Delores Phillips and Cultural Studies Association’s Globalization and Culture Working Group Co-Host Kathalene Razzano discuss Disorienting Politics: Chimerican Media and Transpacific Entanglements (University of Michigan Press, 2024) with author Fan Yang, along with writer and historian Mark Tseng-Putterman. This podcast is accompanied by a scholarly commentary by Marcus Breen.

Keyword: COVID-19

Chimerica: Disorienting Politics

Delores Phillips and Cultural Studies Association’s Globalization and Culture Working Group Co-Host Kathalene Razzano discuss Disorienting Politics: Chimerican Media and Transpacific Entanglements (University of Michigan Press, 2024) with author Fan Yang, along with writer and historian Mark Tseng-Putterman. This podcast is accompanied by a scholarly commentary by Marcus Breen.

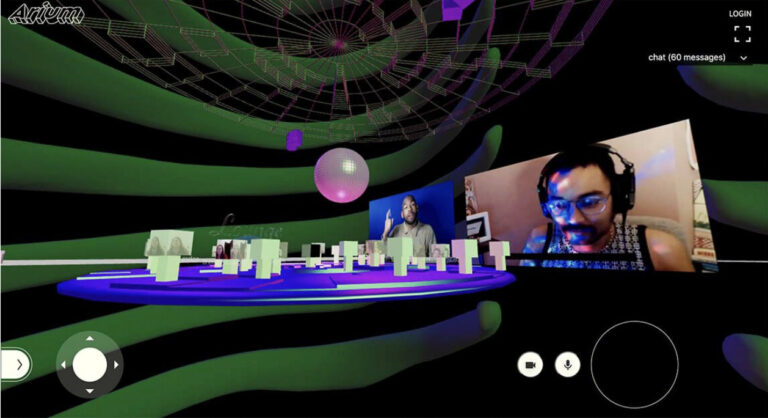

Remote Access: A Crip Nightlife Party

Remote Access is a disability nightlife event informed by disability history, technology, and artistry. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a collective of disabled artists and designers created an event to showcase how disabled people often participate in social life from our homes and beds. This contribution offers a living archive of the party and its evolution, as the planners created protocols for collective access through methodologies such as participatory audio description and live description of musical sound. We discuss how each new event offered opportunities for designing new practices based on disabled knowledge and expertise. As a result, the series of Remote Access nightlife parties became an ongoing opportunity to develop iterative accessibility protocols and community standards for remote/digital participation.

Corona Look of the Day: Social Media Posts About Disabled Beauty and Resistance in the Time of COVID-19

The authors created a photo and essay series entitled “Corona Look of the Day.” Each day we took photos of outfits paired with colorful makeup and inspired text descriptions about the beauty in disability. These posts were formulated as resistance to the eugenic discourse pervading the early days of the pandemic that argued disabled and elderly deaths were acceptable and probable. In contrast to this bleak assessment, this artistic series sought to affirm disability through uplifting portraiture.

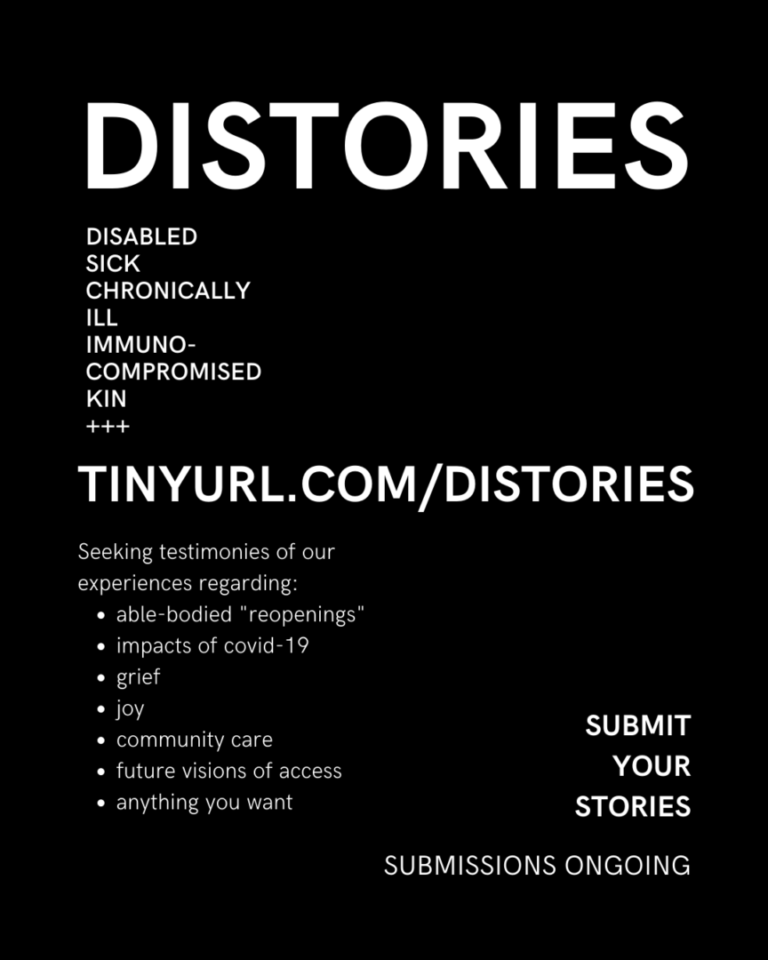

DISTORIES

DISTORIES is a small open-source and open-access Instagram zine project, gathering testimonies from disabled contributors. This project began in the context of the summer of 2021, as mask mandates and general precautions around COVID-19 were being relaxed. Each chapter of the zine is introduced by a question, framing stories and snapshots of experience as well as demands, affirmations, and dreams shared by contributors. The project was stewarded by geunsaeng ahn from September 2021 to July 2022.

The Dedication: Leaving Evidence of Life, Death, Care, and Confinement During COVID-19

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic exploded and nursing homes rapidly became overwhelmed with disease, death, and despair. During this time, I learned Sylvia, an old woman with dementia I had befriended, was one of the many old and disabled people confined in nursing homes who did not survive. In this reflective and part personal, part scholarly essay, I leave evidence of and for Sylvia and the nearly 200,000 old and disabled people and care workers who contracted COVID-19 and died within the confines of neoliberal, profit-driven long-term care institutions. Disability justice activist Mia Mingus writes, “We must leave evidence. Evidence that we were here, that we existed, that we survived and loved and ached.” Leaving evidence is a political act, a form of resistance in an ableist word. And yet leaving evidence is particularly challenging in the context of dementia, care, confinement, and death—making it even more important, more urgent. Building on Ellen Samuels’ assertion, “Crip time is grief time,” I consider how mourning Sylvia and countless other nursing home deaths, interwoven with my own experiences of distress, yet also solidified my need to survive, might leave evidence and keep working toward an abolitionist future—one in which old and disabled women like Sylvia, like my future self, might thrive.

Only Together, We Flourish: The Importance of Friendship and Care in Navigating Anti-Asian Hate and Shielding During COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic and the response of the government of the United Kingdom have exacerbated deep-seated inequalities. People of color and disabled people have been disproportionately impacted during the pandemic. This essay has two authors, Sophie, a white disabled academic from England, and Denise, an Asian music therapist from Hong Kong; we are friends who live in Bristol. By examining our understanding of the pandemic through our lived experiences and identities, we provide transparency for engaging with our individual and shared perspectives. We use Mia Mingus’s concept of access intimacy to characterize our friendship as one which prioritizes accessibility and a deep understanding of each other’s realities whilst respecting and learning from our differences. We explore the idea of vulnerability and what it means to be made vulnerable during COVID, as well as the notion of ungrievability. Through engaging the concept of embodied belonging we address care as a necessity in response to all the ways in which this pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated vulnerability, ungrievability, and challenges to finding a sense of belonging. We demonstrate solidarity, empathy, joy, love, respect, and a deep reverence for each other and our journeys through hostile environments, providing a counterpoint to the neoliberal structures of oppression as we find ways to live, create, and flourish.

600 mg of Lithium, Quarantine, and “Third-Spaces”

With a mix of prose, critical reflection, and an accompanying series of drawings inside a daily planner, this intimate essay reimagines multiple conceptions of “space” in relation to different kinds of sickness and wellbeing. Meditating on COVID-19 quarantine spaces and bipolar disorder mood/mind-spaces allowed me to discover messied “third” spaces that explore margins, and complicate ideas of boundaries and binaries. Doing so allowed me to think through new possibilities of healing, restoration, and intimacy when we talk about mental health. I offer up my personal account of a young female Asian American graduate student navigating a ten-year struggle with clinical bipolar disorder, and the personal experiences of “madness,” relapse, and recovery during the winter and spring of 2021. I reflect on my daily routines inside my 800-square-foot apartment and my growing realization that prevailing ideas of “space” are incomplete and contradictory—but can be replete with futurities and learning possibilities. Fittingly, this creative piece does not endeavor to offer any neatly packaged analysis or solid conclusions. Instead, I present one account of grappling with mental illness under extraordinary circumstances and hope it can speak to individual and collective discussions on mental health, disability, and spatiality.

For Graduate Students, When the Sadness is Unbelievable: How to Research and Write If We Must When the World is on Fire

This essay is a meditation on the place of grief in graduate student life, an accounting for the ways that the pandemic has shaped research and the work that disabled graduate students have had to do to stay afloat. I begin by meandering through the grief of a family bereavement into the range of other kinds of crip grief that emerged at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thinking with grief across scales, I ask the following questions: what might it mean to research and to write when our fields of inquiry shift even as they are being studied? How might we hold on to hope as a political practice even as undercurrents of grief work to wash it away? Where and how might we find and work with methodologies and practices that prioritize our embodied experiences during precarious, difficult times? Drawing on Melissa Kapadia’s work on chronic illness methodology and Gökce Günel, Saiba Varma, and Chika Watanabe’s manifesto for patchwork ethnography, I attend to the place of patchwork as a survival strategy for and beyond field research. Ultimately, this essay works with grief’s non-linearity, patching together memories and experiences to document one experience of the early years of the pandemic as means of making the aloneness of our graduate journeys less commonplace.

Introduction: Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry

“Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry” takes up a thread from disability justice writer, educator, and organizer Mia Mingus to assemble an archive that “leaves evidence” and captures experience emergent from crip lives and life in the pandemic. The need to gather, hold space for, and preserve evidence—of our angers, our fears, our griefs, our joys, our pleasures, our communities, and our lives—has, for many of us, never felt more urgent. In this editorial introduction to the first installment of the special section of Lateral, “Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry,” we narrate project origins in response to pervasive and obfuscating crisis rhetorics, feelings of indignation, and a desire to gather and preserve evidence of crip life and crip knowledge from within the context of the pandemic. “Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry” offers a unique digital archive that brings together creative and scholarly reflections to document the experiences of disabled people during the COVID-19 pandemic. The collection includes a multimodal introductory roundtable; multimedia projects; digital renditions of sculptures, masks, fiber arts, and zines; critical interrogations of pandemic politics and policies; and theorizations of crip sociality. This editorial introduction is our brief overview and invitation for readers to travel through spacetimes, bear witness to, and be cared for by this tapestry, archive, collection.

Crip Pandemic Conversation: Textures, Tools, and Recipes

“Crip Pandemic Conversation: Textures, Tools, and Recipes,” brings together experts whose scholarship, curation, organizing and artistic work centers crip insights and creativity to reflect on the work that “Crip Pandemic Life: A Tapestry” undertakes. Margaret Fink, Aimi Hamraie, Mimi Khúc, and Sandie Yi each discuss how the pandemic impacted their work, and they join section co-editors Alyson Patsavas and Theodora Danylevich in discussing the tapestry’s content. Their conversation pulls out some of the most salient threads of the work: smallness, grief, care, community-building, tenderness, and pandemic coping tools. “Crip Pandemic Conversation: Textures, Tools, and Recipes” includes an unedited video recording of a Zoom roundtable session, a lightly edited text version of the conversation, and a glossary of terms that appear in the discussion, as a contextualizing access tool located at the bottom of the document. In choosing a preferred way of engaging with the content, we invite readers to consider, as the roundtable participants themselves do, how access (transcripts, zoom recordings, and captions) produces its own caring archive and knowledge-making practices.

Coalition-In-Progress: Found Poetry Through Phone Calls with People Labelled/With Intellectual Disability During the COVID-19 Pandemic

For institutional survivors and their younger peers labelled/with intellectual disability, the COVID-19 pandemic and its related lockdowns carry over past experiences under government-directed isolation and mandatory medical interventions. The sudden convergence of past and present necropolitical ableism in labeled persons’ lives colours this crisis, as we—a group of survivors, younger labeled people (who have not lived in institutions), and researcher/allies—attempt to simply stay in touch amid digital divides that cut off our once vibrant, interdependent in-person activities. No longer able to gather, and with limited Internet (or no) access, we resist social abandonment through phone calls. During phone conversations we discuss the affective contours of this time: grief over the past, loss of agency, restrictive rules in group homes, the dynamics of protest, fear sparked by public health orders, and a mix of anxiety and hope about the future. Taking this telephone-based dialogue as evidence of our lives in these times, we present a brief body of collectively written found poetry, a form of poetic inquiry composed of phone call snippets. This piece, coauthored by twenty members of the “DiStory: Disability Then and Now” project in Toronto, Canada, offers a snapshot of coalition-in-process, keeping in touch amid a crisis that threatens our togetherness and—for some more than others—our lives. Following Braidotti, we couch this found poetry in a brief commentary on our slow, in-progress attempt to “co-construct a different platform of becoming” with one another amid a divergence of historical and contemporary inequities.

How Do You Grieve During an Apocalypse?

This essay is a rumination on loss during the pandemic—not only the physical loss of loved ones but the loss of experiences and time. Focusing specifically on the death of my aunt, Joyce Dana Apostole, I reflect on what it means to mourn, not only as an individual but as a collective. Through the retelling of significant moments in Joyce’s life and recalling our relationship, I consider the questions: How do you navigate grief when you cannot congregate with others? How is that grief compounded by institutional failures—medical, governmental—and informational lack? And how does social response to individual and mass loss reflect philosophies and policies that (continue to) devalue—and prove detrimental to—the lives of disabled people? Ultimately, this essay is not only a reflection on grief, but it is also a eulogy, an opportunity to fully recognize my aunt and her complex history, a life shaped by illness and disability in ways that counter popular narratives of recovery and overcoming. It is an archive of not only what was, but what wasn’t, necessary documentation within a culture in which “return to normalcy” can become synonymous with forgetting.

Roundtable: Crip Student Solidarity in the COVID-19 Pandemic

This roundtable shares the first-hand experiences of five crip, disabled, Mad, and/or neurodivergent doctoral students navigating academia in so-called Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. While we discuss and theorize our experiences of ableism, structural oppression, and inaccessibility in the academy, we also highlight the world-building experiences of solidarity that have emerged for us in crip community, and in particular among fellow crip graduate students. We consider the ways that crip students open up potential for new ways of learning and being by challenging dominant norms of academic productivity, and we also consider what is lost when these students are pushed out of academic spaces. By engaging in “collective refusal” of the conditions that harm disabled and otherwise marginalized students, new possibilities emerge for connection, community, and radical change. The virtual conversation transcribed here took place over Discord, email, and Google Docs in autumn of 2021 and early winter 2022. This piece embraces multi-tonality, that is, a range of different voices and ways of writing, speaking, and communicating. It is a conversational piece that intentionally blends varied approaches to knowledge-sharing: polemic, citationally-grounded, and personal anecdotes drawn from our diverse lived experiences. There are a number of different themes woven throughout the text, including anecdotes and personal history, solidarity, ableism in the academy, pessimism/failure, community/interdependence/intimacy, and utopia/futurity/demands for the future. While not intended to provide policy guidance or step-by-step instructions for changing academic culture, we also begin to sketch out some of our dreams for an alternative future for disabled scholars. We discuss imagined futures and possibilities, and ask, is a truly crip and/or accessible academic institution possible?

Overwhelmed

The isolation, stress, and uncertainty fueled by the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged our collective mental health. For people with preexisting psychiatric disabilities, these repercussions are further magnified. This is particularly true for individuals who have experienced involuntary confinement in “corrective” facilities. For survivors of institutional abuse, the gross restriction of movement generated by the quarantine and lockdowns replicates the systems of total control to which they have previously been subjected. Facing an uncertain future and lacking access to community support systems, many survivors have been forced to improvise mechanisms to relieve traumatic symptoms on their own. While these self-soothing mechanisms can provide relief during moments of acute distress, they may be ultimately destructive and exacerbate long-term symptomatology. This artwork is an expression of overwhelm and the conundrum faced when survival strategies that meet immediate needs threaten long-term well-being.