On the wall of the Grupo Beta office in Sásabe, a small Mexican border town, is a “map . . . dotted with crosses, one for each body that had been found since the office had been opened. There were dozens upon dozens.”1 The map of the Sonoran Desert that comprises the borderlands between Northern Mexico and Southern Arizona is a warning to potential border crossers about the high risk of death in the area. It emphasizes the hostility not merely of the desert, but the American government’s policies and general attitudes toward migrants entering (either legally or illegally) the United States.

Since the 2016 presidential election, promises for a border wall have been central to the American right’s agenda, asserting the urgent need to secure the nation’s southern border. The continued promise for a wall illustrates an American fixation on protection that disregards the environment and stresses a continued aversion to the bodies of border crossers. Moreover, the Trump administration’s renewed attention toward the southern border ignores the work that has already been done to fortify the border in the form of walls, vehicle barriers, surveillance towers, and the movement of people away from populated areas.2 Crossing the border reduces migrants to waste and wasteful as their journey and experience is only visible and understood through the items that remain.

Using examples from literature and digital art, I examine how the matter of bodies in the borderlands illuminates not only the environment, but the material consequences of policy and rising structures. This article looks at the political and cultural flattening of certain bodies in the United States’ southern borderlands. This flattening is the abstraction of humanity at the center of migrant movement and the reduction of bodies down to what is left behind—effectively erasing the lives, deaths, and stories that led to their position in the first place. By refusing to acknowledge the lived realities of migrants and border dwellers, the region becomes a site of disgust leading to increasingly dangerous immigration policy and more imposing structures as a means of performance rather than protection. I look at Josh Begley’s 2016 digital art piece Fatal Migrations and Roberto Bolaño’s 2004 novel 2666, and I utilize concepts of “waste” and the “environmental other” as defined by Sarah Jaquette Ray, in order to explore how bodies in the borderlands are reduced to political and environmental waste. Taken together these pieces push against the displacement of waste on to certain bodies and work to recenter the narratives of loss that are often erased in favor of increasingly fortified borders.

Begley’s and Bolaño’s works disrupt anti-immigration rhetoric and policy that reduce the borderlands into a monolithic site of danger aimed at the United States. Both artists are concerned with the material reality of the space and the consequences attached to the matter of bodies. Their overlapping interests do not end at the politics of the border but extend to the treatment of bodies in all of their forms (living and dead). Death and its connection to waste are central in both pieces as the artists seek to recover the experiences of those lost in the desert borderlands, either to physical or political violence. Fatal Migrations showcases the places where bodies were recovered in the desert, while 2666 examines how they came to be found in the first place. Importantly, Begley is working from real data collected by the Pima County Coroner’s office, while Bolaño was inspired by events in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico to craft a fictional narrative about the feminicides. Begley is connected with the human element of death, while Bolaños’s approach is much more directed to address the dismissal of hundreds of bodies as literal waste. The works contrast in their approaches but ultimately align to show the continuation of border discourse that encompasses not only the political situation but also the environmental response. Further, their emphasis on recovery at the center of both pieces highlights the multifaceted violences perpetuated by the creation and continuation of the border construct including the environment, politics, and capital.

Despite their differing forms and emphasis on different spaces along the border, both pieces add to the contemporary discussion about increasingly militarized borders and larger barriers. Begley and Bolaño both examine how certain bodies are imbued with social and political meaning and how that meaning is then transferred to the physical space. While both projects work to evoke outrage and empathy for migrants and border dwellers experiencing racial and economic exclusion, they are acknowledging a contradictory discourse that relies upon ideas of disgust and hate. The push for larger structures is propelled by a willful misunderstanding of the border and the borderland’s environment, as well as a refusal to humanize migrants. Begley’s work, published in 2016, is a direct response to the presidential rhetoric about the border and assertions about the wall. Bolaño’s entrance into the discourses about the militarization of the border is more oblique, but directly addresses exploitation in the borderlands and the desert environment. Focusing on the physical environment, both artists highlight its importance not merely as an extensive bioregion, but its weaponization in the name of American sovereignty and place in policy. Through their examinations of death and the materiality of bodies in the desert, both artists grapple with the American political discourse that demands larger structures, both literally and in the form of policy, separating the two countries.

In this article, I examine how bodies in borderlands are treated like waste, specifically focusing on the transition between migrant and illegal immigrant, life and death, use and waste. In both Fatal Migrations and 2666 the environment is a “tool of boundary enforcement and a strategic layer for border crossers.”3 The environment of southern Arizona, on which Begley focuses, and Bolaño’s fictionalized representation of the Chihuahua desert, vary in regard to flora and fauna, but present similar desert-related obstacles. The spaces are hot, dry, and seemingly hostile to those who live in and move through them. I begin by examining the discourse that surrounds ecological waste in the border region and how it is purposefully and insidiously extended to bodies. This leads to a brief discussion of the vibrancy of bodies (both living and dead) via new materialist thought to suggest the interconnectedness of all things as a way of understanding the matter of body in all its forms. I extend this discussion to consider how disgust has manifested itself within the American political imagination as a means of justifying increasingly militarized and fortified borders. I use both Begley and Bolaño’s approach to the border, desert, bodies, and waste as a way of understanding the lasting consequences of placing disgust on to migrant bodies. Furthermore, if the body is figured as literal waste, the consequence of larger barriers is to not only keep out a dangerous and ecologically dangerous other, but to erase their bodies and movement entirely.

Environmental Waste

All along the border in southern Arizona are posters that warn migrants about the dangers of entering the United States through the desert. Posters by the non-profit migrant aid group Humane Borders read “No Hay Suficiente Agua! No Vale La Pena!” (There’s not enough water! It’s not worth it!). The posters warn border crossers about the risks of moving into the desert, but also position the land as isolated and treacherous. The natural world is more than just a form of passage for border crossers; it is also a policing tool that allows the US government to evade responsibility for the amount of deaths happening on US soil every year.4 As Jason de León writes in The Land of Open Graves, “The Border Patrol disguises the impact of its current enforcement policy by mobilizing a combination of sterilized discourse, redirected blame, and ‘natural’ environmental processes that erase evidence of what happens in the most remote parts of southern Arizona.”5 The environment then becomes a protected and policed space that relies on the exclusion of certain “disgusting bodies.”6

The reduction of bodies to waste is part of the American colonial legacies that reduced colonized bodies to dirty, disgusting, and wasteful as a means of control. American bodies were figured as “closed” and “ascetic” while the colonized bodies were “open” and “groteseque.”7 This diminishment is often linked to hygienic practices and used to dismiss the humanity of colonized subjects.8 In this way, the body of the “other” is not only disgusting, but dangerous to the environment and American health. This understanding of dangerous and disgusting bodies is especially salient where America is confronted with a racialized other. Border crossers and dwellers are vilified for wasteful and “leaky” bodies that are only visible through the waste left behind. The “corporeal presence of undocumented immigrants in border-protected areas is repeatedly associated with defiling and contaminating nature.”9 The movement of people through the border is only visible through that which is discarded, and American colonial logic relies on dismissal of non-Western bodies on the grounds of uncleanliness. Moreover, the focus on the corporeal body of border crossers is grounds for exclusion as the “interest in bodily leakages derives from their role in Western conceptualizations of subject formation”; they are “requirements of civility, rationality, and therefore inclusion in the body politic.”10 This understanding of the body of “others” makes them a continuous threat to the natural world, but also the American body politic.

Unclean bodies propel border discourse through the multiple threats they represent to the environment, national security, and ideas of disgust. As Sarah Jaquette Ray posits in The Environmental Other, “disgusts shapes mainstream environmental discourse . . . by describing which kinds of bodies and bodily relations to the environment are ecologically ‘good’ as well as which kinds of bodies are ecologically ‘other.’”11 For Ray, environmental disgust is inextricably linked to the movement of bodies through particular environments and the ways bodies both take in and push against their surroundings. Those who pose a threat to the environment, through various toxicities, are “measured at the level of the body.”12 This approach to disgust functions at the individual level, meaning that certain bodies are rendered disgusting, while toxicity is the product of disgust on a larger scale. Disgust through the form of trash, in the case of the migrant, is reflected back onto the bodies that move through the nature of the border region.

The use of nature preserves and national parks along the US-Mexico borderlands stresses the importance of a clean and waste-free wilderness. Importantly, “the protection of the land came at the cost of stripping indigenous and Mexican-American people from their rights to land.”13 The presentation of a clean environment along the border gestures to the US colonial legacy and the continued oppression and violence of the border region. Not only do these measures present an environment worthy of preservation, it emphasizes the place of the environment in immigration policy. Ideas of disgust and environmental protection are mobilized in the creation of governmental policy to invoke “anti-immigration not just as a national security imperative, but an ecological one. That is, immigrants are trespassing protected ecosystems and wildernesses, not just national boundaries.”14 By pairing matters of national security to the environment, US governmental policy has the power to utilize disgust against a racialized other as more than just an immigrant, but also a threat the health and purity of nation. Essentially, the state of “nature” along the border renders those sites “productive sites for delimiting and naturalizing the national body.”15 Movement into the nation is elevated to a national security threat that compromises the entire system—environmental, political, and affective.

By militarizing and weaponizing the borderlands environment, the US government relies heavily on environmental discourse to maintain national purity in its many forms. Parks and protected landscapes like Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, and Big Bend National Park all line the border adding an additional layer of criminality as migrants move through these landscapes. These parks are used to challenge the extent of sovereignty and create “a no man’s land where sheer physical survival is a feat and often a miracle, a place where rule of law is momentarily suspended, where the fate of those who wander is left to the natural elements and the harsh terrain.”16 The maintence of parks along the border shows the US government’s reliance upon both sovereignty and environmental discourse to erase and criminalize migrants. These parks are an essential part of border policing by pushing migrants into isolated and dangerous landscapes, vilifying their movement through claims of illegal park entry, and criminalizing any waste they leave behind. Blame is placed on those who “move through the desert wilderness” as “immigrants are presumed not to care about protecting it.”17 In using the park as a form of passage, migrants are thought to move carelessly, leaving behind objects no longer necessary for their journey and trampling indigenous flora. Public discourse has long vilified migrant movement as environmentally dangerous as a 2003 article from Tucson Citizen states that “more trashed sites are likely until illegal immigrants stop coming over the border or start cleaning up after themselves.”18 This aversion to illegitimate objects is read on to every aspect of the migrant experience, including the placement of water by migrant aid groups. A leaked video in January of 2018 showed Border Patrol agents destroying water jugs saying, “picking up the trash that somebody left on the trail.”19 Migrant movement is typically only visible through the objects they leave behind, making their journeys through preserved environments environmentally dangerous not only to a pristine wilderness, but the country.20 Migrants are seen to move carelessly, and any waste in the form of food wrappers, water jugs, and even campfires are reduced to an ecological threat. Ultimately, the remains of migrant journeys are used to rationalized disgust aimed at migrant bodies, as “trash makes visible the invisible movement of people through the borderland.”21 While the bodies of the migrants have moved through the environment, the supplies necessary for that movement are left behind as waste and as reminders of not only those who have moved but also the toxicity their bodies represent.

Ray’s examination of disgust in the borderlands gestures to the contemporary environmental discourse in the region as intertwined with the politics of migration and American sovereignty. While I take the importance of her contribution, it does not confront the reality that the waste in the desert borderlands is not limited to materials but includes the very bodies associated with the region. The body’s association with waste and toxicity continues even after death, figuring the migrant body as a persistent ecological hazard. Already reduced to the trash they leave behind, migrants’ bodies are associated with waste even after death—figuring them as environmental hazards. Certain bodies have access to the desert environment and protected landscapes. More specifically, white bodies are allowed to hike and move through protected landscapes, but racialized migrants are called into question.22 The presence and persistence of border patrol in the region is also exempt from environmental scrutiny as they exist to fortify the border; any waste they produce or damage they do is a natural consequence of security.23 However, this privileging does not address the body as waste (regardless of the body—white or racialized—it begins to decay). This absence calls into question not only how we understand bodies decaying in the desert but also whose bodies are visible and recoverable.

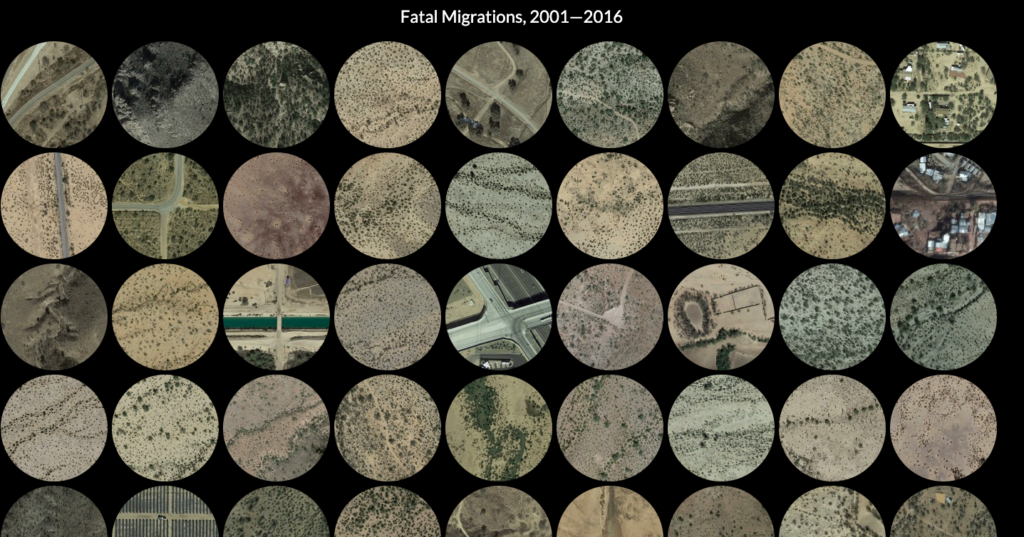

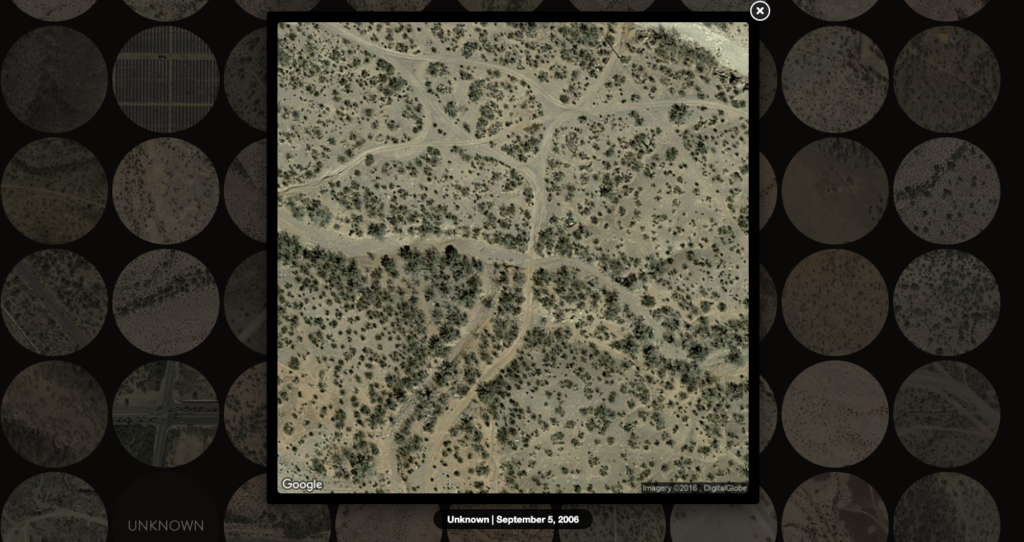

In representing the border, Josh Begley’s Fatal Migrations offers “Some of The Places People Died While Trying to Cross the Border.”24 The piece, comprised of 2,600 circles, is the “interactive visualization . . . [of] the known location of someone’s death.” 25 The piece centers on land on the Arizona side of the US-Mexico border where migrants die crossing the desert every single year.26 In pushing against the flattening discourses of the border region, Belgey’s focus on migrant death intervenes in the use of the border region as a monolithic political talking point. The emphasis on the environment through visual images gestures to the complexity of the region that is both environmental and political. Begley’s interactive piece calls forth the multiple intersections of ecology, affect, and the materiality both of the desert and the bodies left behind.

In working through these intersections, Begley leaves out the bodies of border crossers, stressing the erasure of their experiences alongside their material body. Begley shows the places where migrants have died without relying on gruesome images that depict death, but rather focusing on how the environment and political rhetoric work in tandem to remove the reality of people in the region. Begley highlights the importance of each individual body found in the desert by providing each person with a bubble that shows an image of where their bodies were recovered from google maps. The viewer is encouraged to click on each circle which states the name of the victim at the bottom. Begley’s use of interactivity implicates the user in the maintenance of the border. Each click pulls up a different place, though the desert blurs together quickly as the user scrolls over the circles. The display emphasizes the vastness of the desert and the very real danger it presents for those who might get lost or merely do not have sufficient supplies to cross. Begley foregrounds the danger most migrants face when they enter the space between the United States and Mexico, which is not just the border patrol and harmful, racist, rhetoric that stand in their way.

Each image works against the anonymity of many migrants by attaching a name and a date when the body was recovered. The piece is not searchable and relies on users to scroll, click, and take their time with each photograph. Even those who died in the desert without a specific location attached are represented through a black circle with white writing stating “Unknown.” Conversely, several circles do not have a name, just a date and an image of where the body was found. Begley’s piece is simultaneously art, catalogue, and memorial showing the vastness and urgency of migrant death in the desert. Using digital images of the land, Begley stresses that the border is a political construct placed upon the environment. The decay of bodies in the borderlands suggests the reintegration of bodies into the environment and illuminates the connectivity of all matter through all things. By omitting the bodies, Begley is showing how matter not only moves through environmental systems, but within discourse. As Jane Bennett suggests in Vibrant Matter, all matter has the ability to act and act upon the world that surrounds it regardless of perceived liveliness. She suggests that we must examine a “vibrant materiality that runs alongside and inside humans to see how analyses of political events might change if we gave the force of things more due.”27 Bennett’s contentions about recognizing the potential of matter emphasizes that the “status of the shared materiality of all things is elevated.”28 Giving “things” their due means recognizing their force beyond the binaries of alive and dead to see the possibilities in all things and the interconnection of everything. This does not mean the reduction of bodies to things, but rather a way of recognizing all things to account for the responsibility we hold for our entwined position. Christina Holmes writes about a “web of relations” that accounts for “other humans and the more-than-human world” as a way of recognizing the continuous influence that matter (all matter) is both impacted and impacting the world.29 Understanding bodies, both living and dead, as persistent and vibrant matters places it directly within a larger web of relations that allows for those bodies to be memorialized, mourned, and remembered. As such, the bodies that are both missing and represented within Fatal Migrations are continuous and have a lively persistence that demands recognition and continuously interacts with the human and non-human worlds. Moreover, accounting for the vibrancy of all bodies demands recognition for how they are part of discourses about the borderlands and why they are continuously dismissed alongside the trash that makes migrant movement visible. Accounting for the matter of bodies in Fatal Migrations shows how they are vibrant in their absence, suggesting the importance of all migrants within larger political, economic, and cultural systems.

A live body is more than just matter, but as Begley suggests, the harshness of the desert is relentless on all matter regardless of motivation. The images Begley uses do not show the physical walls or fences that have long delineated the border but stresses the sprawling desert as an essential piece of bordering. The absence of the border fence suggests that American immigration policies such as Prevention through Deterrence (1944) are just as successful in erasing the realities of migration.30 The danger is more persistent to migrants than a looming but scalable wall. By understanding the border region as a complex ecosystem of hostile environment and political barriers, Begley is calling attention to the materiality of the bodies left behind in the region. Isolated areas along southern Arizona are absent of structures, people, or aid, making the desert a hostile tool that reduces the migrant experience into nothingness. All that remains, as Begley suggests through each picture, is the vibrancy of the bodies. Or understood more broadly, the acknowledgment that someone died in that area, and in doing so, shifted the space. Every body tells an important story worth reclaiming. Begley’s Fatal Migrations works to recover these narratives by illustrating that those lost in the desert borderlands have continued to impact the world that surrounds them, through their bodily reintroduction to the environment and their ability to produce an emotional response. The bodily waste of border crossers is vibrant as it continuously acts on the world, including through the computer screen, regardless of conventional ideas of liveliness. This vibrancy carries through the bodies’ reintroduction to the environment, and more importantly in Begley’s project, into the way the American public views dead bodies in the borderlands. Caught in a continuous web of relations, the people represented in Fatal Migrations exhibit vibrancy as the effect they have does not end with their deaths at the hand of inhumane border policy but becomes part of larger discourses about the border. Read alongside Ray, Begley’s project stresses the need for attention in the borderlands, while working to highlight the importance of bodies that are dismissed in the name of sovereignty. The difficult choice to cross the border is reduced to the spread of non-American waste.

Begley’s work not only re-centers migrant narratives as ecological and political but also stresses the unnatural nature of a political divide more broadly. As Jessica Autcher writes in “Border Monuments: Memory, Counter-Memory, and (b)Ordering Practices along the US-Mexico Border”, the construction of the border is an attempt to solidify nationhood and sovereignty. The border is an intentional disruption meant to partition the United States from Mexico and the environment from its natural state. Autcher writes, “Before the fence, there is just desert, brush, and land. After the fence there are citizens, ownership, geography, territory, governance, and enforcement.”31 Autcher, like Begley, emphasizes how the artifice of the border has led to large numbers of deaths at the hands of the state. Fatal Migrations highlights this by showing the land in individual circles and creating a dizzying effect of not knowing where the bodies were recovered. The “borderlands” encompasses a large area, nearly 2,000 miles, but by focusing on desert that looks nearly identical in every image, Begley is highlighting how a line in the sand costs thousands of lives. By scrolling through the piece, the viewer experiences visual markers acknowledging how migrants easily get lost and how fragile life is in a hostile environment. The absent bodies in Begley’s piece allow for a reimagining of the missing narrative that led to the migrants’ deaths. Waste is tangential to Begley’s art, but his focus on the migrant body brings it to the forefront when examining the borderlands—a site of death for thousands of migrants. Belgey’s focus on death in the borderlands allows us to understand how waste and wastefulness are placed upon bodies that move across the border. His emphasis on the environment demonstrates how all bodies are caught in a web of relations that includes and interacts with the non-human world. Each image is both a tribute to the person lost and a reminder of the body’s reduction to waste in a natural space made unnatural by a political boundary.

“The Inertia of the Festering Place Itself”

Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, a novel in five parts, culminates in Santa Teresa, Mexico, a fictional city along the United States-Mexico border. While the plots of each part differ, the one common thread throughout each narrative is the murders of thousands of women in Santa Teresa. A passing detail in the background of the first stories, becomes central by the fourth part, “The Part About the Crimes.” Beginning in 1993 and concluding in 1997, Bolaño’s approach to the murders mimics the real-life discourse that surrounded the feminicides in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico during the same time. The murders, both central to the plot and pushed repeatedly into the background, show how a lack of urgency amounts to an unacknowledged crisis. “The Part about the Crimes” blurs the lines of fiction and reality by extrapolating upon real events through made-up names, circumstances, and characters. By creating Santa Teresa, Mexico as a stand-in for Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, Bolaño layers the facts from the murders with a larger story, creating a mix of “what he knew and what he imagined.”32 The result is a haunting narrative of violence where the victims never speak but are constantly present. 2666 is both focused on reclaiming the voices of hundreds of women who were needlessly killed in the borderlands and recognizing the systems that silenced their deaths in the first place. “The Part About the Crimes” has several different characters who move in and out of their interactions with the murders, both acknowledging and ignoring their scale and urgency. While it is a bound section, it reads as a series of interconnected vignettes that tell the story of continued violence from the authorities, corporations, politicians, and the community. Bolaño starts many of the sections with the name of the victim (if possible) and the circumstances in which her body was discovered. Throughout “The Part About the Crimes” Bolaño centers not on border politics, but loss of lives in the border region. Bolaño makes it clear that the murders are the consequences of the intersections of the border, capitalism, and the environment. Despite not directly addressing the political rhetoric of the militarization of the border, Bolaño engages with the politics of the borderlands specifically through death.

In attempting to reclaim the voices of victims, Bolaño begins “The Part About the Crimes” in a vacant lot. The body was found “in Colonia Las Flores. She was dressed in white long-sleeved T-shirt and a yellow knee-length skirt, a size too big. Some children playing in the lot found her and told their parents.”33 This discovery establishes the narratives that follow as part of a chronology of the murders. The girl is identified as, “Esperanza Gómez Saldaña”, and her death is cursorily investigated before her body is “put . . . away in a freezer” without further investigation.34 Her murder remains unsolved, marking the beginning of the feminicides Bolaño discusses throughout the section. Esperanza Gómez Saldaña

heads the list. Although surely there were other girls and women who died in 1992. Other girls and women who didn’t make it onto the list or were never found, who were buried in unmarked graves in the desert and whose ashes were scattered in the middle of the night, when not even the person scattering them knew where he was.35

By beginning the narrative with an arbitrary indication, Bolaño acknowledges the murders as the consequence of historical violence and border politics. Few murders are solved throughout the narrative. Most of the cases are closed without resolution or merely forgotten in pursuit of other crimes.

Esperanza Gómez Saldaña’s body is carelessly discarded in a vacant lot, reducing it to waste. Esperanza’s is the first body found in 1993, but she is not the last to be found in a vacant lot. Throughout the narrative, bodies are found in desolate areas or directly alongside garbage to show their lack of worth in Mexican society. The murdered bodies are almost exclusively women, highlighting the disposability of femininity. The bodies of women are found in dumps, along roads, and often in view of maquiladoras. In May, “a dead woman was found in a dump between Colonia Las Flores and the General Sepúlveda industrial park. In the complex stood the buildings of four maquiladoras where household appliances were assembled.”36 While not all of the women fit a particular profile, as Bolaño is sure to point out, the majority of the victims have some association with the subassembly plants that line the border. The maquiladora system is comprised of largely foreign- and US-owned companies that have played a pivotal role in the creation and continuation of poverty along the border.37 Bolaño’s narrative does not focus explicitly on the maquiladora system, but its presence in the majority of the murder cases points the connection between foreign capital, domestic exploitation, and death. Often, women went missing after their shifts at the maquiladora as “the area around the maquiladora was deserted and dangerous, best crossed in a car and not by bus and then on foot since the factory was at least a mile from the nearest bus stop”38 The conditions for reaching the maquiladora daily may be dangerous, but they provide steady work to thousands of women who pour into borders cities yearly.39

The maquiladora system is crucial in perpetuating ideas of the borderlands as unclean and toxic. Environmental arguments about the implementation of NAFTA focused not on the damage large subassembly plants would have the local environment but on the bodies of workers turned migrants. The logic followed that in attracting more people to the border, more people would take the steps to cross into the United States, and those bodies are “the real source of pollution.”40 Workers are understood through their association to the plants and “border pollution does not stay put.”41 The environmental focus on NAFTA shows “traditional American stereotyping of Mexicans as dirty, unhygienic, and self-soiling; it also made the prospects of uncontrolled immigration seem both naturally inevitable and consequently more threatening.”42 By placing bodies in the view of maquiladoras, the border, and in dumps, Bolaño is gesturing to the reduction of some bodies to waste through political and economic structures. The matter of the body cannot exist outside of these structures, but rather is understood and flattened through them.

Throughout “The Part about the Crimes” Bolaño stresses the refusal to acknowledge bodies and the murder cases. As characters interact with the various cases, other deaths occur completely in the background. Police officers stand around joking and laughing as, “A man dressed in white, but wearing jeans, pushed a stretcher. On the stretcher, covered in a gray plastic sheet, lay the body of Emilia Mena Mena. Nobody noticed.”43 The narrative focus on the man’s jeans and the policeman’s laughter show how the death of another woman is so commonplace it fades into the background. Bolaño explains the death of Emilia Mena Mena in the next section. She was found in a dump that “didn’t have a formal name, because it wasn’t supposed to be there, but it had an informal name: it was called El Chile.”44 Created in the desert that surrounds the city and on the outskirts of the maquiladora plants, El Chile becomes a center for disgust. The dump’s reoccurrence in the narrative aligns with the deaths of hundreds of women. As more waste accumulates, more women die. By placing the bodies in an unplanned dump, Bolaño is suggesting the equation of the materiality of bodies to the materiality of literal waste. Given the proximity of the border and the maquiladoras, the waste associated with bodies is highlighted through the dump’s appearance and seeming persistence throughout the novel. The authorities do little to prevent the accumulation of waste in the form of garbage and bodies. In many ways, the bodies recovered there have never been treated as more than the waste that surrounds them. Like Ray’s assertions about the transference of waste left behind in the desert, the bodies placement amongst garbage sends the same message. The result is what Zygmunt Bauman articulates in Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts: “’human waste’ or, more correctly, wasted humans” which are “the inevitable outcome of modernization.”45 As Bauman suggests, the place of humans in waste is part of the uneven process of modernization and one that reduces humans to waste within a capitalist system. In Santa Teresa, El Chile sprawls as a direct result of the economic outcomes of the border—most clearly, the maquiladoras and NAFTA. The disgust generated toward El Chile and the women within is not aimed at system or even those who commit murder, but the bodies themselves.

Dumps are not the only site where bodies are recovered. Bolaño’s positioning of the environment mirrors that of Begley’s approach as he acknowledges the importance of the barren desert that accounts for large portions of the borderlands. One body is “found in the desert, a few yards from the highway between Santa Teresa and Villaviciosa. The body, which was in an advanced state of decomposition, was facedown . . . . The killer or killers didn’t bother to dig a grave. Nor did they bother to venture too far into the desert. They just dragged the body a few yards and left it there.”46 The natural elements (i.e. heat and animal interference) prove graves unnecessary, as the environment works to hide any incriminating evidence. The desert not only covers the crime but reintegrates the body into the larger ecosystem. Refusing to bury the body suggests a refusal of dignity for the murder victim and hatred of her humanity. After recovering the body, it was impossible to “establish the cause of death, alluding vaguely to the possibility of strangulation, but it did confirm that the body had been in the desert for at least seven days and no longer than one month.”47 The desert acts upon the bodies discarded there, refusing reduction to a passive background, but rather becoming an active agent in boundary enforcement.48 Like many of the other cases throughout the section, this one goes unsolved as the investigator assigned to the case is encouraged to “focus on the specific case under investigation” once realizing the identification found with the body does not match the victim.49 The constant deflection of investigation throughout the novel illustrates the bureaucracy that stands in the way of solving any cases, allowing for more and more deaths. No case is solved without institutional support and access to the proper resources. While Bolaño is concerned with vilifying the systems in place that perpetuated the deaths of hundreds of women (i.e. global capitalism and insidious bureaucracy) he does not position many of the investigators as blameless characters. Rather, nearly all of his characters do nothing to question the systems that surround them or the deaths those system perpetuate.

The desert occupies a strange liminal space in 2666. It is a site of extreme violence and death, and its beauty is one of the most hypnotic aspects of the novel. In the first part of the novel, “The Part About the Critics,” Bolaño pulls back from the harshness of the space claiming, “hostile wasn’t the word, an environment whose language they refused to recognize, an environment that existed on some parallel plane where they couldn’t make their presence felt, imprint themselves, unless they raised their voices, unless they argued.”50 Bolaño uses the idea of “xerophillia,” or the “condition of being adapted to and expressing a fondness for dry, arid places,” to explore that landscape as simultaneously beautiful and strange in its capabilities.51 The desert is unrecognizable and incomprehensible to outsiders but equally impossible to overcome to natives. In the first two sections of the book, the desert landscape is kept at bay through an outsiders’ view of it as hostile and insurmountable. It looms in the background of each narrative, not just a backdrop for action, but an environment that holds secrets and resentment towards the humans that live on the land. While “The Part About the Crimes” focuses on the local murders, it also acknowledges those who attempt to migrate across the desert landscape at least twice. In attempt to solve one of the many murders, the police accused a Salvadorean migrant who spent “two weeks in the cells of Police Precinct #3.”52 Once released he was a “broken man. A little later he crossed the border with a pollero . . . he got lost in the desert and after walking for three days, he made it to Patagonia, badly dehydrated. . . . he was picked up by the sheriff and spent the day in jail and then was sent to a hospital . . . [where] he [died] in peace”53 The Salvadorean migrant’s death brings the desert that surrounds Santa Teresa closer, reminding the reader that not only is the city deadly but so too is desert that surrounds it. In this way, the citizens of Santa Teresa are caught in a precarious set of overlapping violences that insure they have nowhere to turn. Based on Chihuahua desert that surrounds Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, the desert borderlands is a deadly space, environmentally, politically, and culturally. The Salvadorean migrant’s death, like those captured in Fatal Migrants, happens quietly and is not mourned or even acknowledged again.

El Chile and other dumping sites throughout “The Part About the Crimes” embody the political backdrop of the border region. The dumps literalize the placement of those who inhabit the liminal space of the borderlands, bringing forth disgust. The transference from garbage as waste to bodies as waste shows how disgust is placed upon those who inhabit or cross the intersection of the two countries. El Chile proves impossible to remove as “work to get rid of the illegal dump . . . was permanently halted. A reporter from La Tribunana de Santa Teresa who was covering the relocation or demolition of the dump said he’d never seen so much chaos in his life . . . it came from the inertia of the festering place itself.”54 The dump takes on a life of its own as efforts to do anything about it are continuously thwarted, allowing officials to let the garbage stay and continue to rot. The abandonment of removing El Chile comes approximately halfway through the narrative and shows how officials found it easier to let go any attempt at intervention in favor of the path of least resistance. The mounting of waste mirrors the bodies that accumulate throughout the narrative. More bodies are found in El Chile afterward; it remains a site of disgust and waste, allowed to grow through a continuous refusal to actually find the source of the problem. Bolaño’s equation of the murders to the dump is essential in demanding recognition for the women who have been discarded there, pushing against the reduction of bodies to waste.

The final murder in the section ends on a note of resignation and gestures to the continuation of feminicide further into Mexico. In December 1997, the last body “wasn’t found on the western edge of the city but on the eastern edge, by the dirt road that runs along the border and forks and vanishes when it reaches the first mountains and steep passes.”55 The woman’s body is still recovered in view of the border, but rather than leading to the desert, it leads into the mountains. The move from west to east gestures to the continuation of the crisis in the rest of Mexico. There is no resolution only the spread of continued violence throughout the rest of the country. The suggestion of continued and spreading violence is juxtaposed by the celebration that masks the darkness of the streets “like black holes, and the laughter that came from who knows where was the only sign, the only beacon that kept residents and strangers from getting lost.”56 The city’s movement forward comes at the cost of continued death on political, social, and economic levels. More specifically, the price of progress in Santa Teresa is the deaths of hundreds of women for the success of foreign-owned companies. As the conditions in Santa Teresa remain, so too do the deaths of a vulnerable population.

From Waste to Walls

Bolaño and Begley both point to the refusal to acknowledge the violence enacted upon marginalized bodies in the border region and the importance of recovering each person. The erasure of peoples in the region is a continuation of violence and part of a global move to solidify borders. This solidification creates, as Todd Miller writes in Empire of Borders, “never-ending battlescapes” that lead to continuous escalation and fortification.57 The violence of the US-Mexico border is not exceptional in its creation, but the silence that surrounds the loss of life in the region allows for its continuation. Importantly, this silence is not restricted to movement across the border but extends to the maquiladora systems as a site of political, environmental, and economic strain. The result, as both Bolaño and Begley show, is mass amounts of deaths for vulnerable populations that go unnoticed on local, national, and global scales. Feminicide and migrant deaths are allowed to continue simply through the refusal to acknowledge their existence. US immigration and economic policy has thrived on the silences that surround death in the borderlands, instead insisting that the problem is environmental or social. In essence, migrants are aware of the risks of entering the desert of southern Arizona just as women should know better than to walk home alone at night. Begley and Bolaño look to the bodies of border crossers and dwellers as a means of reasserting the importance of acknowledging the people who have died as a direct consequence of economic and political decisions.

By positioning the bodies that reside along or cross the border as an ecological danger, anti-immigration policy relies on discourses of purity and by extension whiteness. The nature of the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument is a pure, natural ideal, a reflection of the rest of the nation as untainted and organized around a specific type of Americanness. When “disgusting” bodies cross borders they “threaten the pure bodies; such bodies can only be imagined as pure by the perpetual restaging of this fantasy and violation.”58 American purity is born out of contrast with the surrounding nations. Importantly, this emphasis on purity furthers the “belief that the Mexican immigrant was the real source of pollution” reducing not only migrants, but border dwellers to pollution.59 The movement of illicit and dirty bodies, is very literally, the “unwanted movement . . . by which the border environment became comprehensible to the American public.”60 As Begley and Bolaño show, the realities of the border are only visible through the movement of bodies perceived as threatening and environmentally dangerous.

The resulting militarization of the United States’ southern border has taken a variety of forms including policy, increased surveillance, and most recently, increased attention on physical barriers.61 The turn to walls and walling out people and nations calls into question not only the materiality of the wall, but the practice of walling. The wall is the move from passive, and relatively quiet, immigration policy to performative action aimed at a racialized border, its citizens, and ideas of waste. As Wendy Brown describes in her book Walled States, Walled Sovereignty, border walls are “not built as defense against potential attacks by other sovereigns” rather “these walls target nonstate transnational actors—individuals, groups, movements, organizations and industries.”62 The rhetoric that surrounds the border wall is not so much about walling out the Mexican nation (though that is gets lumped in very easily), but preventing specific, threatening, bodies from impinging on the borders. Donald Trump’s campaign and presidency has long been aimed at people crossing the border calling Mexicans “drug dealers, criminals, rapists.”63 It’s important to remember that many migrants crossing the border are not coming from Mexico, many are from Central and South America.64 However, by focusing on certain bodies, anti-immigration discourses can emphasize the requirements for inclusion in the body politic. Looking at bodies as waste and wasteful excludes any leaky or unclean bodies from gaining entrance to the United States. In excluding unclean bodies, walls are about the performance and maintenance of sovereignty as it applies to citizens. The creation of walls is an extension and assertion of this sovereignty in action as “new walls function theatrically, projecting power and efficaciousness that they do not and cannot actually exercise.”65 Further, calls for a wall along the United States’ southern border are often about ideas of American safety. In a January 2020 tweet, Donald Trump tweeted, “The powerful Trump Wall is replacing porous, useless, and ineffective barriers in high traffic areas requested by Border Patrol. Illegal crossings are dropping as more and more Wall is completed! #BuildTheWall.”66 The previous wall is deemed “useless” as a means of justification for a new wall that will keep people out. The wall is directed at certain bodies and created to keep a white American public safe. As Brown asserts, “Walls built around political entities cannot block out without shutting in, cannot secure without making securitization a way of life, cannot define an external ‘they’ without producing a reactionary ‘we,’ even as they also undermine the basis of that distinction.”67 Walls are built with the intent to shut out, but in reality, work to bind and keep in a particular population. They solidify the dichotomy between who has legitimate access to the nation and who is worth shutting out.

Brown’s focus on the maintenance of sovereignty through walls points to the dismissal of migrant bodies and lasting effects of understanding the border as a site of disgust. Throughout Sarah Ahmed’s Cultural Politics of Emotion, she writes about the ways in which populations bind emotionally and affectively. Her consideration of borders accounts for a collective mentality that is an important social tool in understanding who we identify with or against. Borders are the nation’s defense, but they are “like skin; they are soft, weak, porous and easily shaped or even bruised by the proximity of others.”68 Borders are particularly soft areas as they are not only where the nation meets a racialized other, but a necessary point of entry for goods, capital, and labor. After all, “Porous borders, the story goes, permit the flow of drugs, crime, and terror into a civilized nation whose only crime is to have been too prosperous, generous, tolerant, open, and free.”69 The nation exposes itself to dangerous bodies at its borders. Policies like Prevention through Deterrence have deliberately endangered migrants as a means of national security that has continuously solidified into larger structures. The result, regardless of what the American right might suggest, is not a safer nation, but deadlier conditions for all peoples moving across borders. Binding the nation against an “invading” migrant caravan as Donald Trump declared in November of 2018 pushes people into deliberate danger to erase not only their lives, but the violence done against them.70 Willfully pushing migrants into the desert is the continuation of violent legacies in the borderlands that asserts lives in the borderlands are not worth saving, protecting, or even acknowledging.

Fatal Migrations and 2666 both predate the gradual building of the Trump administration’s wall on the US-Mexico border, but both works illustrate the escalation of fortification at the expense of certain bodies. In other words, both works illustrate how the silence that surrounds deaths is necessary for the continuation of the border itself. Begley and Bolaño both illustrate the need for recovery of each death as a means of resistance and recognition for the lasting legacies of borders. Importantly, the move to build a physical wall along border is just the most visible way the US has vilified peoples moving across borders. Immigration policy has steadily shifted toward increasingly inhumane policy and conditions not only for border crossers, but asylum seekers and refugees. The Trump administration has moved to decrease the number of refugees the United States takes from 30,000 to 18,000 in the year 2020.71 Importantly, this accounts for the total refugees entering the United States, not only those attempting to enter through the US-Mexico border. Refugees and asylum seekers have a right to seek entry into the country through legal means, but policies like Remain in Mexico have increasingly vilified their efforts and forced them into dangerous circumstances. Starting in November 2019, the Trump administration’s Remain in Mexico policy made the standards for applying for asylum much more rigorous and mandated that applicants wait on the Mexican side of the border as their case made its way through the courts.72 However, the refusal of refugees, policies like Prevention through Deterrence, the Trump administration’s Remain in Mexico policy, and the construction of the wall across the border demonstrate a solidification of all borders against non-citizens. The continued walling of the southern border is not just aimed at Mexico or migrants moving across the desert, but all peoples attempting to make their way to and into the United States.

As of February 2020, the government has waived forty-one laws to build the border wall, many of them environmental.73 In the first seven months of 2020, 120 migrant bodies had been recovered in southern Arizona.74 Hundreds of women have been killed throughout Mexico in 2020, as well.75 Despite a growing distance from the creation of Fatal Migrations in 2016 and the 2004 posthumous publication of 2666, the large amounts of death caused by the border persists. While the feminicides have seemingly “spread” throughout Mexico, the causes are largely same and continue to go unacknowledged.76 Death is central throughout both works, emphasizing that bodies are material, ecological, and political. By focusing on the place of the body, Begley and Bolaño point to the complications of the region and assert the importance of recovering those lost as a consequence. The border between the United States and Mexico is a political, economic, and unnatural divide. Examining the lives and deaths of those in the borderlands calls attention to the inhumane processes of monitoring and maintaining the border. The realities of border violence persist while the silence that surrounds each death remains.

Notes

- Grupo Beta is an organization sponsored by the Mexican government aimed at the protection of human rights for migrants. They provide services including search and rescues, abuse documentation, legal services, and even assistance for migrants to return home. “Grupos Beta de Protección a Migrantes,” Gobierno de Mexico, https://www.gob.mx/inm/acciones-y-programas/grupos-beta-de-proteccion-a-migrantes, accessed September 13, 2020. Written as an introduction, Daniel Alarcón’s accompaniment to “Fatal Migrations” addresses the realities facing migrants along the border and explains Josh Begley’s digital piece. Daniel Alarcón and Josh Begley, “Fatal Migrations: Some of The Places People Died While Trying to Cross The Border,” The Intercept (blog), June 4, 2016, https://theintercept.com/2016/06/04/fatal-migrations/. ↩

- See Peter Andreas, Border Games: Policing the US-Mexico Divide, 2nd ed. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009). ↩

- Jason De León, The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015), 67. ↩

- Joseph Nevin’s book, Operation Gatekeeper: The Rise of the “Illegal Alien” and the Remaking of the US-Mexico Boundary, clearly outlines the history of fortifying the US-Mexico border beginning in El Paso, TX and moving to San Diego, CA. The escalation of border security accounted for the natural world with an explicit turn to weaponizing it in the mid-1990s. Joseph Nevins, Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond: The War On “Illegals” and the Remaking of the US–Mexico Boundary, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2010). Also see, Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith, Melissa McCormick, Daniel Martinez, and Inez Duarte, “The ‘Funnel Effect’ & Recovered Bodies of Unauthorized Migrants Processed by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, 1990-2005,” (Binational Migration Institute Report Submitted to the Pima County Board of Supervisors, October 2006), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3040107, which outlines how the rise in migrant deaths are the direct result of funneling them into dangerous environments. ↩

- De León, The Land of Open Graves, 4. ↩

- Sarah Jaquette Ray, The Ecological Other: Environmental Exclusion in American Culture, 2nd ed. (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2013), 1. ↩

- Warwick Anderson, “Excremental Colonialism: Public Health and the Poetics of Pollution,” Critical Inquiry 21, no. 3 (1995): 640–69. ↩

- Anderson, “Excremental Colonialism”, 643. ↩

- Juanita Sundberg and Bonnie Kaserman, “Cactus Carvings and Desert Defecations: Embodying Representations of Border Crossings in Protected Areas on the Mexico—US Border,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 25, no. 4 (August 1, 2007): 727–44, https://doi.org/10.1068/d75j. ↩

- Sundberg and Kaserman, “Cactus Carvings,” 738. ↩

- Ray, The Ecological Other, 6. ↩

- Ray, The Ecological Other, 1. ↩

- Christina Holmes, Ecological Borderlands: Body, Nature, and Spirit in Chicana Feminism, Reprint ed. (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2016), 30. ↩

- Ray, The Ecological Other, 140. ↩

- Sundberg and Kaserman, “Cactus Carvings,” 727–44. ↩

- Roxanne Lynn Doty, “Crossroads of Death,” in The Logics of Biopower and the War on Terror: Living, Dying, Surviving, ed. C. Masters and E. Dauphinee (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 3–24. ↩

- Ray, The Ecological Other, 154. ↩

- Luke Turf, “Illegal immigrants turn dessert into trash dump,” Tucson Citizen, August 17, 2003. ↩

- No More Deaths, “Footage of Border Patrol Vandalism of Humanitarian Aid, 2010-2017,” January 17, 2018, video, 1:29, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eqaslbj5Th8&feature=emb_title. ↩

- Sundberg and Kaserman, “Cactus Carvings,” 727–44. ↩

- Ray, The Ecological Other, 155. ↩

- Events like “The Migrant Trail” invite people (primarily American citizens) to hike from the border to Tucson, Arizona, actively encouraging participants to move through the desert landscape. Similarly John Annerio recreates migrant movement in his book Dead in their Tracks: Crossing America’s Desert Borderlands in the New Era (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2009). ↩

- In Francisco Cantú’s memoir The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border, he writes about the movement of border patrol agents through the border landscape without caution or regard for the environment. In one instance, after a high speed chase with drug smugglers Cantú and another agent come across an abandoned truck which they “drove . . . into a wash until it became stuck, and we slashed the unpopped tire, leaving it there with the lights on and the engine running.” Francisco Cantú, The Line Becomes a River (New York: Riverhead Books, 2018), 30. ↩

- Alarcón and Begley, “Fatal Migrations.” ↩

- Alarcón and Begley, “Fatal Migrations.” ↩

- Some estimates are as high as 8,000 people who have died since the mid-1990s until now. The numbers are hard to track as many migrants are never recovered and the amount of inconsistencies between organizations. See James Verini, “How US Policy Turned the Sonoran Desert into a Graveyard,” New York Times, August 18, 2020. ↩

- Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), viii. ↩

- Bennett, Vibrant Matter, 13. ↩

- Holmes, Ecological Borderlands, 10. ↩

- See Nevins, Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond; Andreas, Border Games; and De Leon, Land of Open Graves. ↩

- Jessica Auchter, “Border Monuments: Memory, Counter-Memory, and (b)Ordering Practices along the US-Mexico Border,” Review of International Studies 39, no. 2 (2013): 291–311. ↩

- Marcela Valdes, “Alone Among the Ghosts: Roberto Bolaño’s 2666,” Nation, November 2008. ↩

- Roberto Bolaño, 2666: A Novel, trans. Natasha Wimmer, reprint ed. (London; New York: Picador, 2009), 353. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 354. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 353–4. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 357. ↩

- See Melissa W. Wright, Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Capitalism (New York: Routledge, 2006). Elvia R. Arriola, “Accountability for Murder in the Maquiladoras: Linking Corporate Indifference to Gender Violence at the US-Mexico Border” in Making a Killing: Feminicide, Free Trade, and La Frontera (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010). Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World-System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century, 1st ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011). ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 359. ↩

- Wright, Disposable Women. ↩

- Sarah Hill, “Purity and Danger on the U.S-Mexico Border, 1991-1994,” South Atlantic Quarterly 105, no. 4 (October 1, 2006): 777–99, https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-2006-010, 778. ↩

- Hill, “Purity and Danger,” 789. ↩

- Hill, “Purity and Danger,” 779. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 372. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 372. ↩

- Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011), 5. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 391. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 391. ↩

- See De León, The Land of Open Graves. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 392. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 112. ↩

- Tom Lynch and Scott Slovic, Xerophilia: Ecocritical Explorations in Southwestern Literature, 1st ed. (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2008), 12. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 392. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 392. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 473. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 632. ↩

- Bolaño, 2666, 633. ↩

- Todd Miller, Empire of Borders: The Expansion of the US Border Around the World, 1st ed. (Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2019), 24. ↩

- Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion. 2 ed. (New York: Routledge, 2014), 44. ↩

- Hill, “Purity and Danger.” ↩

- Hill, “Purity and Danger.” ↩

- At present there are “53 towers equipped with cutting-edge surveillance technology: highly sophisticated cameras that could see seven miles away, even at night, sensing the heat generated by living creatures; ground-sweeping radar systems that also fed into command and control rooms where bleary-eyed agents stared into monitors” (Miller, Empire of Borders, 80). ↩

- Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (New York : Cambridge, MA: Zone Books, 2017), 21. ↩

- “‘Drug Dealers, criminals, rapists’: What Trump thinks of Mexicans,” BBC News, August 31, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-us-canada-37230916. ↩

- Missing Migrants Project, accessed September 14, 2020, https://missingmigrants.iom.int/. ↩

- Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty, 25. ↩

- Donald Trump (@realDonaldTrump), “The powerful Trump Wall is replacing porous, useless, and ineffective barriers in high traffic areas requested by Border Patrol. Illegal crossings are dropping as more and more Wall is completed! #BuildTheWall,” Twitter, January 11, 2020, https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/1216105951905882113?lang=en. ↩

- Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty, 42. ↩

- Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 2. ↩

- Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty, 122 ↩

- Matthew Choi, “Trump: Military will defend border from caravan ‘invasion,’” Politico, October 29, 2018. ↩

- Jens Manuel Krogstad, “Key Facts about Refugees to the US,” Pew Research Center, October 7, 2019, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/07/key-facts-about-refugees-to-the-u-s/. ↩

- According to Human Rights Watch, Remain in Mexico has affected approximately 56,000 asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border and resulted in the majority of applications for asylum being denied. “Q&A: Trump Administration’s ‘Remain in Mexico’ Program,” Human Rights Watch, January 9, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/01/29/qa-trump-administrations-remain-mexico-program. Also see Emily Green, Molly O’Toole, and Ira Glass “688: The Out Crowd,” November 15, 2019, in This American Life, produced by WBEZ, podcast, MP3 audio, https://www.thisamericanlife.org/688/the-out-crowd. ↩

- “Laws Waived for Border Wall Construction,” National Parks Conservation Association, May 30, 2019, https://www.npca.org/resources/3295-laws-waived-for-border-wall-construction. ↩

- Humane Borders, “Migrant Death Mapping,” interactive map, https://humaneborders.info/ ↩

- Natalie Gallón, “Women are being killed in Mexico at record rates, but the president says most emergency calls are ‘false,’” CNN, July 16, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/05/americas/mexico-femicide-coronavirus-lopez-obrador-intl/index.html. ↩

- Lorena Rios Trevino, “AMLO and the Feminicides”, Jacobin, May 10, 2020. ↩