplan, How Strange the Change, 163. ↩

- Ibid., 237. ↩

- Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading,” 143. ↩

- Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: HarperCollins, 1994). ↩

- Thierry Groensteen, The System of Comics, trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007). ↩

- See, for example, Shazia Rahman, “Cosmopolitanism, Internationalization, and Orientalism: Bharati Mukherjee’s Peritexts,” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 49, no. 4 (2013), and Elliot Ross, “The Dangers of a Single Book Cover: The Acacia Tree Meme and ‘African Literature.’” Africa is a Country, May 7, 2014, http://africasacountry.com/2014/05/the-dangers-of-a-single-book-cover-the-acacia-tree-meme-and-african-literature. ↩

- Guy Lancaster, “Book Review: Aya by Marguerite Abouet; Clément Oubrerie; Helge Dascher,” Callaloo 31, no. 3 (2008): 944. ↩

- Massimo Repetti, “New Comics from Africa,” in Thelma Golden et al., Africa Comics (New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, 2006), 247. ↩

- Repetti, “African Wave,” 22. ↩

- Tayo Fatunla, “Our Roots,” in Golden et al., 194–197. ↩

- Mary Schroth, “Another Way of Looking: African Artists and Comics,” in Golden et al., 256. ↩

- Gail Low, “The Natural Artist: Publishing Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard in Post-War Britain,” Research in African Literatures 37, no. 4 (2006): 15–16. ↩

- Mbembe, On the Postcolony, 144. ↩

- Ibid., 142. ↩

- Okwui Enwezor, “Rapport des forces: African Comics and Their Publics,” in Golden et al., 18. ↩

- Repetti, “New Comics,” 246. ↩

- Sandra Federici and Andrea Reggiani, “Working with the African Comics Artists,” in Golden et al., 26. ↩

- Enwezor, “Rapport des forces,” 17–18. ↩

- Schroth, “Another Way of Looking,” 256. ↩

- Morgan, “Graphic Shorthand,” 22. ↩

- Ibid., 24. ↩

- Ibid., 35. ↩

- Ibid., 32. ↩

- Ibid., 33. ↩

- Ibid., 22. ↩

- Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich, Interview with Marguerite Abouet, The Brown Bookshelf, Jan. 31, 2010, http://thebrownbookshelf.com/2010/01/31/marguerite-abouet/. ↩

- Antonio González, “Comics and the Graphic Novel in Spain and Iberian Galicia,” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 13, no. 5 (2011): 5. ↩

- Repetti, “African Wave,” 27–28. ↩

- Laurence Grove, Comics in French: The European Bande Dessinée in Context (New York: Bergahn Books, 2010), 122. ↩

- On the enduring influence of Hergé and the ligne claire, see Matthew Screech, Masters of the Ninth Art: Bandes Dessinées and Franco-Belgian Identity (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005). ↩

- González, “Comics and the Graphic Novel,” 4–5. ↩

- Repetti, “African Wave,” 23. ↩

- Grove, Comics in French, 65–67, and Conrad Botes, “The Porn Issue,” in Golden et al., 65–67. ↩

- Asimba Bathy, “Kinshasa,” in Golden et al., 60–63. ↩

- Samuel Mulokwa, “Komerera,” in Golden et al., 204–209. ↩

- Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie, Aya of Yop City, vol. 2, trans. Helge Dascher (Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2008), 36. ↩

- Abouet and Oubrerie, Love in Yop City, 147. ↩

- Ibid., 269. ↩

- Sandra Desmazières uses similar colorization to complement Oubrerie’s work in his more recent collaboration with Julie Birmant, a graphics biography of Picasso. Julie Birmant and Clément Oubrerie, Pablo (Paris: Dargaud, 2012). ↩

- Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie, Aya: The Secrets Come Out, vol. 3, trans. Helge Dascher (Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2009), 39. ↩

- Abouet and Oubrerie, Love in Yop City, 259. ↩

- Ajayi, “Drawing on the Universal.” ↩

- Abouet and Oubrerie, Aya, 99. ↩

- Bertin Prosper Amanvi, “Madjalia,” in Golden et al., 48–53. ↩

- Schroth, “Another Way of Looking,” 261. ↩

- Repetti, 16. ↩

- Gayatri Gopinath, Impossible Desires: Queer diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 11. ↩

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 10–11. ↩

- Jasbir Puar, “Queer Times, Queer Assemblages,” Social Text 84-85, nos. 3-4 (2005): 121. ↩

- Jafari Allen, “Black/Queer/diaspora at the Current Conjuncture,” GLQ 18, nos. 2–3 (2012): 214. ↩

- Stephanie Newell, West African Literatures: Ways of Reading (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 199. ↩

- Newell, West African Literatures, 196–199. ↩

- Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet, 41. ↩

- Peter Jackson, “Capitalism and Global Queering: National Markets, Parallels Among Sexual Cultures and Multiple Queer Modernities,” GLQ 13, no. 3 (2009): 359. ↩

- Abouet and Oubrerie, The Secrets Come Out, 71. ↩

- Ibid., 10. ↩

- Meg Wesling, “Why Queer diaspora?” Feminist Review no. 90 (2008): 31. ↩

- Abouet and Oubrerie, Love in Yop City, 334. ↩

- Wesling, “Why Queer diaspora?” 32. ↩

- Abouet and Oubrerie, Love in Yop City, 335. ↩

- Lancaster, “Book Review: Aya,” 943. ↩