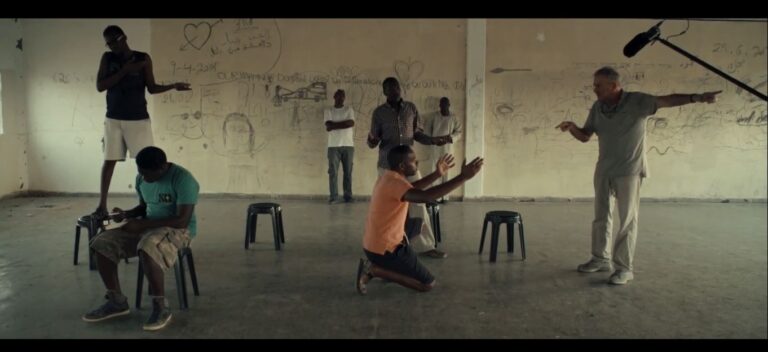

The recent arrival in Israel of thousands of refugees from countries like Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Sudan has triggered a spate of hate crimes and mob violence. Asked about these asylum seekers in 2012, Likud-party member Miri Regev called them a “cancer.” For this comment, she later apologized—not to the African asylum-seekers but to Israeli cancer survivors, and she expressed regret for comparing them to Africans. Around that same time, Interior Minister Eli Yishai of the Shas Party told a reporter that “this country belongs to us, to the white man.” Continuing on, he stated that he would use “all the tools [necessary] to expel the foreigners, until not one infiltrator remains.” While the racial dynamics of Israel have been thoroughly examined with respect to both intra-Jewish tensions (Ashkenazi supremacy) and the Palestinian issue (white settler-colonialism), in this essay, I want to theorize Israeli whiteness with respect to the African refugees. Specifically, I will examine two recent Israeli documentaries dealing with African refugees—Hotline (dir. Silvina Landsmann, 2015) and Between Fences (dir. Avi Mograbi, 2016). Both openly demonstrate solidarity with the African asylum-seekers, but they do so in different ways, and if the former film leaves the racial hierarchies of Zionism intact, the latter works to shatter them.

Keyword: whiteness

What is Whiteness in North Africa?

This entry sketches a matrix for conceptualizing race in/ and North Africa that takes Arabness, indigeneity, Islam, the Sahara, and slavery as orienting keywords. It suggests an approach to a geopolitically-grounded whiteness as social currency and aspiration that is both based in specific regional economic history and also reaches outward toward globally-circulating formations of racial hierarchy. Acknowledging the distinct legal, colonial, and state histories under and through which racialization has proceeded in North and Saharan Africa since the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, this entry aims to draw out the ethical imaginaries through which bodies have been marked and categorized in this region. These ethical imaginaries have operated through their attendant languages, memories, and performances to enable racisms and colorisms with violent and enduring material consequences. Under the headings “Racialized Enslavement,” “Whiteness and Arabness,” “Race and the Sahara,” and “Race in North African Popular Culture,” I offer brief introductions to these discursive formations, histories, and conceptual intersections and offer suggested readings for each.

Review of Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai`i and Oceania by Maile Arvin (Duke University Press)

Arvin explains how dispossessing Polynesians was predicated on a logic of settler colonialism inflected by white supremacy. Casting Polynesians as white—specifically, as “almost white”—as opposed to distancing Polynesians from Caucasians, simultaneously provided white settlers the justification they needed to occupy large swaths of Oceania and precluded Polynesians from enjoying the full set of rights available to non-almost whites. By establishing a clear racial continuity between settlers and Polynesians, possession through whiteness made whiteness indigenous to the islands; doing so “suited [settlers’] own claims of belonging to Polynesia while [also soothing] colonizers’ racial anxieties about those they dispossessed.” Throughout the book, Arvin argues that anti-Blackness was as pronounced and as integral in possessing Polynesians as whiteness and calls for future research that more centrally examines the specific and nuanced functions of whiteness, Blackness, and Indigeneity in Melanesian and Micronesian contexts.

Review of Talking White Trash: Mediated Representations and Lived Experiences of White-Working Class People by Tasha R. Dunn (Routledge)

In Talking White Trash, Tasha R. Dunn provides a multi-methodological investigation into the representations of white working-class people on screen and the everyday lives of members of the white working-class. Her work provides a nuanced way to understand the reinforcement of stereotypical depictions of this population, as well as how the white working class “talks back” to these representations. The book draws from the current political and cultural moment to assert how white working-class identity is constructed, and advocates for a more complex reading of this population than is often provided in mediated texts.

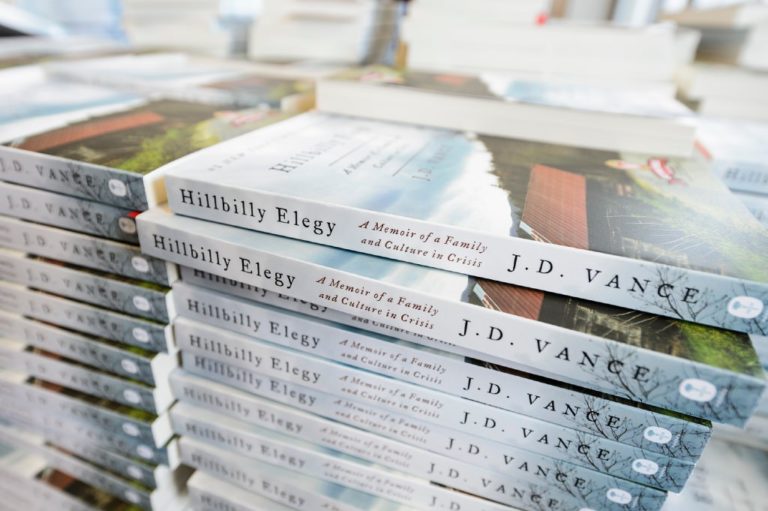

Not About White Workers: The Perils of Popular Ethnographic Narrative in the Time of Trump

This essay rasies three concerns about popular contemporary ethnographies that focus on the rural and white “working class.” First, these ethnographies are not treated as partial accounts of cultural experience but are instead taken as straightforward political and economic analyses. Second, these ethnographies amplify an “empathy mandate,” which demands that our political actions center on trying to understand misunderstood populations—in this case, the so-called “white working class.” Third, by disarticulating the cultural markers of “working classness” from the material conditions of class, these ethnographies obscure the political significance of “working class.” Ethnographies of “white working class” experience may be useful only if we treat them as small openings that lead to bigger and broader stories, rather than as complete and transparent explanations of what is going on.