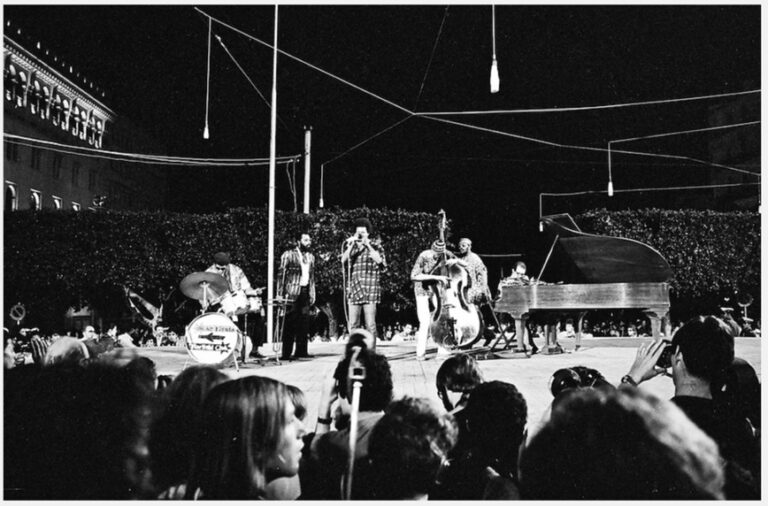

This assembled interview centers both Elaine Mokhtefi and Le premier festival culturel panafricain d’Alger 1969 (PANAF), a festival which she organized and attended as a part of the Algerian Ministry of Information, noting it as an exemplary instance of the power of performance at the nexus of political ideology, activist history, and the subsequent nostalgia for that era of liberation. It is equally an attempt to overcome a distant relationship to each, reflecting on the potential of oral histories to open up new pathways through the past. This history—of entangled international relations negotiated under the guise of a festive performance, a complicated trajectory of global politics which culminated in a remarkable event of celebration and solidarity—remains understudied, a footnote to more “political” concerns of Third World agendas, decolonial reorderings, and capitalist critiques. Yet through Mokhtefi’s testimony, interwoven with searching tendrils of archival detail, we can see that this festival was not a superficial exaltation in extravagance, but a pivotal moment in foreign affairs. More importantly, through her personal history, we can trace the central role that women played in these politics, if often unacknowledged. Edited in 2020, it also counters the pejorative label of non-essential labor applied to most cultural activities during the contemporary pandemic response to COVID-19.

Issues

Introduction: Cripistemologies of Crisis: Emergent Knowledges for the Present

The increasing recognition of critical disability studies as a generative body of work across disciplines is inseparable from a collective need to make sense of ongoing moments of socio-political crisis, emergency, and exceptionality. Theorizations of crip time emergent from lived experiences of disability are critical to the ongoing work of understanding and surviving a chronically debilitating socio-political context. Our current political moment seems to protract states of crisis to such a degree that the very notions of emergency and crisis shift under the weight of their simultaneous seeming banality and urgent ubiquity. “Cripistemologies of Crisis: Emergent Knowledges for the Present” contends that epistemologies of chronicity, illness, and trauma offer indispensable lenses through which to rethink—and care for—our collective present. The essays within “Cripistemologies of Crisis” reframe our understandings of both social and personal crisis, and explore how crisis and emergency shape the experiences and knowledges of our bodyminds in time and space. The authors collectively offer an epistemological toolkit to theorize and survive everyday states of trauma, madness, and illness as the lived impacts of such quotidian and ongoing violence. “Cripistemologies of Crisis” asks, then, what crip futures can be conjured through a centering of experiential, collective, and speculative ways of knowing with/in/through crisis.

When Silence Said Everything: Reconceptualizing Trauma through Critical Disability Studies

Reading X González’s, March 24, 2018, “March For Our Lives” speech—their words and silences—as an entry point into what I term a crip theory of trauma, this essay argues that the dominant narratives about and around Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) say more about the compulsivity of the “proper” citizen subject than they do the actual embodied experience and debilitation of trauma itself. The text reconceptualizes trauma narratives, like González’s, through critical disability studies to argue that certain cripistemologies—or crip ways of knowing—trauma arise that are not otherwise available or readily accessible. Most notably, by rejecting dominant pathologizing forces and embracing crip ways of knowing, this analysis brings forth a new working definition of trauma, as an embodied, affective structure. These ways of knowing offer crucial insights for efforts to grapple with the ongoing forms of trauma enacted and perpetuated across the globe, and are particularly urgent against a political and cultural landscape that, as my reading of González’s speech makes clear, in many ways refuses to hear, see, and learn from the knowledge that trauma produces.

Solidarity in Falling Apart: Toward a Crip, Collectivist, and Justice-Seeking Theory of Feminine Fracture

In this essay, I reconceptualize feminized trauma by utilizing a queer crip feminist disability justice framework. This reconceptualizing allows for an intervention in both historical psychoanalytic and contemporary biomedical framings of the experience of gendered and sexual violence, pursuant or sequelic trauma, and associated symptoms. Both historical and contemporary psycho-logics too often imagine gendered and sexual violence as abnormal or exceptional events (e.g., “stranger rape”) which can be treated and cured individually, thus delimiting them within a white, wealthy or middle-class, cis- and hetero-feminine register. As a corrective, within the framework of everyday emergencies, insidious traumas, and cripistemologies of crisis, I position feminine fracturing and falling apart as chronic, and consider abolitionist strategies for survival, care, and solidarity beyond traditional medical frameworks for recovery. This further provides a way to understand dissociation or rather dissociative-adjacent symptomology as real, legitimate, and painful, yet also as sociopolitical products experienced differently across diverse populations—and as mundane, banal, and even expected for some. Here, feminine fracturing is symptom, method, and potential avenue for change or liberation. What does “recovery” look like when feminized trauma is endemic to the point of being so normalized and unexceptional as to be a thoroughly unremarkable part of our everyday cultural backdrop? How is this exacerbated when we examine the experiences of trans women, poor women, and immigrant and BIPOC women and femmes? I posit that there is promise in embracing a fracturing, in falling apart—as antidote to the normative and neoliberal logic of keeping it together.

Crip Collectivity Beyond Neoliberalism in Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower

The importance of Octavia Butler’s 1993 novel Parable of the Sower continues to crystalize, as Butler’s prescient imagining of urban California torn apart by neoliberal divestment comes to fruition. Following in the space opened up by Black feminist scholarship on Butler, the present essay examines her relevance beyond literary and cultural studies. I argue that Parable is a Black feminist crip theorization of political economy that diagnoses the disabling conditions of precarity under neoliberalism and also prescribes collectivity for crip and mad survival. Neoliberalism describes a global stage of advanced capitalism wherein governments are both incentivized and disciplined into enforcing economic policies that include privatization, deregulation, and market liberalization. As Jodi Melamed defines it, neoliberalism requires a certain kind of political governance, that puts the interests of business over the well-being of people (2011). Neoliberal governance engenders what I call “disabling contradictions,” yet the blame for conditions of precarity is deflected onto bodyminds themselves. In Parable of the Sower, Butler theorizes these disabling contradictions of neoliberal governance under advanced capitalism, drawing into focus the political economic systems that cause suffering. Parable also depicts strategies for crip and mad survival that are made possible through the conscious creation of community and networks of solidarity that counter the neoliberal state’s devaluation of bodyminds. Gathering to read and discuss the novel, rather than a distraction from the crises, furthers the emergence of crip and mad collectivities. As such, it is an urgent and timely practice for building futures for crip and mad people.

Review of Gestures of Concern by Chris Ingraham (Duke University Press)

Chris Ingraham’s Gestures of Concern considers how affective communities can be built by and through concerned gestures. His analysis of the political power of a range of these gestures—from the small tokens of get-well cards to the political protests against shuttered public resources such as libraries—emphasizes their affect as much as their action. Ingraham pays attention to the background of concerned gestures that are political, aesthetic, and community-based, and his analysis of their efficacy and their impact draws readers to consider different kinds of critical resistance in the face of growing social disparities.

Review of Robo Sapiens Japanicus: Robots, Gender, Family, and the Japanese Nation by Jennifer Robertson (University of California Press)

Jennifer Robertson’s Robo Sapiens Japanicus: Robots, Gender, Family, and the Japanese Nation assesses the robot phenomenon in Japan within the last decade. Offering sustained critiques on contemporary techno-fix narratives, Robertson reveals how humanoid robots are designed and deployed to reify conservative values under the guise of technological advancements. Robertson’s impressive ethnographic project weaves together robots of science fact and fiction, leaving readers to interrogate how humanoids, androids, gynoids, and cyborgs both challenge and reify existing social structures across the globe.

Review of Open World Empire: Race, Erotics, and the Global Rise of Video Games by Christopher B. Patterson (New York University Press)

In Open World Empire: Race, Erotics, and the Global Rise of Video Games, Christopher B. Patterson critically analyzes video games through the methodological framework of erotics. In doing so, he provides astute insights into the ways in which video games can work to challenge essentialized narratives and constructions of race while also fostering greater awareness and understanding of one’s own place within the larger geopolitical systems of capitalism and empire. Through understanding video gamers as not simply passive receptors of ideology, but rather as active participants in the gameplay experience, he contends that video games create pleasure and other forms of affective engagement through erotic play. Through this erotic play, Patterson argues that “games enact playful protests against the power, identity, and order of information technology” (7).

Review of Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man by Joshua Bennett (Harvard University Press)

Reading a robust archive of twentieth and twenty-first century African-American literature, Joshua Bennett’s Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man lays the foundations for rethinking kinship and relation between humans and animals.

Review of Disruptive Situations: Fractal Orientalism and Queer Strategies in Beirut by Ghassan Moussawi (Temple University Press)

Ghassan Moussawi’s Disruptive Situations challenges the exceptionalist representations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans (LGBT) experiences in Beirut through a focus on the everyday queer strategies and tactics. Moussawi analyzes the everyday practices of LGBT interlocutors navigating al-wad’ (the situation), a term that refers to the normative order of disruptions, precarity, and instability that permeate daily life across contemporary Beirut. Al-wad’ simultaneously features as a historical condition of perpetual instability bearing on daily life in Beirut, as well as a lens to analyze the practices of everyday life for Moussawi’s LGBT interlocutors. Moussawi’s inductive ethnographic approach charts the strategic use of identities, visibility, and “bubbles” or sources of solace in order to challenge exceptionalist representations of Beirut and LGBT experiences in the city. Moussawi critiques these reductive representations as “fractal orientalism”, a reductive representation that embeds hierarchies and exclusion through geographic associations, such as in fashioning Beirut as the “Paris of the Middle East”. Beirut becomes charming and “cosmopolitan” in a way that is similar to, but not quite, the same as Paris. Moussawi’s focus on queer daily practices against the backdrop of al-wad’ shows the limitations of these reductive representations in an effort to reimagine queerness, subjectivity, and politics.

Review of Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern California Iranian Pop Music by Farzaneh Hemmasi (Duke Press)

Tehrangeles Dreaming is the first book about the Tehrangeles music industry, that is, the Iranian diaspora music industry brought to life by the expatriate Iranian artists and music producers who settled in Los Angeles and Southern California after the 1979 Iranian revolution. Farzaneh Hemmasi uses an ethnographic approach in combination with an analysis of diaspora media discourse in order to “examine expatriate imaginations of influence on, and intimacy with, their global Iranian audiences” (26). At its core, the book deals with the imagining and reimagining of Iranian identity by the artistic community that creates music and media content for Iranians in Iran and across the world.

Review of The Anti-Capitalist Chronicles by David Harvey (Pluto Press)

The Anti-Capitalist Chronicles is a collection of accessible, loosely connected essays by influential Marxist geographer David Harvey. Based on episodes of Harvey’s podcast of the same name, the book tackles topics related to the contemporary and historical crises of global capitalism. In nineteen brief, topical chapters, Harvey appropriates and reimagines Marxian categories and anti-capitalist frameworks of various kinds in order to report on the changing shape of global capitalism considered as a historically distinct social formation, the internal logics and contradictions which govern capital’s movements in the world, and the obstacles to be overcome by socialist politics.

Review of Digitize and Punish: Racial Criminalization in the Digital Age by Brian Jefferson (University of Minnesota Press)

In Digitize and Punish, Brian Jefferson argues that the US policing and incarceration infrastructure is increasingly marked by new forms of racialized digital criminalization. Examining the incorporation of digital technologies into the criminal justice apparatus, Jefferson shows the central role that digital technology and data science has had in reinforcing racial surveillance practices since the War on Drugs and Crime began more than four decades ago. Jefferson’s timely new book traces the merging of carcerality and technology in Chicago and New York City, unveiling forms of digital racial management that have remained largely obscured from the public.

Introduction: Cultural Constructions of Race and Racism in the Middle East and North Africa / Southwest Asia and North Africa

In recent years, scholars in the fields of cultural studies, American studies, history, ethnic studies, and Middle East area studies have approached questions of race and racism in this geographic region with renewed critical vigor. Recent work deconstructing anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia in the Americas and Europe has put these patterns of discrimination into intersectional conversation with anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism. New historical efforts have drawn attention to the legacies of slavery in the Ottoman, Persian, and Arab Empires, working to understand how forms of racialization and racial hierarchization predated and were exacerbated by the arrival of European imperial forces. At the same time, activists in the region draw attention to prevailing racism against migrant laborers, marginalized indigenous populations, and others as the afterlives of colonialism, war, austerity, and revolution carry on. Together, this academic and activist work asks for attention by leaders, community members, and scholars of this region to the particularities of racecraft in the region: How are “Blackness” and “whiteness” constructed in the Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, and Turkish speaking worlds? What are the obstacles to discussing and identifying race particular to the histories of this region, its peoples, and its histories? This forum uses close readings of popular culture and political discourse across the Middle East and North Africa / Southwest Asia and North Africa (MENA/SWANA) in pursuit of these questions and others.

The Myths of Haji Firuz: The Racist Contours of the Iranian Minstrel

Every year, around the arrival of the Spring equinox, Iranians in Iran and in diaspora will recognize a minstrel named Haji Firuz with his Nowruz jingle. The inclusion of Haji Firuz during Nowruz festivities has been questioned and challenged for decades; where some will point out his connections to anti-Blackness, others will defend Haji Firuz, arguing that his face is only covered in soot from fires also associated with the holiday. This article contextualizes these arguments as a part of a larger discourse of denying racism in Iran and, more poignantly, erasing Iran’s history of slavery altogether. This article addresses the consequences and pitfalls of defending Haji Firuz’s blackface performance, and its implications for the broader Iranian community.