Delores Phillips and Cultural Studies Association’s Globalization and Culture Working Group Co-Host Kathalene Razzano discuss Disorienting Politics: Chimerican Media and Transpacific Entanglements (University of Michigan Press, 2024) with author Fan Yang, along with writer and historian Mark Tseng-Putterman. This podcast is accompanied by a scholarly commentary by Marcus Breen.

Issues

Editors’ Introduction: Imaginary Futures

This issue introduction reflects on the upcoming 2025 Cultural Studies Association Annual Conference theme, “Imaginary Futures,” and cultural studies futures. This issue contains several articles that address the “presencing” of possible futures, whether through Black popular culture; digital laborers, tech workers and online sex workers; cannabis commodity aesthetics and working-class Black and Latinx life in contemporary California; or racialization of the K-pop band BTS. This issue also features several articles in the special section, “Political Economy and the Arts,” edited by Katerina Paramana, contributions to “Aporias,” edited by Joshua Falek, and the Positions podcast, and six book reviews.

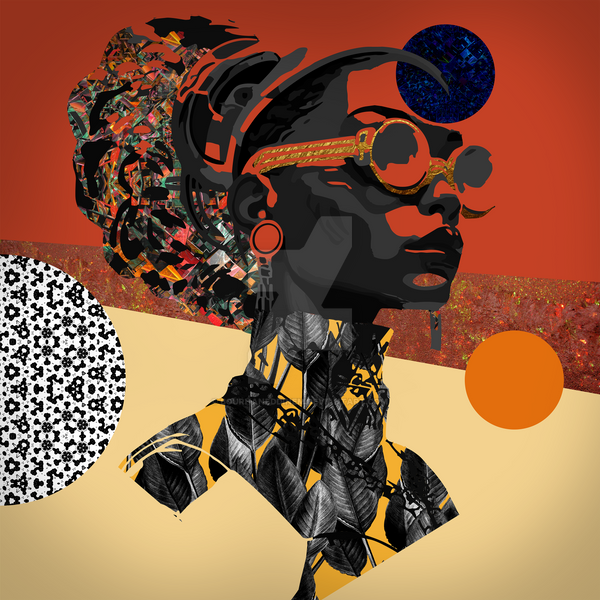

Everyday Black Futurity in Popular Culture

Black popular culture draws on everyday Black experiences to create ideas of futurity. There are well known examples of Afrofuturism, such as the Black Panther films, as well as the music of George Clinton, Sun Ra, Janelle Monáe, and Erykah Badu, which offer profound versions of Black futures. In addition to these essential examples, some artists are not always explicitly named as such and incorporate robust conceptions of futurity and speculation into their work. This article examines the performances of Missy Elliott, Megan Thee Stallion, and Cedric the Entertainer. It argues that through their embodied performance practices that cite Black life, they create persuasive critiques of the present and move forward ideas about the future. In addition to using futuristic settings and themes, their embodiments work to put forth compelling ideas of speculation. These artists employ notions of the posthuman, a speculative figure that interrogates the category of the human through embodied gestures, dances, and other movement styles. The examined performances challenge notions of respectability established through white norms and neoliberal disciplinary mechanisms that police and harm Black bodies and render them outside of humanness. Specifically, Missy, Cedric, and Megan’s performances are rooted in concepts like ghetto, ratchet, and hood, which push back against US society’s notions of the human as defined through the respectable laboring body that is also read through the standard of whiteness. The twin dynamic of the human and posthuman provide critiques of the historic and layered expansiveness of anti-blackness while also centering Black people’s joy, pleasure, desire, and freedom. As such, these performances proffer notions of the present and future, the human and the posthuman. The force and effectiveness of these artists’ performances reside in how they draw from the everyday ways Black people articulate ideas of radical futurity.

The Incubator and the Interregnum: Theorizing the (Work)Places of Class Struggle

Labor landscapes of post-Fordism are commonly characterized by fragmentation, fracture, and atomization, with platformization as the latest abstraction of a workplace that is everywhere and nowhere. The period following the 2008 financial crash has been posed as an interregnum where the exposed contradictions of neoliberalism have not yet ousted this order, while multiple actors jostle to grasp the reins. In this paper, I propose a focus on the cultural practices of place-making in theorizing contemporary class struggle with reference to two groups of digital laborers: tech workers and online sex workers. Taking the incubator—a place of pooled resources for companies in-the-making—as a jumping off point, I consider the interrelations, differentials, and potentials for class (re)composition when the distinction of work from life is as blurred as it is distinguishing. From an autonomist perspective and looking to collectives such as the Tech Workers Coalition and Hacking//Hustling, I unpick the “common sense” of a placeless platformed capital to explore the multiplicity of the “workplace,” what counts as “work,” and which places enable the imagination of otherwise. As visions of the “future of work” abound I ask, how can research under the umbrella of cultural studies support and co-create points of intervention—places of aggregation—in the interregnum?

Cannaboom: Race and Labor in California Cannabis Cultures

Encouraged by state requirements for prepackaging, Black and Latinx producers and distributors of legal cannabis in California have developed novel, symbolically and socially significant forms of marketing. Black and Latinx cannabis industries have developed their own “commodity aesthetics,” using product packaging, live events, and social media to entice buyers with a combination of beautiful sights, smells, textures, signs, and symbols that represent the contradictions of working-class Black and Latinx life in contemporary California. Black and Latinx cannabis popular cultures combine images of freedom and transcendence with depictions of the low wage jobs that many Black and Latinx people work. This is because, rather than an impediment to work, cannabis consumption is a kind of support for or accessory to labor. Many consumers use cannabis to dull the tedium and pain of labor and to sustain them throughout the workday. This essay provides a critical overview of Black and Latinx cannabis marketing in California, and its targeting of working-class consumers of color. While I discuss several examples, my central case study is the successful Black and Latinx cannabis distributor Teds Budz. I draw on interviews, ethnographies of live cannabis events, and visual studies of cannabis packages and social media, arguing that seemingly “escapist” qualities in cannabis culture critically foreground the material limits of the world from which Black and Latinx workers are trying to escape. Cannabis commodity aesthetics, I conclude, promise people of color an exit from the drudgery of work that can also tighten their ties to low wage jobs.

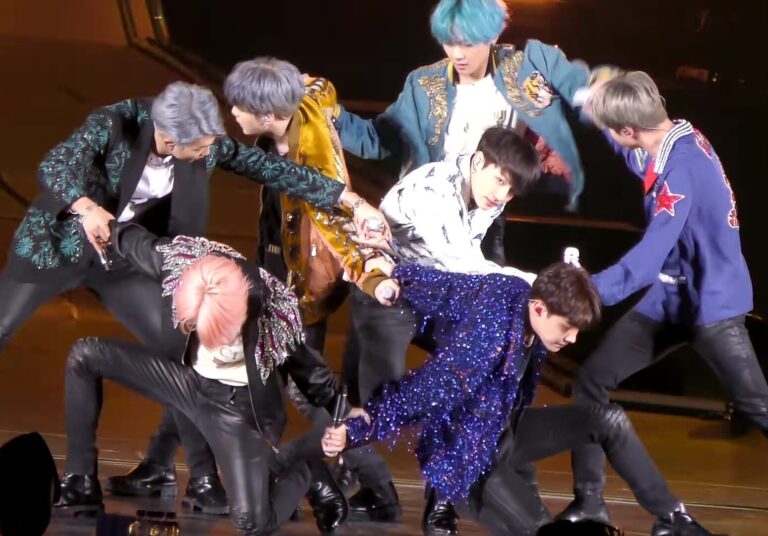

BTS and the Labor of Techno-Orientalism

This article makes the case that the discourse around K-pop supergroup BTS and their fans—known as ARMY—marks an intersection between techno-Orientalism, the abstraction and demonization of Asian labor, and Korea in the US imperial imaginary. BTS exemplifies what I suggest is a contemporary form of Asian racialization that emphasizes the Asian figure as embodying a series of seeming contradictions between the synthetic/mechanistic and the undeveloped/primordial. BTS reveals the ways that these threads of racialization do not contradict but rather complement each other, explaining how narratives marveling at the group’s technical proficiency/synchronicity/productivity can exist side by side with suggestions that their musical output is the result of a labor that is denigrated because it is perceived as being mechanized, abstract, and devoid of the qualities of artistry and creativity exclusively associated with Western modernity.

Introduction – Performance and Political Economy: Bodies, Politics, and Well-Being

In this article, Katerina Paramana introduces Lateral’s special section, “Political Economy and the Arts,” and its first set of articles, “Performance and Political Economy: Bodies, Politics, and Well-Being,” and provides the rationale and context for this section’s topic. In the face of a multiplicity of world-wide problems and suffering, this special section aims at a reinvestment in desire for change in order to resuscitate and reinvest in hope. The articles therein provide insights into the current relationship between politics, human and non-human bodies, and their well-being (and why it is necessary we take action to change it) which might help us steer the wheel before we drive off the cliff.

The Problems with the Critique of Political Economy in the Arts

This article attempts to offer a systemic discussion about the paradigm shift away from the neoliberal Washington consensus and its ramifications for the worlds of performing and visual arts. The article first provides an overview of discussions of political economy in the arts, in which the typically speculative arguments are contrasted with sociological and historical knowledge which reveals a limit to them. The article then describes contemporary political economy in the era of post-globalization and makes a few proposals on how the arts can think through it.

Racial Capitalism, Refugee Adjudication, and the Performances of Zama Zama

This essay investigates the category of the refugee as an instantiation of racial capitalism. To illustrate this conjunction, it first examines international law that defines refugees and, then, looks to specific national jurisprudence that accords different recognition to them. The national contexts discussed are the United States, given that the racial discourse there serves as a ground for the most widely known theorization of racial capitalism via Cedric Robinson’s book Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, and South Africa, where racial capitalism was first coined. Robinson’s work is briefly elaborated in relation to subsequent scholarship that has engaged and extended the concept of racial capitalism, in relation to the particularities of South Africa racialization, and in relation to zama zamas (unregulated miners, often perceived as foreigners who threaten the Rainbow Nation’s stability in various ways). Given limitations of space, the essay uses the overview of juridical regimes and the excursus on Robinson to rethink the category of refugee. Zama zamas and the history of the South African mining sector as it informs understandings of race are posited as a fruitful direction for further research because these phenomena help to extend the entwinement of race and refugee and the implications of Robinson’s text for understanding refugees anew.

“A Currency of Happenstance”

Commissioned by Manchester International Festival, The Find (2023) was a participatory art project by conceptual artist Ryan Gander. It distributed non-monetary coin in public space to create what Gander termed “a currency of happenstance,” engaging chance procedures and choice. This essay discusses The Find’s participatory aesthetics and ethical claims, asking what its engagement with coin might elucidate regarding continuities and changes in cultural and economic life, and contemporary political struggles regarding money.

Young People’s Self-Making in Neoliberal Capitalism: Challenges and Opportunities

This paper charts the development of young people’s self-making in neoliberal capitalism, specifying relationships between their self-making and susceptibility to mental health difficulties as they make their way in neoliberal market society. While neoliberal capitalism provides young people with opportunities to pursue and experiment with diverse identities and ways of being in the world, it also structures their self-making opportunities, by which charting selfhood becomes fertile ground for internalizing mental health problems. Our paper argues that the cultural imperative on young people to attain social status and success in the competitive and achievement-oriented forms of life that inhabit neoliberal capitalism demands that they curate and commodify highly desirable forms of selfhood that can never quite be realized. Endlessly failing to satisfy the conditions of selfhood in neoliberal capitalism, exhausted by the injunction to be more than they have already achieved, young people are socialized into increasingly complex and pressurized neoliberal capitalist cultures which challenge their ability to fulfill both their extrinsic desires for status and identity enhancement and their intrinsic needs for relatedness, belongingness, and self-worth. To conclude our paper, we summarize our main arguments and make some recommendations for promoting a more beneficial relationship between young people and the culture of neoliberal capitalism.

How Vital is Nature? Animated Bodies and Agency in Contemporary Capitalism

This paper brings into conversation two ontologies that depart from the anthropocentric norm: new materialism, represented here by the US vitalist philosopher Jane Bennett, and the animated cosmology common among Indigenous peoples, as an example of which I take Braiding Sweetgrass by the Potawatomi bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer. I provide exegeses of both philosophies, with respect in particular to the notion of “animation,” noting that the animated sphere is much more extensive for Bennett than for Kimmerer. I then track Bennett’s shift away from environmental ethics. Finally, I relate differences in philosophy to differences with regard to race and racism, with a detailed discussion of Bennett’s tribute to Walt Whitman, and the genocidal elements within his democratic politics.

Without Rethinking Colonialism and Racialization, a Sustainable Future is Not Possible

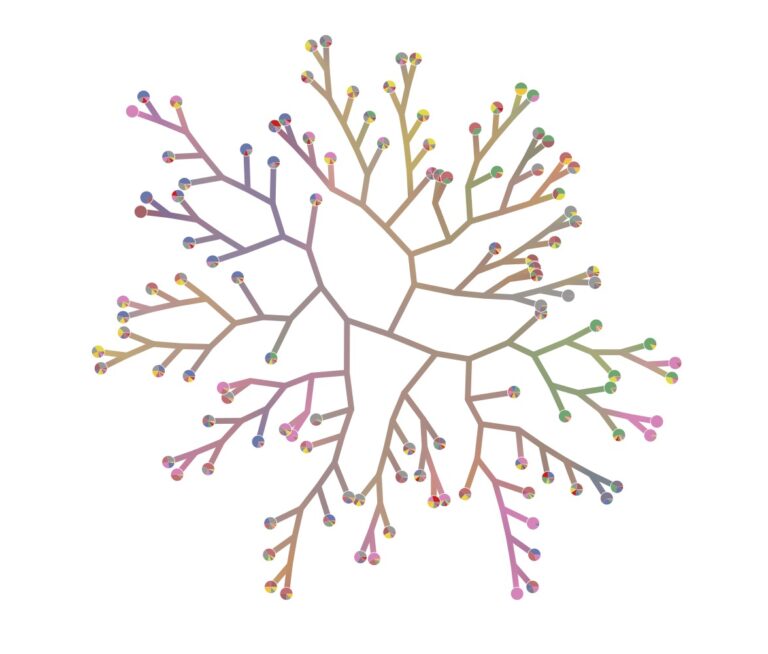

In this article, I talk about the performances of global capitalism, its relation to colonization and racialization, and the ways it hinders the well-being of vulnerable bodies. An understanding of the relation between post-colonialism and post-socialism is crucial to this discussion. I therefore start from a territory that is no longer conceivable today, namely former Eastern Europe and its post-socialism of 1990. I then proceed to discuss the relation of post-socialism to post-colonialism and capitalism. I conceptualize and discuss a diagram that illustrates the relations between the former East, the West, the North, and the South, and in particular, the relation between labour and capital and between capitalism and colonialism across these territories. I suggest that if we are to dismantle imperialism, that is, terminate capitalist colonialism, we need to rethink the racial/colonial divide and the imperial/colonial divide.

Conscious Delirium of a Traveling Body: The Poetics and Politics of a Creative Practice

The question of political economy in the arts offers a way into a creative-critical reflection on the challenges associated with navigating identity labels and living a freelance artist’s life pressured to conform to institutional expectations particularly within the UK’s art scene. This piece is a personal account of a body resisting becoming a symbol, of staying conscious of our socio-political landscape and the ongoing Israeli settler-colonialism. I draw on examples from three of my artworks: the collaborative project From the Lips to the Moon, ongoing nights of longform improvised music and poetry in London; In Observance, a performative research and intervention at the United Nations in Geneva, involving archival documents related to Palestine; and Mishandled Archive, which involves dispersing family photographs and documents in public places, accompanied by daily dances. Through these works, this essay asks: How can historical evidence of imperialism and settler-colonialism be absorbed or resisted within the body? How can we transform loss into movement and togetherness? How late is too late as mounds of rubble and bodies multiply?

Enlightenment by Any Other Name

This essay provides a cursory sketch of the circulation of science as a fetish object in critical theory—particularly by way of an attention to the conceptual popularity of science studies and various permutations of object oriented ontologies. It does so to identify how and under what terms scientific knowledge becomes a necessary site of interdisciplinary collaboration with the humanities, and challenges how these interdisciplinary trafficks disguise forms of epistemic priority ceded to the (hard) scientific method. Identifying in this movement a disavowal of racism in science’s conceptual repertoire and its ongoing claims to objective facticity, the essay criticizes contemporary recourse to science as the newest frontier in critical theoretical scholarship. In contrast to this, the essay poses a much more skeptical approach to the ethics and methods by which such projects develop and critically circulate.