The review focuses on the practical work of Poor Queer Studies. Rather than retheorize queer studies from the class perspective of “rich” and “poor,” Brim makes a case study of his work as a professor of queer studies at the College of Staten Island (CSI). Insisting on the particularity of his and his students’ relationship to queer studies, Brim makes an example of the work they do together in the classroom, and the ways they live their studies on public transit, at home with their families, and in their part-time jobs. This review questions the extent to which poor queer studies differs from the modern university’s reduction of all education to career-training. Brim’s praxis of poor queer studies is always undertaken with individual students in specific socio-economic circumstances—a particularity that makes it different than market-driven job-training. This review also raises questions about the general applicability of this case study. Would poor queer studies work elsewhere as it does at CSI? Berlant’s idea of exemplarity is helpful in answering this question. Unlike examples that confirm a norm, there are examples that change norms. Brim’s example of poor queer studies works to exemplarily change what counts as normal. Practically, this means no longer thinking of queer studies as operating without class distinction—and reclaiming part of the work of the discipline from seemingly classless rich queer studies at places like Yale and New York University.

Keyword: university

Review of The University and Social Justice: Struggles across the Globe edited by Aziz Choudry and Salim Vally (Pluto Press / Between the Lines)

In this edited collection, Aziz Choudry and Salim Vally present reflections and analyses from scholar-activists in education studies, anthropology, literature, and cultural studies describing university-based and affiliated social movements. Through thirteen essays covering case studies in twelve countries, the anthology offers a broad review of student organizing against neoliberalization and more specifically, the privatization of higher education; intersectional and coalitional strategies imagined through these struggles; and alternative modes of knowledge production pre-figured in their organizing. Geographic and disciplinary breadth make the anthology a welcome addition to the growing corpus of (transnational) critical university studies.

Review of What’s the Use?: On the Uses of Use by Sara Ahmed (Duke University Press)

The last book in Ahmed’s terminological trilogy, What’s the Use investigates a term rooted in quotidian routine: use. Her previous books in this series, The Promise of Happiness (2010) and Willful Subjects (2014), interrogate happiness and the will respectively. Following her resignation from Goldsmiths University, What’s the Use highlights both the complexity of taking on use as a concrete project and the lasting effects of stopped university work. By leading the reader through an intellectual, philosophical, and educational history of “use,” Ahmed attaches “use” and the human experience to diversity work in the university. With student and faculty complaints as her evidence, Ahmed provides heart-breaking, anxiety-inducing, enraging testimonials of systemic oppression, ignorance, and abuse in the university setting. What’s the Use provides tangible practices for disrupting overused systemic oppression in a referential tome that can be used as both a study guide and a road map.

Persistence in Pedagogy: Teaching Failure, Empathy, and Citation

This self-reflexive essay addresses issues of teaching and pedagogy for social change in the Trump era. It places current teaching reflections in the context of the history of the corporatization of the university, systemic inequities in academia, and current political debates. It expands upon the structure of a teaching philosophy in order to share critical reflection, relevant sources, and pedagogical strategies drawn from the author’s experience teaching in dance departments.

Toward Alternative Humanities and Insurgent Collectivities

Introduction to Part II of the forum, Emergent Critical Analytics for Alternative Humanities. Here, emergent scholars respond to essays by J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Julie Avril Minich, and Jodi Melamed, each of whom elaborated on the alternative possibilities of dealing with the legacies of settler colonialism, new materialisms, disability, and institutionality in Part I, published in Lateral 5.1.

The Contexts of Critique: Para-Institutions & the Multiple Lives of Institutionality in the Neoliberal University

Response to Jodi Melamed, “Proceduralism, Predisposing, Poesis: Forms of Institutionality, In the Making,” published in Lateral 5.1. Tabares invites us to question the role of what he calls ‘para-institutions,’ such as corporations, in shaping and influencing the logics and investments within the university. As a counterpoint to these processes, he ponders the possibilities of seizing upon the elements of proceduralism in mobilizing forms of collectivity that can span across institutional contexts outside the academy.

Neoliberalism, Racial Capitalism, and Liberal Democracy: Challenging an Emergent Critical Analytic

Response to Jodi Melamed, “Proceduralism, Predisposing, Poesis: Forms of Institutionality, In the Making,” published in Lateral 5.1. Aho pointedly argues that studies of institutionality all too often substantiate what she calls neoliberalocentrism, which readily posits neoliberalism as the singular paradigm into narrating a teleological development of history. Instead, she echoes Kim and Schalk to articulate ‘crip-of-color materialism’ as an analytic that thickens understandings about global structures of inequity and fissures within them.

Introduction: Theory

Lateral’s Theory Thread offers essays that critically explore the relationship of carceral and educational institutions—but not as alternatives to one another as often has been assumed in various kinds of social activism. The authors of these essays, Sora Han, David Stein, Shana Agid, Gillian Harkins and Erica R. Meiners, assume the tightly knotted interrelationship of prisons and schools and instead address the question posed by Han: is there something, being affirmed in the identity or identification as a “prison abolitionist” today?

Full Employment for the Future

Who deserves what types of entitlements? On what grounds? In this moment of rampant and structural joblessness, there is an increasing critique of universities for their failure to create appropriate routes to employment for their graduates who are borrowing increasing sums of money to attend. Do these good students, who make, what President Obama has dubbed “good choices,” deserve jobs? If so, why only them? Or, with the extreme wealth of the U.S., should these good students, along with the bad, and everyone else, be entitled to a job or income? And what do employment rates for undergraduates have to do with the university anyway?

Pedagogy for Our Future

A liberatory UC, run by and for all the people, is not only possible—it is a critical part of a planetary youth movement that is enacting true democracy in public squares and parks. We have faith that the weapons at our disposal will allow us to play our part. We have faith that these weapons will allow us to peacefully tear down the old edifice and build this new university from the ground up. Our pedagogy is our main weapon, and on a daily basis, we see that it is neither blunt nor ineffective. These are our main pedagogical principles—intuitions more than ideologies, bonds more than guidelines, dreams rather than demands. These principles aim at cracking through the crumbling structure of the university at its base. Through these principles, we will take part in a guerrilla campaign to bring all of the people back into the university.

The Humanities and the University in Ruin

Mowitt’s essay puts before us in terms of work or, as Mowitt puts it, ‘re: working’ the work of study, scholarship, and research under the contemporary conditions of ‘biopolitical contol’ or neoliberal structural adjustment of the academy. Mowitt warns against reducing the issue of study to complaints of poor pay and poor working conditions and therefore holds the issue of the labor of study on a fine line between the refusal of the work of study altogether and the insistence on simply enjoying the study that we are required to do or paid to do. Mowitt is not denying the poor conditions under which so many of us work for insufficient pay in and outside the University; he rather is warning us about moving too quickly off the fine line between refusal and enjoyment of the required or paid work of study. He is arguing instead for the value of study as a labor of the negative. Mowitt then takes some elegant last moves to turn this return to the labor of the negative into the work of affirmation, thought affirming itself; he thereby moves beyond the dialectic and the Euro-centric Hegelian tradition of progress to affirm instead the immanent unfolding of mindfulness or thoughtfulness, an unfolding of an affective labor that bears within it the in-excess of measure, the yet-incalculable excess of the current calculability of value. This makes the re: working of study not merely a matter of the human or the humanities but of the technical/human medium we fast are becoming, and which we are coming to know we always have been, as has the University.

Response to “The Humanities and the University in Ruin”

In his response to Mowitt, Morgan Adamson sharply reminds us that working conditions and remuneration for work, not to mention layoffs, hiring freezes and slashing of benefits, certainly are pressing concerns. Offering a quick survey of some of the horrid details of the work expected of research assistants in science labs, Adamson also softens the distinction implied in Mowitt’s focus on the humanities as against the sciences.

Response to “The Humanities and the University in Ruin”

Adam Sitze addresses the technological transformation of the academy, emphasized critically by Mowitt, which have put us beyond the troubles of discipline or disciplinarity to something more abstract and technical.

Response to “Ante-Anti-Blackness”

In her response to Sexton, Christina Sharpe returns us to the psychopolitical necessity of such theorizing by pointing to her students who have organized again and again for black studies, and who in doing so each time also ask whether black studies ‘can ameliorate the quotidian experience of terror in black lives lived in an anti-black world?’ And if not, what should the relationship be between life and black studies, or between life and the University.

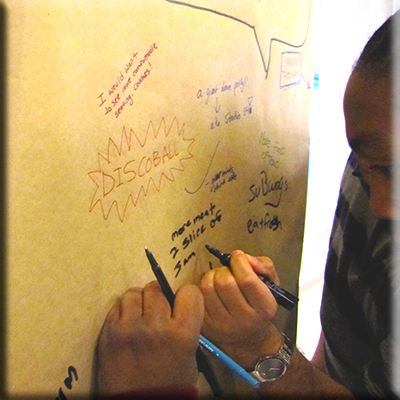

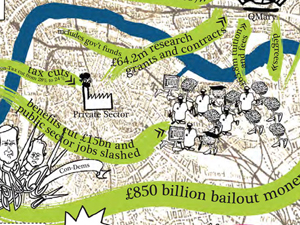

Countermapping the University

Appropriating the genre of the campus map, graduate students at Queen Mary University London and University of North Carolina Chapel Hill have produced a countermap of the university. Elegant in design, yet multi-purposed, their mapping of alternative uses and critiques takes the form of a poster-sized doubled sided print which locates the university within its larger societal force field (the map’s front side), and stages an arena for playing that field by means of a board game (which appears on the reverse side). In sharp contrast to the political geography of curricula intended to assimilate students to an already settled matter and progress-toward-a-degree, an unproblematic temporal beat measured by accumulated credit-hours, the critical cartographical work of this collective reallocates the energies of their seminars and research to produce alternate forms of knowledge and means for its legitimation.