Iyko Day makes a compelling intervention in discussions of race, capital, and settler colonialism. Her book presents a theorization of the abstract economism of Asian racialization by examining how social differentiation functions as a destructive form of abstraction anchored by settler colonial ideologies of romantic anticapitalism. By engaging with capitalism’s abstraction of differentiated gendered and racialized labor in order to create value, Day’s project diverges from scholarship arguing that capitalism profits from labor via the production, rather than the abstraction, of racialized difference (Lowe 1996; Roediger 2008). Her book engages a rich multimedia archive and uses principal historical instances of Asian North American cultural production as theoretical texts to examine key racial policies since the 19th century: Chinese railroad labor in the 1880s, anti-Asian immigration restrictions; internment of Japanese civilians during World War II, and the neoliberalization of immigration policy in the late 1960s.

Keyword: labor

Target Markets and Logistical Management

This paper demonstrates how target marketing provides valuable point-of-sale and point-of-interaction insights, and argues that the labor theory of value is untenable for understanding the conditions of leisure-time surveillance and data aggregation. It then provides a close reading of an Amazon affiliated fulfillment center exposé in order to examine precisely how the information produced during leisure-time surveillance intensifies the exploitation of fulfillment center labor. Target marketing is part of a larger apparatus that aggregates data for the purposes of assigning risk, differentiating prices, and managing supply chains and labor costs.

Mediations around an Alternative Concept of “Work”: Re-imagining the Bodies of Survivors of Trafficking

When I was rescued by the police and put in a shelter home, I felt angry. I did not know any other work. Before, I just had to lend my body and the work got done. I got paid, without having done anything (Poolish jokhon amake uddhar kore Shelter home e dilo, khoob raag hoechhilo.…

Informatic Labor in the Age of Computational Capital

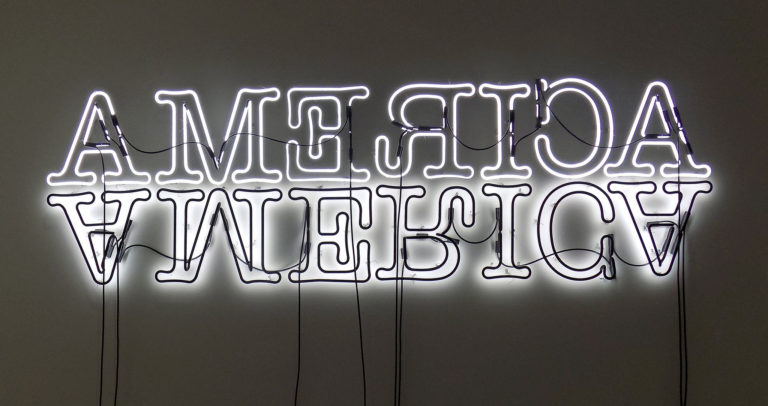

Jonathan Beller expands conversations about the role of the digital and the digital humanities through attention to the mechanisms by which the digital image is instrumental in neoliberal capitalist accumulation and colonialism. Beller argues that the digital image itself exploits the attentive labor of those who see it, organizes profitable patterns of spectatorship, and links communication directly to financial speculation. Through scrutiny of examples that attempt to disrupt the profitable, algorithmically-capitalized flow of data and attention through the interface of the screen, Beller’s article makes a pointed critique of the ways that fascism manifests in and might be combated via digital economies.

“Nothing gold can stay:” Labor, Political Economy, and the Birmingham Legacy of the Culture Industries Debate

Over the course of the last 150 years or so, we can see three distinct phases of the culture industry. More specifically, there have been (at least) three eras marked by different configurations of the relationship between culture, politics, the dominant mode of production and the commodification of culture. Cultural Studies emerged from the second era, whose contours I’ll explore here; and we are now in a liminal phase brought on by the uncertain conflagration between the neoliberalism, convergence culture, and nascent popular uprisings under the banner (and hashtag) #occupyeverywhere. This third phase, or conjuncture, once again reconfigures these relations, making it important to revise the theoretical assumptions and political strategies that were adhered to in an earlier era of “the culture industry.” I will outline the direction I think this points to both in our understanding of the culture industries and in terms of political and theoretical strategy going forward.

The Humanities and the University in Ruin

Mowitt’s essay puts before us in terms of work or, as Mowitt puts it, ‘re: working’ the work of study, scholarship, and research under the contemporary conditions of ‘biopolitical contol’ or neoliberal structural adjustment of the academy. Mowitt warns against reducing the issue of study to complaints of poor pay and poor working conditions and therefore holds the issue of the labor of study on a fine line between the refusal of the work of study altogether and the insistence on simply enjoying the study that we are required to do or paid to do. Mowitt is not denying the poor conditions under which so many of us work for insufficient pay in and outside the University; he rather is warning us about moving too quickly off the fine line between refusal and enjoyment of the required or paid work of study. He is arguing instead for the value of study as a labor of the negative. Mowitt then takes some elegant last moves to turn this return to the labor of the negative into the work of affirmation, thought affirming itself; he thereby moves beyond the dialectic and the Euro-centric Hegelian tradition of progress to affirm instead the immanent unfolding of mindfulness or thoughtfulness, an unfolding of an affective labor that bears within it the in-excess of measure, the yet-incalculable excess of the current calculability of value. This makes the re: working of study not merely a matter of the human or the humanities but of the technical/human medium we fast are becoming, and which we are coming to know we always have been, as has the University.

Response to “The Humanities and the University in Ruin”

In his response to Mowitt, Morgan Adamson sharply reminds us that working conditions and remuneration for work, not to mention layoffs, hiring freezes and slashing of benefits, certainly are pressing concerns. Offering a quick survey of some of the horrid details of the work expected of research assistants in science labs, Adamson also softens the distinction implied in Mowitt’s focus on the humanities as against the sciences.

Response to “The Humanities and the University in Ruin”

Adam Sitze addresses the technological transformation of the academy, emphasized critically by Mowitt, which have put us beyond the troubles of discipline or disciplinarity to something more abstract and technical.