Jose O. Fernandez’s Against Marginalization: Convergences in Black and Latinx Literatures is an innovative project that takes conversations about literary and cultural history in a new direction. Recognizing the efforts of Black and Latinx scholars in crafting distinct literary traditions and histories, Fernandez uses his book to argue for cross-ethnic literary studies and identify similarities between Black and Latinx traditions. This endeavor revolutionizes conversations about literary history of the United States and challenges narratives of exclusion and silencing. This book serves to show the importance of knowing the names of authors and artists, and the communities that fought for them, because they make up the fabric of US history. To learn those names next to Faulkner, Twain, Hemingway, Steinbeck, and Fitzgerald not only makes them part of American literary tradition but also spotlights their absence and exclusion in a way that expands the boundaries of “literary tradition.” This review takes seriously Fernandez’s project, which opens exciting avenues for cross-ethnic historic study while also examining opportunities for future study.

Keyword: Black studies

The Black Shoals Dossier

This dossier collects four reflections on The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (2019) with responses by its author Tiffany Lethabo King. This dossier is based on an American Studies Association 2021 roundtable organized by Beenash Jafri.

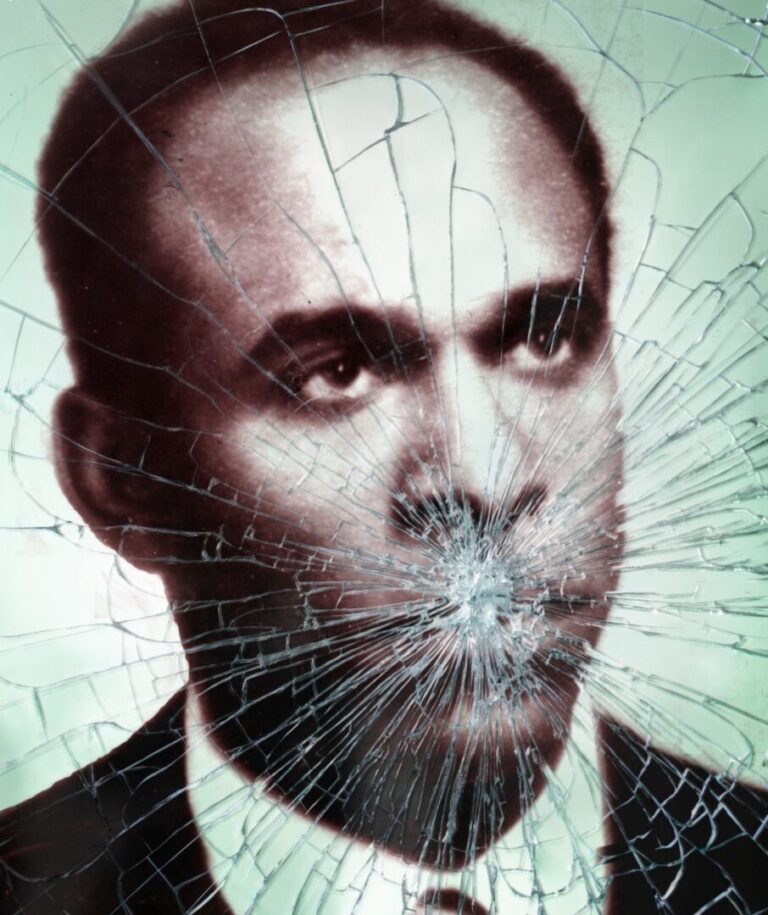

“Revolution of Thought and Action”: W. E. B. Du Bois’s World Search for Abolition Democracy

In recent years, scholars and activists have brought renewed attention to W. E. B. Du Bois’s concept of abolition democracy. Initially coined in Black Reconstruction (1935), to describe both a political movement and a democratic ideal, abolition democracy has been taken up theoretically by Angela Davis, Allegra McLeod, and others to describe the ongoing process of dismantling global capitalism’s political, racial, gender, and economic hierarchies, alongside the simultaneous creation of reconstructed social relations, institutions, and practices governed by universal democratic participation, instead of by force. This article suggests that Du Bois continues to draw on abolition democracy as a conceptual framework in his post-Black Reconstruction work. Tracing the outlines of this framework in his unpublished manuscript A World Search for Democracy, I demonstrate how for Du Bois, the question of democracy remains fundamentally tied to the ongoing legacies of slavery. As he continues to draw on the Reconstruction era as an historical example, Du Bois gives further shape to the idea of abolition as a process in the present (rather than an event in the past). In doing so, he recuperates the unfulfilled promise of abolition democracy as a theoretical and practical model for considering alternatives modes of citizenship beyond the material, ideal, and embodied limits of liberal bourgeois democracy. Accordingly, I argue, in World Search, we can see the outlines of abolition democracy as a three-fold project: political-economic, epistemic, and affective. Each section of this article sheds light on one of these dimensions, drawing on theoretical models from Nancy Fraser, Sylvia Wynter, Sara Ahmed, and Dylan Rodríguez. By thus abstracting the concept of abolition democracy further from the historical movement analyzed in Black Reconstruction, I propose that Du Bois’s World Search offers lessons that can inform abolitionist theory and praxis today.

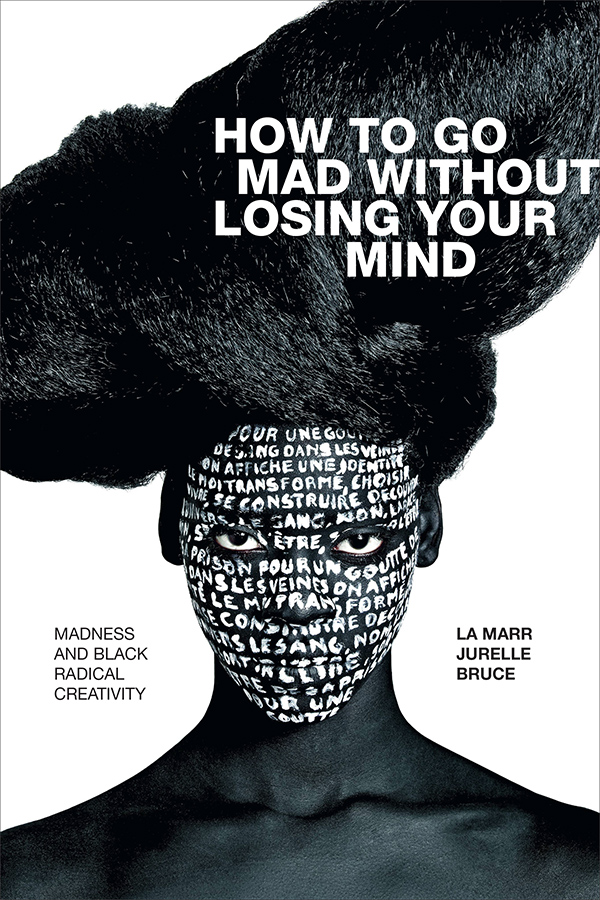

Review of How to Go Mad without Losing Your Mind: Madness and Black Radical Creativity by La Marr Jurelle Bruce (Duke University Press)

How to Go Mad without Losing Your Mind offers a poignant study of what author La Marr Jurelle Bruce calls “mad methodology,” extending care and consideration to Black artists historically, fictionally, and contemporaneously rendered mad by oppressive anti-Black capitalist discursive practices. Reflecting on the creative practices of Buddy Bolden, Nina Simone, Lauryn Hill, and Dave Chappelle, among others, Bruce provides a clear-cutting analysis of the ways normative cultural logics work to figure Black art and protest as inherently mad.

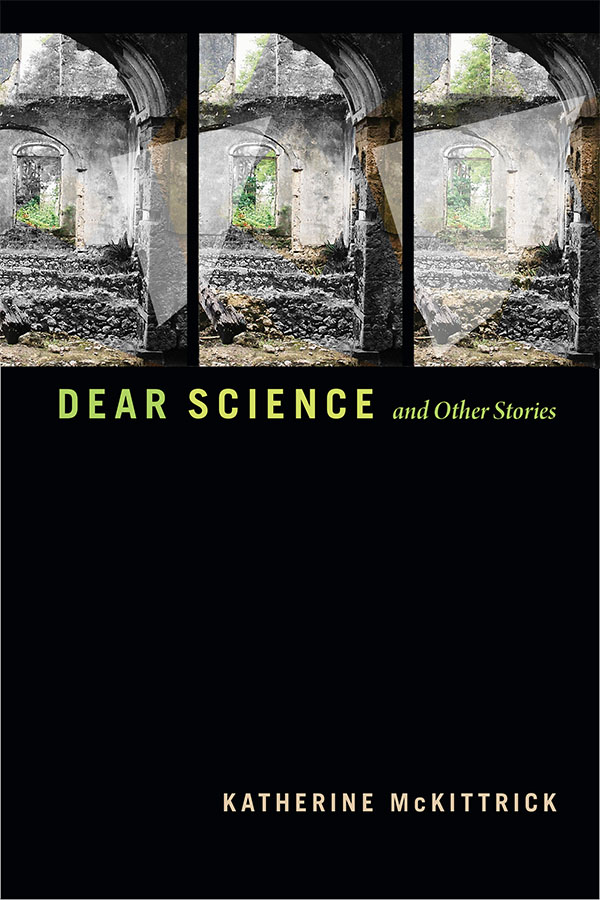

Review of Dear Science and Other Stories by Katherine McKittrick (Duke University Press)

With Dear Science and Other Stories, Katherine McKittrick does the work of liberation and enacts new ways of being. Building on her previous studies, this collection engages in a story-sharing, collaborative praxis that emerges from a “black sense of place.” McKittrick’s Black and anti-colonial methodologies are “rebellious,” “relational, intertextual, and interdisciplinary”—thereby “breaching” the “recursive,” “self-replicating” logics of “our present order of knowledge” (44, 2, 23, 163). Dear Science invents, reinvents, and reimagines “being human as praxis” through an aesthetic practice of deciphering theoretical texts, photographs, sounds, dance, and song (159). Illustrating her commitment to Black intellectual life, McKittrick writes, listens, and feels in communion with other creatives. In so doing, McKittrick skillfully bursts open the gatekeeping conventions that limit thought, and challenges readers to question what they think they know.

“A Program of Complete Disorder”: The Black Iconoclasm Within Fanonian Thought

This essay examines the scholarship of revolutionary theorist Frantz Fanon and the debate surrounding his conception of decolonization and “new humanism.” Across a multitude of fields, Black and cultural studies among them, Fanon has been heralded as an iconic thinker who offers us a path toward an alternative humanity. Working against the grain of this popular form of Fanonism, I suggest that there is a Black iconoclasm—a deep desire to unsettle the very rendering of a systematic path toward decolonization—that pervades Fanonian thought. Accordingly, the essay examines and unsettles various forms of Fanonism by suggesting that their teleological narratives of redemption ultimately end up serving anti-Fanonian pursuits. Through an extended meditation on Fanon’s claim that decolonization is “a program of complete disorder,” I explore what it might mean to embrace a Black iconoclastic approach to Fanon and the pursuit of Black liberation.

Review of Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man by Joshua Bennett (Harvard University Press)

Reading a robust archive of twentieth and twenty-first century African-American literature, Joshua Bennett’s Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man lays the foundations for rethinking kinship and relation between humans and animals.

From Gwangju to Brixton: The Impossible Translation of Han Kang’s Human Acts

This article theorizes the relationship between trauma and translation through a close reading of Han Kang’s Human Acts (2016) and its complex narrating of the Gwangju Democratization Movement of 1980. I engage with the novel through scholarship on state-sanctioned violence, the politics of memory and Korean and Black literary and cultural studies. I do this to consider how the massacre of Gwangu’s residents by their own government is made possible by earlier histories of occupation and imperial violence in the Korean peninsula. I then turn to the Korean edition of the novel to address what emerges outside of the English translation. Here, I rely on my own language skills to read, translate and direct attention to what is lost in Deborah Smith’s published translation of Han’s novel. Specifically, I argue that Smith’s version of Human Acts actively works against Han’s subversive articulation of the elusiveness of subjectivity, the rending of the world vis-à-vis violence, the possibilities afforded by opacity and the dilemma of what it means to write about “one’s own” historical trauma. In an attempt to reflect critically on what it might mean to live in the ongoing ripples of such traumas, I offer a text that blurs autobiography, travel writing, Black Studies, and literary analysis, crafting something that may be situated under the aegis of cultural studies and alongside what Gloria Anzaldúa names an autohistoria-teoría and what Crystal Baik calls a diasporic memory work.

Review of The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies by Tiffany Lethabo King (Duke University Press)

In this ambitious first book, Tiffany Lethabo King disrupts what she sees as settler-colonial studies’ tendency to privilege the settler/conquistador as the ethical subject of Western theory. To do so, she undertakes the urgent work of considering historical, ceremonial, imaginative, and theoretical ways that Native and Black studies intersect and overlap within the North American context. Drawing in particular upon Afro-pessimism (for instance Frank Wilderson, Saidiya Hartman, Katherine McKittrick, Alexander G. Weheliye, and Sylvia Wynter) as well as Native studies’ refusal of sovereignty as a political, ethical, and material formation (Audra Simpson, Glen Coulthard, Jodi Byrd, and Andrea Smith), King joins the likes of Tiya Miles in seeing as insufficient any account of settler colonialism or Western humanism that does not consider how Black and Native epistemologies and histories intersect.

Review of Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval by Saidiya Hartman (W. W. Norton & Company)

This review considers how Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval poses a challenge to the reader. The invitation is to stay immersed within the everyday lives of Black women and girls, who navigated the terrains of New York City and Philadelphia at the turn of the twentieth century, without fleeting into spectacle or pathology. One may assume that such is an effortless proposition that is carried simply by the desire to think about Black women. However, Hartman tacitly demonstrates that a tremendous counter-historiography must be amassed to write the stories of those who have been underwritten by the tales of politics, great Black men, shining Black starlets, or the widely pathologized Black female figure. Thus, Wayward Lives weaves together a beautiful narrative of the social upheaval of Black women and girls at the dawning of Northern urban space, and what would later become known as the Black ghetto. At the same time, Hartman exposes the limits of the official record and narratives which relegate the lives of Black women as tertiary, as opposed to an integral political history in its own right.

Review of Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction by André M. Carrington (University of Minnesota Press)

André Carrington’s ‘Speculative Blackness’ is a novel approach to the consumption of race representation in media. Carrington explores how Blackness is manufactured, consumed, and transformed through the speculative fiction genre across multiple 20th and 21st century mediums. Traditional media of comic books and television shows reveal the marginalized status of Black figures however, these media do not exist in a vacuum. The consumption of speculative fiction is a transformative process for the original content, which consequentially produces amateur media due to a long-established history of fan interaction. Black representation is characterized as the exception, not the rule, in traditional production, but fan consumption reconfigures these notions. Ultimately, Carrington’s work is an innovative dialogue regarding a genre that creates worlds speculating on what could be. Speculative fiction breaks down preexisting notions of our reality and creates worlds with entirely new expectations and interactions. With the creative liberty of the genre, Carrington casts Black representation as a consumed media but also an imaginative effort.

Ante-Anti-Blackness: Afterthoughts

Sexton sees to ask again about the tension between what has been coined afro- pessimism and black-optimism or what black intellectuals long have discussed as life after or in the social death of slavery. Taking up the arguments of a number of these intellectuals, especially those most recently offered by Fred Moten, Saidiya Hartman and Frank B. Wilderson, Sexton proposes that we stay on the fine line, here between optimism and pessimism, between life and death. For the optimists, the refusal of this identification is an insistence on ‘black agency being logically and ontologically prior’ to a social order that is anti-black, prior to a governance that turns blackness criminal and therefore calls for an affirmative politics of fugitivity. On the side of pessimism, is the longue duree of social death in the ongoing history of slavery and anti-black racism, if not racism generally. It is blackness theorized as ‘a structural position,’ ‘a conceptual framework,’ and ‘a structure of feeling.’ On the fine line between this pessimism and this optimism, Sexton argues that a question arises as to how to approach this social life in social death while enabling new means of thoughtfulness or mindfulness in living, in studying, in the University and elsewhere. Sexton borrowing from David Marriott argues for ‘the need to affirm affirmation through negation…not as a moral imperative…but as a psychopolitical necessity.’

Response to “Ante-Anti-Blackness”

In her response to Sexton, Christina Sharpe returns us to the psychopolitical necessity of such theorizing by pointing to her students who have organized again and again for black studies, and who in doing so each time also ask whether black studies ‘can ameliorate the quotidian experience of terror in black lives lived in an anti-black world?’ And if not, what should the relationship be between life and black studies, or between life and the University.