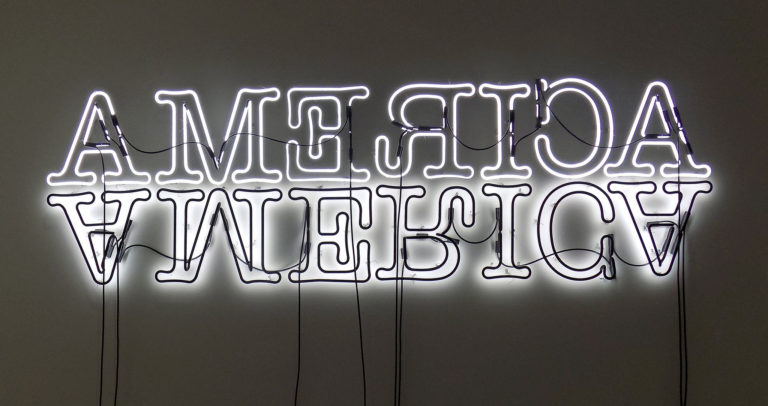

In this contribution, Chris Nickell and Adam Benkato think together about the mobilization of Blackness in Arabic hip hop from two different contexts: a rap battle in Beirut, Lebanon and music videos from Benghazi, Libya. In both, hip hop artists confront Blackness with the nation through the Afro-diasporic medium of hip hop. Although the examples we consider here participate, in several ways, in hip hop’s larger generic functions as a globalized Black medium of resistance, they also bolster pre-existing discourses of race and racism, anti-Blackness in particular. We argue that this seeming contradiction—instances of anti-Blackness appearing in an iteration of a Black expressive form—is in fact a feature, not a bug, of the flexible way the genre works. We have paired these two examples, which we describe and analyze individually given their differing social contexts as well as our differing research focuses, in order to glimpse the discursive level at which racecraft functions.

Keyword: masculinity

Review of Measuring Manhood: Race and the Science of Masculinity, 1830–1934 by Melissa N. Stein (University of Minnesota Press)

Melissa N. Stein’s Measuring Manhood tackles the complex intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and their attendant “sciences” across a century of US history. While the burgeoning fields of ethnology and sexology were equally prominent in Europe during this period, her focus on the US specifies the ways in which American “racial scientists” and sexologists differed from their European counterparts, as their research was often used to justify or bolster nation-specific cultural norms and legislation. The concept of masculinity was not simply a matter of “manhood” in the narrow sense, but carried with it a glut of other associations: humanity, civilization, citizenship, intelligence, morality, whiteness, cisgender heterosexuality, and middle-class restraint. Stein manages to convey the complexity and reciprocity of these constructions in each chapter with careful argumentation and ample examples.

Review of Football and Manliness: An Unauthorized Feminist Account of the NFL by Thomas P. Oates (University of Illinois Press)

In ‘Football and Manliness,’ Thomas B. Oates offers a prescient intersectional feminist analysis of the central symbolic place of the National Football League in U.S. culture and politics. In each chapter, Oates provides close readings of various popular media texts, which, despite remaining secondary to the spectacle of televised games, profoundly shape the ideological work the NFL performs in relation to dominant constructions of race, gender, sexuality, and class. These texts include fictionalized cinematic and televised melodramas depicting the internal dynamics of professional football teams; sports media coverage of the NFL draft; self-help books authored by noted NFL coaches; computer-based games, including fantasy league football and Madden NFL; and lastly, the investigative reportage that ignited the NFL concussion scandal. As Oates succinctly posits, “these texts produce a complex but ultimately coherent set of stories about gender, race, and contemporary capitalism” (20).

Review of Atari Age: The Emergence of Video Games in America by Michael Z. Newman (MIT Press)

Newman examines the early period of video games in America when arcades and game rooms emerged in suburban malls around the country, televisions became ‘entertainment centers,’ and computers and game consoles were one in the same. As an introduction to the politics and economics of early home video games, Atari Age is a good starting point for readers looking to familiarize themselves with the foundational actors and social contexts surrounding the industry in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Every Little Thing He Does: Entrepreneurship and Appropriation in the Magic Mike Series

This essay analyses the theatricalized performance of stripping in the popular films Magic Mike (2013; dir. Steven Soderbergh) and its sequel, Magic Mike XXL (2015; dir. Gregory Jacobs). Following a critical dance studies approach that attends to the intersection of body and gesture with socio-political, historical, and economic structures, I suggest theatricalized sexual labour in these films reveals the racial exclusions from the ideology of entrepreneurship. Considering the appropriation of black aesthetics in Magic Mike XXL’s performances of striptease, the film seeks to evaporate the spectre of race, that is, the way the white fantasy of the entrepreneurial subject is supported by the appropriation of racialized and especially black labour.

Don Loves Roger

Elisa Kreisinger’s clever reworking of the dialogue from “Mad Men” introduces to the show’s portrayal of 1950s corporate and advertising culture a queer noise that makes audible the homoerotic desires and potentialities that are always already embedded in these spaces. Sound and silence are crucial to this intervention, for the desires that are otherwise unspeakable in this space are articulated in and through silences. By making silences not only speak, but speak queerly, Kreisinger inverts the pattern of silencing that has historically been used to render queer desires publicly unspeakable.