In response to Zamora and Jäger’s intellectual history critique of my original essay, I reiterate the methodological necessity of grounding a historical study of basic income in a Marxist framework that considers both the organic and conjunctural. This approach illuminates the complexities of basic income as common sense under capitalism while illustrating the limits and opportunities for Left organizing around the idea of basic income.

Articles by David Zeglen

David Zeglen is a PhD candidate in the Cultural Studies program at George Mason University. For his dissertation, he is researching the applicability of Trotsky’s concept of uneven and combined development as a theory of cultural globalization. He is currently co-editing a special issue of Celebrity Studies with Neil Ewen on right-wing populist celebrity politicians in Europe due out in 2020.

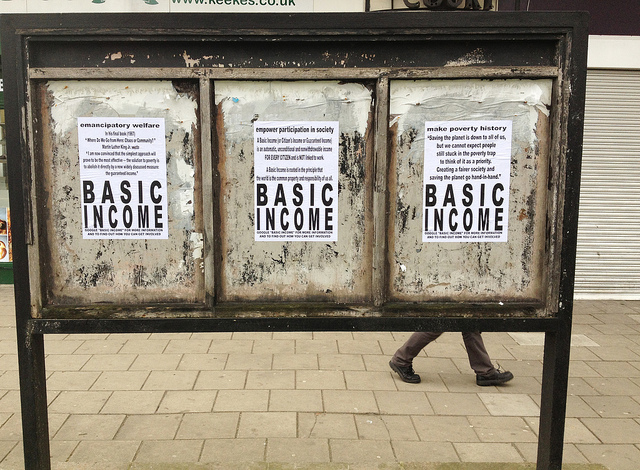

Introduction: Political Economies of Basic Income

Basic income is an idea almost as old as capitalism itself, appearing very early in the course of its historical development. The emergence of the idea of a basic income in the first few centuries of capitalism’s development in England became inextricably linked to economic crisis. Unsurprisingly, interest in basic income plans have resurfaced yet again in the post-2008 conjuncture. Current debates about basic income often invoke the framework of a morality play about personal responsibility, work ethic, and frugality that obfuscate organic features of the capitalist social formation, such as economic crisis. Therefore, this forum returns to the Marxist approach to answer the persistent questions that basic income provokes, and to help enlarge the Left debate on basic income that exists on the margins of public discourse.

Basic Income as Ideology from Below

Most Left critiques of basic income assume a model of “false consciousness” on the part of basic income advocates. These critiques do not account for how desires for a basic income may also come from the material inversion of social relations that occurs under capitalism. Considered from the vantage point of fetishism and common sense, basic income demands appear rational rather than the product of false consciousness, which in turn informs how the left should organize “good sense” to build a hegemonic bloc.

Review of Foucault and Neoliberalism, edited by Daniel Zamora and Michael C. Behrent (Polity)

Foucault & Neoliberalism modestly argues that Foucault’s project, particularly after May 1968, bore striking similarities with neoliberalism. Although scholars have debated this issue since at least the French publication of The Birth of Biopolitics, Foucault & Neoliberalism shows that, since the English publication of the same lecture series in the inauspicious year of 2008, the American university has increasingly deracinated Foucault from his French context and thereby misread his attitude toward neoliberalism. Thus Foucault & Neoliberalism, an English translation of Zamora’s previous anthology in French, Critiquer Foucault, seeks to revive the debate—and has done so in the pages of Jacobin magazine thus far—by situating Foucault back into his proper historical milieu.