برای ترجمهی این مقاله به زبان فارسی به این لینک مراجع فرمایید

For a Persian translation of this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.25158/L10.1.12.fa

Every spring equinox, Iranians celebrate Nowruz1 with a popular jingle:

My Master, hold your head up high,

My Master, why don’t you laugh?

It’s Nowruz, it’s one day a year!

A man dressed as “Haji Firuz” sings this seemingly innocuous rhyme. His costume requires only a red outfit, a tambourine, and, most notably, a blackened face.

***

In 2012, I gave a talk on race in Iran, where I described Haji Firuz’s roots in Iran’s history of slavery. The audience, a mix of academics and community members from the greater Tehrangeles area, met my presentation with a mix of applause and booing. One individual stood up and said, “everything you’ve said is wrong. I’ll bring you a source that proves where Haji Firuz is really from.”2 The next day, he handed me a handwritten polemic, “Who is Haji Firuz, and where did he come from?”3 The essay described him as an age-old character of happiness and good cheer, whose blackened face has origins in a Zoroastrian past.4

Haji Firuz does have a long history, but not quite as long as some may think. His supporters insist on his ancient origins, excusing his blackened face with a myriad of myths. But records of a Nowruz herald named Haji Firuz are less than a century old, mostly from after the abolition of slavery in 1929.5 This article examines the popular genealogies surrounding Haji Firuz and how they obfuscate the role of racism in creating this holiday figure.

***

Blackness serves as a specific marker in the history of slavery and race in Iran. Over the centuries, the term siyah has expanded or contracted to include different groups of peoples. During the Safavid era, siyah was more likely to refer to South Asians, particularly enslaved eunuchs.6 By the late nineteenth century, siyah referred to East Africans enslaved by well-to-do and royal Iranians. While other populations had before been subject to enslavement, including Caucasians, Central Asians, and South Asians, geopolitical changes left East Africans most vulnerable, thus racializing Iran’s system of slavery to the point where almost anyone referred to as siyah, “Black,” was likely enslaved.

Treaties promising to end the Persian Gulf slave trade were repeatedly made and broken until 1929, when Reza Shah’s cabinet pushed the abolition of slavery in a bid to appear modern and Westernized on an international stage. As such, any references to the enslavement of peoples were erased from public spaces. Freedpeoples, overwhelmingly of African ancestry, were also erased as the Shah openly embraced the Aryan myth,7 which purported that Iranians were inheritors of an ancient white racial legacy.8 The major exception to these elisions, however, came in siyah-bazi, the blackface minstrelsy shows that mocked enslaved people. As the collective memory waned and the idea of Iranian slavery became taboo, these shows grew in popularity, and alternate explanations emerged to justify and preserve them.

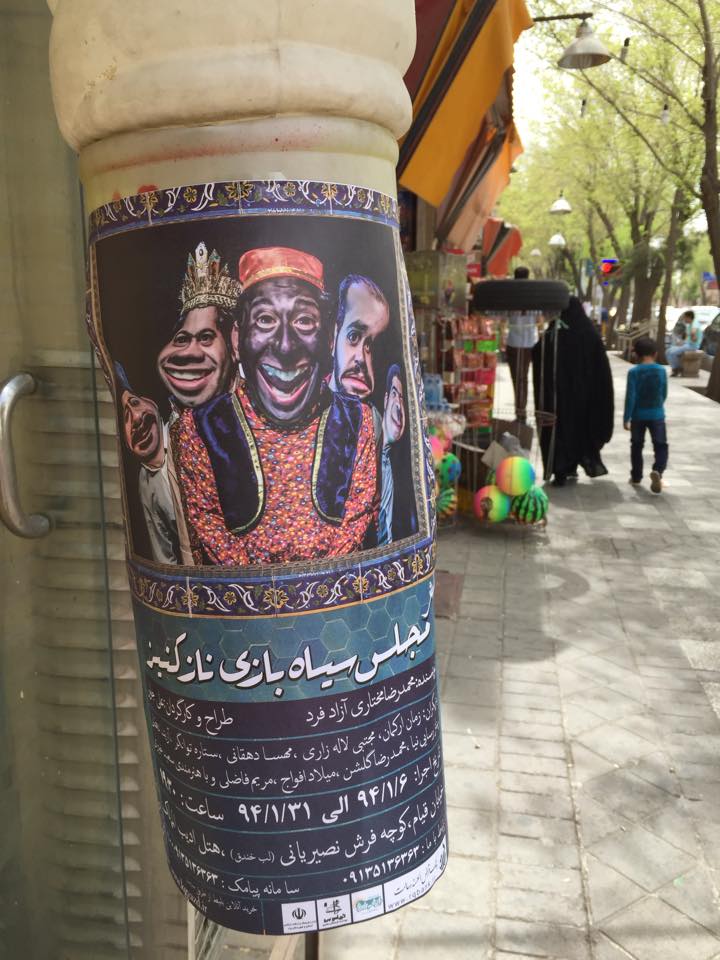

Siyah-bazi, “playing black,” performances developed at the Qajar court in the late nineteenth century. Again the term siyah morphed, now referring to a character who appears onstage in blackface. These performances are usually set at court or in high society and are performed year-round, making broader social critiques relevant to the audience’s everyday lives.9 Similar to blackface minstrelsy in the United States, these shows rely on slapstick and other forms of comedy through music, song, dance, as well as jokes based on miscommunication or misunderstandings, and more. During the Pahlavi era, siyah-bazi went from a court show performed for royals to one seen in the streets and theaters of major urban centers across Iran.

The legacy of slavery in siyah-bazi is, however, highly specific. While elite and wealthy Iranians had enslaved men, women, and eunuchs, siyah-bazi targeted caricatures of eunuchs. Eunuchs served as harem guards, as confidants, and were trusted managers of day-to-day operations at courts. High-ranking eunuchs held more power than many of the free members of court.10 Their hyper-sexualization and desexualization—as men who required castration so they could interact with court women freely without suspicion—is a central theme in siyah-bazi. Even the names of the siyah characters, often Mubarak or Haji Firuz, are derived from popular names for slaves in Iran and the Persian Gulf region.11

Yet the rendering of the main subject of siyah-bazi—a simpleton prone to mistakes—in the image of the eunuch reminds the audience that no matter what power a eunuch may have had, he was still enslaved and vulnerable to denigration as an enslaved person. The siyah in siyah-bazi speaks in a high-pitched voice, has accented Persian, is in close quarters with their master, manages their master’s work, and so forth. He is often lustful, but not a suitable partner.12 In sum, the siyah draws directly from crude stereotypes about eunuchs in the Qajar era.

Haji Firuz emerged out of siyah-bazi, and his popularity is tied to the growth of these performances in the 1920s and 1930s in Tehran.13 While siyah-bazi remained broad in their scope, Haji Firuz was associated with the new year.14 His striking appearance and jingles made him a recognizable fixture in Nowruz celebrations. As the Pahlavi shahs presented themselves as inheritors of an ancient Iran, Iranian nationalists sought to locate examples of “folk” theater not tied to Islam as evidence of the depth of popular culture.15 Siyah-bazi became recognized as a genre of theater unto itself, and actors, such as Sa’di Afshar, built their entire careers around the character of the siyah and achieved national fame.16

The popular cause to defend Haji Firuz came to a fore after the 1979 revolution. While some of the narratives developed during the Pahlavi era, they became more formalized and virulent out of a reaction to the Islamic Republic and its control over public culture in Iran. Ayatollah Khomeini was known for indicting the United States as the very embodiment of injustice, including racism,17 and the Islamic Republic fashioned itself as the leader of anti-imperialist movements for the Global South. But siyah-bazi jeopardized the Islamic Republic’s reputation as an anti-racist international force, as non-Iranians would readily recognize it as blackface. To mitigate this, government officials cracked down on siyah-bazi in the early years of the Islamic Republic. Some siyah-bazi theater actors continued with their shows but avoided painting their faces. Haji Firuzes were generally discouraged and sometimes arrested. Because the Islamic Republic had also banned particular forms of music and dancing in public on religious grounds, many viewed the new policies as “anti-happiness” and were unable to extricate the racial reasons why banning Haji Firuz might be different than the justifications for regulating music.18 Because of his association with Nowruz, a pre-Islamic holiday, the defense of Haji Firuz became especially important to those who felt antagonized by the Islamic Republic.

As these political changes threatened Haji Firuz’s existence, those defending him developed complex explanations. Some attributed his blackface to soot from the Chaharshanbe Suri fires that Iranians jump over on the last Tuesday night of the year, while others suggested that Haji Firuz was actually a Zoroastrian priest whose face was blackened from tending to a sacred fire. And yet, I have never come across an account of anyone becoming black in the face from jumping over a fire, nor does the idea that Haji Firuz might have been a mobad fit with Zoroastrian ideas of purity and cleanliness. In both cases, the explanations take examples that are popularly considered as native or ancient to Iran and make logical leaps to connect them to Haji Firuz as a part of a shared cultural heritage.

Still more complex explanations evolved as well, where some described him as a reincarnation of Siavash, a character in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. The Shahnameh, a tenth-century epic, gained importance amongst nationalists in the twentieth century who viewed it as a preservation of a pure pre-Islamic “Persian” past and culture. The Shahnameh presents Siavash as a chivalrous and dignified prince. His name, Sia-vash, originally Sia-vakhsh, refers to his black horse.19 Over time, the reading of Siavakhsh became rare, allowing defenders of Haji Firuz in the twentieth century to interpret it as “black in appearance” to fit their explanations. This does not align with premodern etymologies of the name, and no reference in the Shahnameh suggests that he was Black or a jester.20 Yet in 1983, Mehrdad Bahar linked Haji Firuz to Siavash, Mesopotamian deities, and rites in the afterlife. Bahar described Haji Firuz as Siavash arisen from the dead, his blackened face an ashy return to the living world.21 Bahar’s treatment ignored any of the direct links between Haji Firuz’s persona and the caricatures of African slaves at the Qajar court. Nor does it mention why a resurrected prince would use pidgin Persian or expressions of servitude, such as calling for his master. Instead, Bahar echoed narratives that had emerged in the Pahlavi era, erasing any references to slavery or race, and created an explanation that justifies Haji Firuz’s presence in Nowruz festivities and renders his person into a cultural cause that must be preserved for the sake of history. Connecting Haji Firuz to elements of pre-Islamic Iran, either through distorted ideas of Zoroastrianism or misreadings of characters from the Shahnameh, frames Haji Firuz as a cultural figure whose existence is threatened by a hardline Islamic government.

At the same time, material representations of Haji Firuz grew more common, further embedding his visuality into Nowruz traditions. From Haji Firuz yarn dolls made by blind patients to raise money for the Kahrizak Foundation to greeting cards of Haji Firuz playing his tambourine, Haji Firuz has been consistently portrayed with a red outfit, a rounded hat, and a blackened face.22 All material renderings rely on a blackened face to visually indicate that this object is a Haji Firuz. A doll or an illustration without a black face may not even be recognizable as a Haji Firuz, but rather may be mistaken for a doll wearing any red outfit. The importance of the blackened face, however, is diminished in live-action, as other characteristics, such as accent or comportment can communicate the racialized caricature in the absence of blackface.

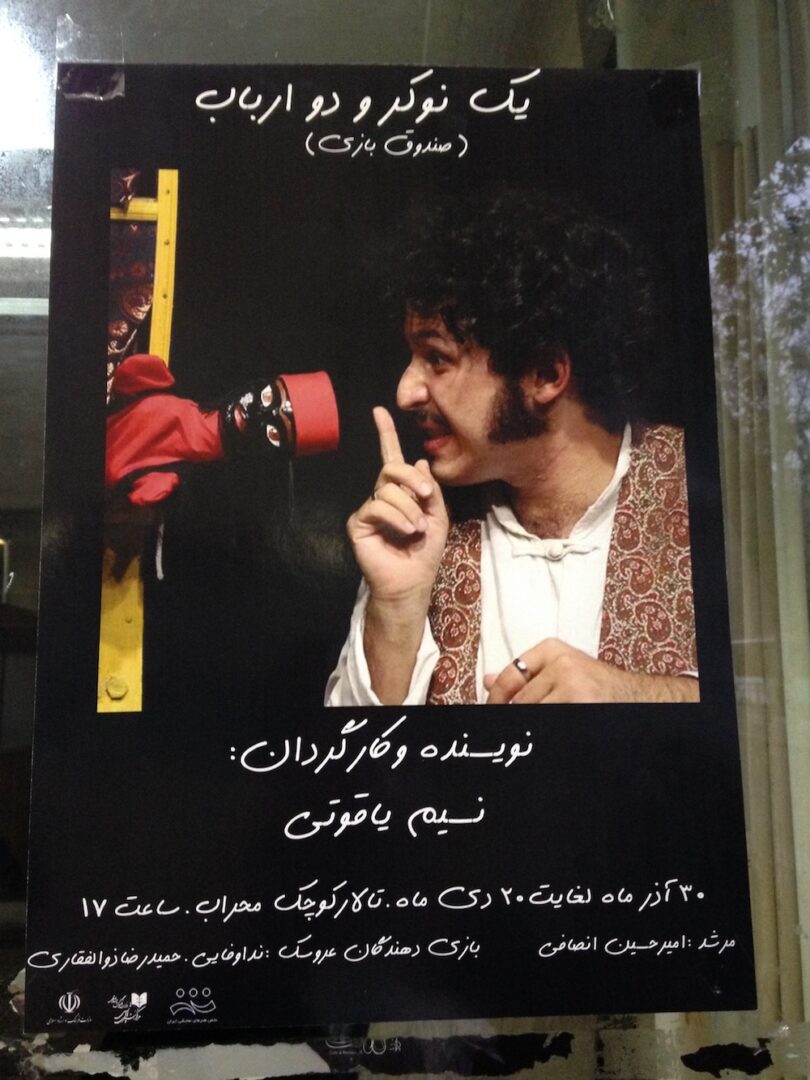

I met with Javad Ensafi, a siyah-bazi actor at Mehrab Theater in Tehran, in 2015. Ensafi, who has performed on the radio, in television, in films, and on stage since the 1970s, spoke with me about his experiences in theater before going onstage as the siyah in Chillih Zari va Chillih Amu Jun. Ensafi ushered me into a dressing room to talk about siyah-bazi, its history, and his experiences.23 His wife, Forugh Yazdan-Ashuri, who also performed in the night’s show, joined the conversation as well.

Ensafi opened the discussion with the genre’s ancient roots, which he dated to the pre-Islamic period per rock reliefs that depicted court life. “There’s always a jester,” he said, “and that is where the siyah comes from.” But the reliefs are not colored, so I pushed him on where the blackface comes from. Ensafi described the blackface as a marginal detail, a visual device that highlights the funniest character onstage. He made this same argument about Haji Firuz as well: “Haji Firuz does not need to appear in a blackened face.” In fact, in recent years, Ensafi has appeared on television in the role of Haji Firuz, dressed in a red outfit without a blackened face. Ensafi’s own book on Nowruz traditions, however, includes the following description:

In some cities, among them Tehran, around the time of Nowruz two individuals—one Black (Haji Firuz) and one an older man (Amu Nowruz)—arrive and sing, and with their stylized sentences perform a type of show that brings people’s happiness and laughter.24

Although Ensafi suggested that Haji Firuz does not need a blackened face, his own writing highlights that Blackness is the defining element of his character.

Ensafi’s description of Haji Firuz as not requiring a blackened face can be understood as a semantic effort to preserve the character in face of government hostility.25 Ensafi, who has acted as a siyah for the past few decades, recalled various government officials from different departments approaching him and requesting—or perhaps strongly suggesting—that he not blacken his face for his performances during the early period of the Islamic Republic. Similarly, he abandoned blackening his face in state television roles.26 His role as the siyah remained relatively unchanged. “I say, ‘you don’t want me to have a blackened face? Fine. But it changes nothing about the rest of the show.’”27 Indeed, blackface minstrelsy requires more than simply blackening one’s face. In that night’s performance, Ensafi began with a bare face, maintaining the other elements that distinguished his character—his simple red outfit, his pidgin Persian, and his body’s comportment. About halfway through the program, he theatrically applied a black ointment to his skin, to the cheers of the audience.28 Though his acting remained unchanged, the audience appreciated the second half of the show much more, as evidenced by their louder cheers, more boisterous laughs, and their palpable excitement.

Ensafi’s involvement in siyah-bazi remains a passion project for him and his wife, as well as their son, Amir Husayn Ensafi, who also acts onstage. Before I wrapped up my conversation with Ensafi, Yazdan-Ashuri pulled me aside, asking why I was interested. I told her I was writing about siyah-bazi and its parallels with US blackface minstrelsy. “Oh good,” she replied, “you can tell everyone how different ours is from that. Everyone keeps saying this is racist, but we say no, this is tradition.”29

Other lovers of siyah-bazi and Haji Firuz do not view the government’s stance as one motivated by anti-racist inclinations. Instead, they see the Islamic Republic as choking the nation of folk entertainment. Though dressing up as a Haji Firuz is not technically illegal in Iran, officials do sometimes arrest Haji Firuzes per public indecency laws, especially if they are performing—dancing, singing, and the like—in public spaces. As such, these arrests are sporadic and not uniform. They are, however, often publicized by supporters of Haji Firuz on the internet, where the arrests are described as an unjust encounter between a simple, happy tradition versus an authoritarian government. For example, Iran Global, an online media outlet, published an image of an officer arresting a Haji Firuz with the following caption: “According to reports from Rasht, a Haji Firuz brought happiness and laughter . . . but officials of the oppressive regime attacked and arrested him.”30 The article’s caption casts this Haji Firuz as innocent, only wanting to make others happy, an intention crushed by the overpowering presence of the Islamic Republic.

This remained a common stance until recently when Iranian rapper Hichkas (Soroush Lashkari) released the song “Firooz” in 2015.

Instead of casting the issue of Haji Firuz as a cultural war with the Islamic Republic, Lashkari pointed to the economic conditions that drive people to dress as Haji Firuzes and the underlying history of slavery informing the character’s behavior. While some formal Nowruz performances do include Haji Firuz, most Haji Firuzes are typically younger men from lower socio-economic backgrounds who busk in between cars stuck at traffic lights or out on sidewalks to make some extra money in the holiday season. Lashkari’s lyrics describe a young man, the family breadwinner, who has spoken to his boss about his financial situation to no avail, who cannot pay the bills, who has hit a dead end in every effort and has no option but to lose his dignity acting as a Haji Firuz on the streets.

Lashkari continues in sharp irony, “dance, dance, dance / let’s celebrate slavery” and, “I suppose every day in Africa is Nowruz / Because if this is how we calculate it, it must be full of Haji Firuzes.” He then launches into a series of questions, including the pointed “where did our ancestors buy you from?” Lashkari’s rap reflects two elements in the existence of Haji Firuz in Iran—first, that Haji Firuzes make a mockery of Africans who were forcefully brought to Iran, and second, the practice persists primarily in Iran because of economic conditions that leave low-wage workers little recourse. Lashkari’s sentiments echo those of Mahdi Akhavan-Sales, who, in 1951, wrote a footnote to a Nowruz poem in which he described his hatred of the Haji Firuz practice that has emerged out of Tehran for its ridiculing of slaves. Akhavan-Sales clarified that his animosity was not towards the people who are driven to do it out of hunger, but rather for the tradition as a whole.31 While Akhavan-Sales buried his complaints in the notes of his anthology, Lashkari’s rang out on his global platform, sparking discussions on social media platforms almost immediately.32 Fans questioned whether Haji Firuz was linked to slavery, if Haji Firuz could still be Haji Firuz without a blackened face, and what should be done about the tradition as a whole.

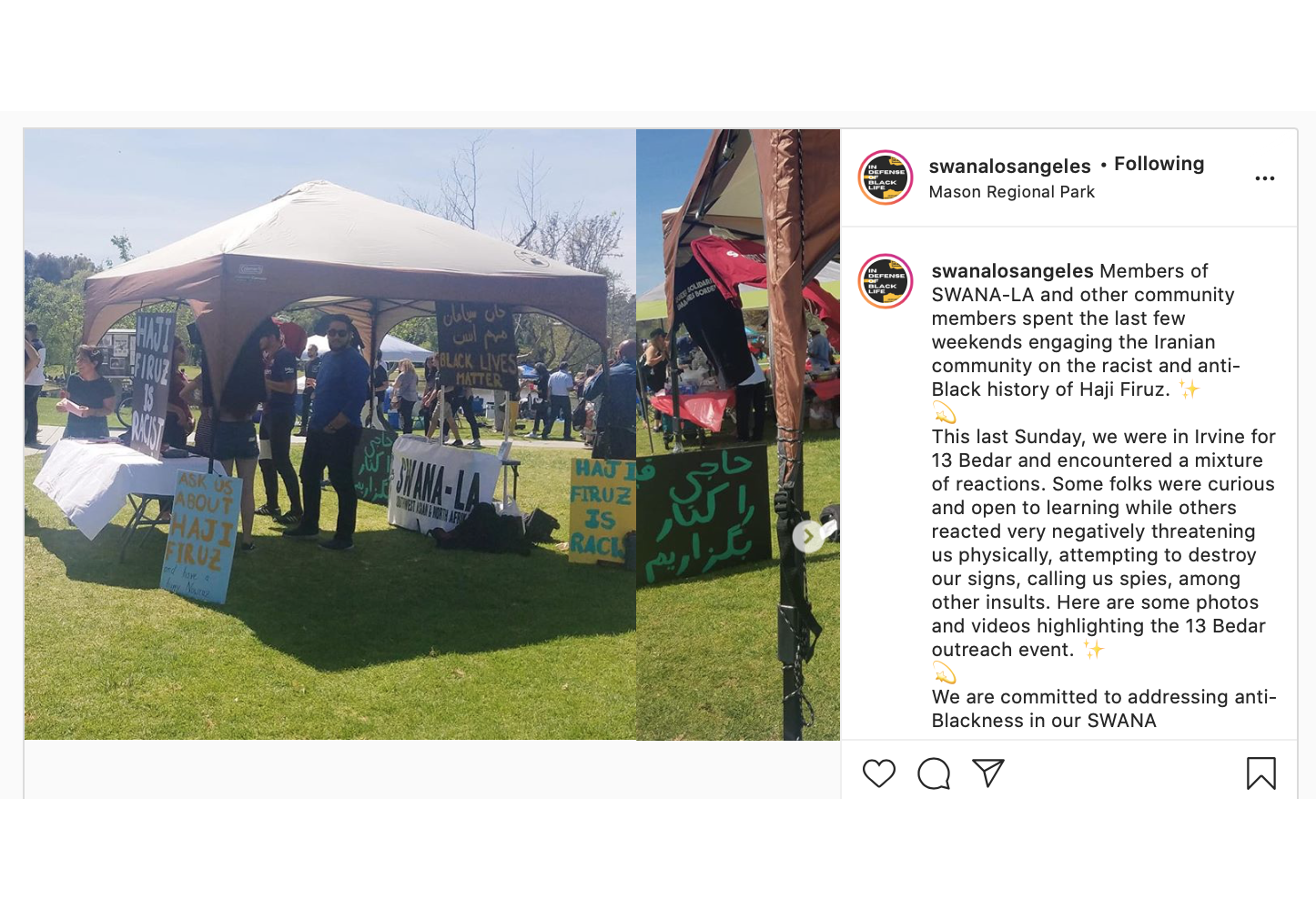

The question “who is Haji Firuz and where did he come from?” leads us down a myriad of complicated explanations, many obscuring or ignoring the history of slavery altogether, all in an effort to absolve oneself from enjoying the performance of a blackface minstrel. Perhaps we should rewrite the question and ask, “who is Haji Firuz, and how do we let him go?” In Nowruz of 2019, a local activist organization called SWANA-LA set up a booth at the annual Sizdah-bidar Nowruz picnic. Stationed at Irvine’s Mason Park, one of the largest Nowruz hubs drawing thousands of celebratory diaspora Iranians in Southern California, SWANA-LA members put up signs in Persian and English reading “Haji Firuz is Racist” and “We must put Haji Firuz aside.” While some attendees were receptive to their message, others threatened the activists, tore down their posters, and insulted them. In one exchange, an older man cried, “why are you doing this? I love Haji Firuz, he made me so happy, he made us all so happy.”33 His happiness, they replied, should not be predicated on defending a racist caricature, a feat that seems harder for some than it should.

Notes

- Nowruz, “new day,” coincides with the spring equinox and marks the first day of the new year. ↩

- Beeta Baghoolizadeh, “Iranian Racism: Its History and Its Lingering Legacy,” International Conference on the Iranian Diaspora, International Alliances Across Borders, UCLA, 2012. ↩

- “Haji Firuz kist, va az kuja amad?” ↩

- This reference to a Zoroastrian past is one deeply embedded in Iranian nationalism. Zoroastrianism was an imperial religion prior to Islam and continues to be practiced by a religious minority in Iran and around the world. During the Pahlavi era, Zoroastrianism grew significant to Pahlavi expressions of nationalism, and continues to be popular amongst nationalists. Afshin Marashi, Exile and the Nation: The Parsi Community of India and the Making of Modern Iran (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2020). ↩

- Haji Firuz’s static existence—the blackface, the red outfit, the tambourine and the jingle—is inseparable from nineteenth- and early twentieth-century iterations of slavery and racism in Iran. Beeta Baghoolizadeh, “Seeing Race and Erasing Slavery: Media and the Construction of Blackness in Iran, 1840–1960” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2018), 199–204. Angelita Reyes has written a comparative study of Haji Firuz, the Mammy, and Zwarte Piet. Angelita D. Reyes, “Perfomativity and representation in transnational blackface: Mammy (USA), Zwarte Piet (Netherlands), and Haji Firuz (Iran),” Atlantic Studies 16, no. 4 (2019): 521–550. ↩

- South Asians made up the majority of eunuchs who were “black” at the Safavid court (1501–1736), as opposed to Caucasian eunuchs who were “white.” Sussan Babaie, Kathryn Babayan, Ina Baghdiantz-McCabe, and Massumeh Farhad, Slaves of the Shah: New Elites of Safavid Iran (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2004), 158. Prior to the Safavid era, poets writing in Persian would use siyah to refer to East Africans or South Asians, depending on the associated words or context. Poets would pair siyah with hindu to refer to South Asians or with zangi to refer to East Africans. See Haft Peykar by Nizami (twelfth–thirteenth century), the Masnavi by Rumi (thirteenth century), Ganjoor, accessed August 15, 2020, https://ganjoor.net/nezami/5ganj/7peykar/sh5. ↩

- Baghoolizadeh, “Seeing Race and Erasing Slavery,” 164–206. The transition from a diverse range of enslaved peoples to almost exclusively East Africans paired with the rise of Aryanism amongst Iranian nationalists beginning in the late nineteenth century created a black-white binary. Prior to the late nineteenth century, Iranians viewed themselves as neither white nor black. ↩

- For a discussion on the ideologies surrounding the Aryan myth in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, see Reza Zia Ebrahimi, The Emergence of Iranian Nationalism: Race and the Politics of Dislocation (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016). ↩

- For a brief discussion of siyah-bazi theater, see Maziar Shirazi, “A Review of Tarabnameh, or, Why Are Iranian-Americans Laughing at Blackface in 2016?” Ajam Media Collective, December 7, 2016, https://ajammc.com/2016/12/07/why-are-iranian-americans-laughing-at-blackface-in-2016. ↩

- This was true for both eunuchs of East African or Caucasian backgrounds. For examples from the Qajar court, see ‘Azod al-Dowleh, Life at the Court of the Early Qajar Shahs, trans. Eskandari-Qajar (Washington: Mage Publishers, 2014), 49; Dust ‘Ali Khan Muayyir al-Mamalik, Khatirat-i Nasir al-Din Shah (Tehran: Naqsh-i Jahan), 18; I’timad al-Saltanih, Ruznamih Khatirat-i I’timad al-Saltanih (Tehran: Amir Kabir, 2010), 526–527. ↩

- A eunuch named Haji Firuz served as a eunuch at the court of Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848–1896). Baghoolizadeh, “Seeing Race and Erasing Slavery,” 84. Searches for “Firuz/Firooz” or “Mobarak/Mubarak” in the British Library materials in the Qatar Digital Library reveal the commonality of the names for enslaved men across the Persian Gulf region in the nineteenth century, including Iran. For example, see Files 5/191 III Individual Slavery Cases; File A/2 II Slave Trade, Correspondence with Bushire regarding slaves and their manumission certificates and applications, Qatar Digital Library, accessed August 1, 2020, qdl.qa. ↩

- For a photographic history of how eunuch’s portraits inspired clowns and minstrels in their shows between 1896 and 1906, see Baghoolizadeh, “Seeing Race and Erasing Slavery,” 67–114. ↩

- Sa’di Afshar, as narrated to Laleh Alam, ‘Ali Jināb Sīyāh: Zindigī va Khātirāt-i Sa’di Afshar (Tehran: Pūyandih, 2012), 47–48. ↩

- Haji Firuz dolls signal that by the 1960s and 1970s the character had expanded beyond simple street performances. “Poupée de chiffon, tunique de soie artificielle,” Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, 1979, accessed February 4, 2019, http://www.quaibranly.fr/fr/explorer-les-collections/base/Work/action/show/notice/799998-poupee-de-chiffon-tunique-de-soie-artificielle/page/1; “Poupée représentant un danseur,” Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, 1960s, accessed February 4, 2019, http://www.quaibranly.fr/fr/explorer-les-collections/base/Work/action/show/notice/73391-poupee-representant-un-danseur/page/1. Many thanks to Mira Xenia Schwerda for alerting me to these dolls. ↩

- Ta’ziyeh plays and Ashura processions are older forms of theater in Iran, however, because of their religious significance, they were not inscribed in the national canon in the way that siyah-bazi or Haji Firuz were. See Kamran Aghaie, The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi’i Symbols and Rituals in Modern Iran (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015) and The Women of Karbala: Ritual Performance and Symbolic Discourses in Modern Shi’i Islam (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005); William O. Beeman, Iranian Performance Traditions (Costa Mesa: Mazda, 2011); Kelsey Rice, “Emissaries of Enlightenment: Azeri Theater Troupes in Iran and Central Asia, 1906–44,” Iranian Studies (2020). ↩

- Afshar, ‘Ali Jināb Sīyāh: Zindigī va Khātirāt-i Sa’di Afshar. ↩

- Khomeini was exiled in November 1964 and returned to Iran in January 1979. From Najaf and Paris, he gave speeches where he linked the Shah’s rule to the United States until he returned for the revolution. Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 445, 461. ↩

- Negative feelings about these policies went beyond the regulation of Haji Firuz. Nahid Siamdoust discusses the changes in the broad scope of music regulation after the 1979 revolution. Nahid Siamdoust, Soundtrack of the Revolution: The Politics of Music in Iran (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2017). ↩

- The original form of Siavash, “Siiāuuaršan,” is derived from the Avestan for “the one with the black stallions.” “KAYĀNIĀN vi. Siiāuuaršan, Siyāwaxš, Siāvaš,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, accessed April 15, 2020, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kayanian-vi. ↩

- See Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh, Abu’ Qasem Ferdowsi: The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings) (New York: SUNY Press, 2007). ↩

- Mahmoud Omidsalar, “ḤĀJI FIRUZ,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI/5, 551–552, accessed December 30, 2012, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/haji-firuz. ↩

- Collection of the author, from 1995–2015. ↩

- Many thanks to Ali Karjoo-Ravary for joining me. ↩

- Javad Ensafi, Navid-i Bahar: Namayish-i siyah-bazi-yih Nowruz va Piruz (Tehran: Chap-i Mahrang, 1392), 33. Translation by author. ↩

- One may note that the material reliance on blackface, as is the case with dolls or illustrations, is not as necessary with human performances. Instead, the individual’s acting can cue the audience that he is a siyah and not just any person in a red costume. ↩

- Although Ensafi has had greater freedom recently in using blackface onstage, state television programs generally avoid it. ↩

- Conversation with Javad Ensafi, Mehrab Theater, Tehran, December 30, 2015. ↩

- “Chillih Zari va Amu Chillih Jun (Shab-i Yalda),” Mehrab Theater, Tehran, December 30, 2015. ↩

- Conversation with Forugh Yazdan-Ashuri, Mehrab Theater, Tehran, December 30, 2015. ↩

- “The Arrest of One Haji Firuz in Rashti + Photographs,” Iran Global, March 13, 2013, https://iranglobal.info/node/17066. ↩

- Mahdi Akhavan-Salis, Arghanūn: Majmu’ih Sh’ir (Tehran: Murvārīd, 1951), 77. Baghoolizadeh, “Seeing Race and Erasing Slavery,” 203. ↩

- @HichkasOfficial, Twitter, March 16, 2015, https://twitter.com/HichkasOfficial/status/578312152429293569. ↩

- Conversations with SWANA-LA member Pouneh Behin, April 1, 2019. @swanalosangeles, “Members of SWANA-LA and other community members…” Instagram, April 3, 2019, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bv0PPjpBLG2/?igshid=1i678q792tqrz. ↩