In much proto-nationalist discourse and academic and historical work, marronage has come to represent an open receptacle of competing narratives and desires in the history of slavery, revolt, and Blackness. Paying attention to the ways marronage is portrayed across the different nations and territories of the Caribbean reveals grand narratives of heroism, the formerly enslaved outsmarting and outlasting planters and colonial officers in the hills and mountains of the West Indies and the swamplands of the US South. Through these narratives, this article argues, the maroons are mythologized both as figures of resistance against the racial terror of slavery and as the founding fathers of the post-Abolition, post-Independence Caribbean nation-state. These heroic yet limited depictions of marronage, though important in showing the ways the maroons were able to unsettle the plantocracy, fail to reckon with the impossibility of redress in the afterlives of slavery and the limits of sovereignty in the wake of the non-event of Emancipation. Marronage offers neither a clean break from slavery nor an easy path beyond, yet the proto-nationalist accounts of its praxis that I explore here insist on turning the incapacity of the enslaved into the capacity—to resist, to survive—of the heroic maroon. Through its calculated erasure of slavery, the marronage produced in these narratives generates its own set of aporias, pointing us in the direction of freedom but reminding us, at the same time, of its impossibility. What is at stake in this article is not an exploration of the future of marronage but the exploration of its past and its supposed break from slavery, as well as an interrogation of the ideals of Black resistance and Caribbean sovereignty and freedom that the heroic maroon is tasked with representing.

Keyword: Blackness

Everyday Black Futurity in Popular Culture

Black popular culture draws on everyday Black experiences to create ideas of futurity. There are well known examples of Afrofuturism, such as the Black Panther films, as well as the music of George Clinton, Sun Ra, Janelle Monáe, and Erykah Badu, which offer profound versions of Black futures. In addition to these essential examples, some artists are not always explicitly named as such and incorporate robust conceptions of futurity and speculation into their work. This article examines the performances of Missy Elliott, Megan Thee Stallion, and Cedric the Entertainer. It argues that through their embodied performance practices that cite Black life, they create persuasive critiques of the present and move forward ideas about the future. In addition to using futuristic settings and themes, their embodiments work to put forth compelling ideas of speculation. These artists employ notions of the posthuman, a speculative figure that interrogates the category of the human through embodied gestures, dances, and other movement styles. The examined performances challenge notions of respectability established through white norms and neoliberal disciplinary mechanisms that police and harm Black bodies and render them outside of humanness. Specifically, Missy, Cedric, and Megan’s performances are rooted in concepts like ghetto, ratchet, and hood, which push back against US society’s notions of the human as defined through the respectable laboring body that is also read through the standard of whiteness. The twin dynamic of the human and posthuman provide critiques of the historic and layered expansiveness of anti-blackness while also centering Black people’s joy, pleasure, desire, and freedom. As such, these performances proffer notions of the present and future, the human and the posthuman. The force and effectiveness of these artists’ performances reside in how they draw from the everyday ways Black people articulate ideas of radical futurity.

Review of Translating Blackness: Latinx Colonialities in Global Perspective by Lorgia García Peña (Duke University Press)

In Translating Blackness, Lorgia García Peña offers a transnational conceptualization of Black Latinidad. Framing Black Latinidad as an epistemology, García Peña traces its historical and contemporary formations through the lives and the work of historical Black Latinx intellectuals as well as contemporary Black and Black Latinx individuals in the Carribean, Italy, and the United States. García Peña approaches Black Latinidad as produced through vaivén—coming and going across physical and symbolic borders of nation-state and migrant-citizen categories that characterizes the sociological position of Black Latinx individuals.

Review of The Long Emancipation: Moving Toward Freedom by Rinaldo Walcott (Duke University Press)

In The Long Emancipation: Moving Toward Freedom, Rinaldo Walcott argues, through the use of short essays, that the Black experience can be understood through the lens of the constant struggle for emancipation. For Walcott, true freedom for Black people was never attained with emancipation and in fact, emancipation is still an ongoing process. Each chapter interrogates an aspect of Black life and death that according to Walcott create the space for Black freedom to exist.

Review of Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures by André Brock, Jr. (New York University Press)

In Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures, interdisciplinary scholar André Brock, Jr. offers a timely and powerful examination of Blackness in the digital age. The book centers Black technology use from Black perspectives and investigates the online distribution of Black discourses. In six exploratory chapters, Brock reconceptualizes Black technoculture in a way that corrects deficit models of Black digital practice.

Opposing A Spectacle of Blackness: Arap Baci, Baci Kalfa, Dadi, and the Invention of African Presence in Turkey

The imaging of Africans in Turkey is indicative of the extant register of cultural understanding in the Turkish popular imagination regarding the imaginability, knowability, and understandability of Black form represented. In Turkish popular culture, the figures of the arap baci, baci kalfa, and dadi index this register. This essay takes the representation of Africans on Turkish popular television through the combined usage of blackface-like and drag-like techniques to configure the figures of the arap baci, baci kalfa, and dadi and juxtaposes it against the material ways Turks of African descent have found to figure themselves within the public sphere. This juxtaposition demonstrates how Blackness and Black form are not perennial processes but rather constructed measures that come into relief.

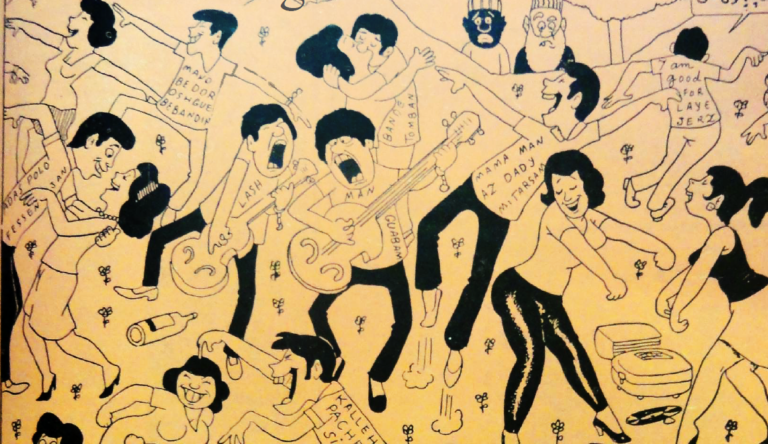

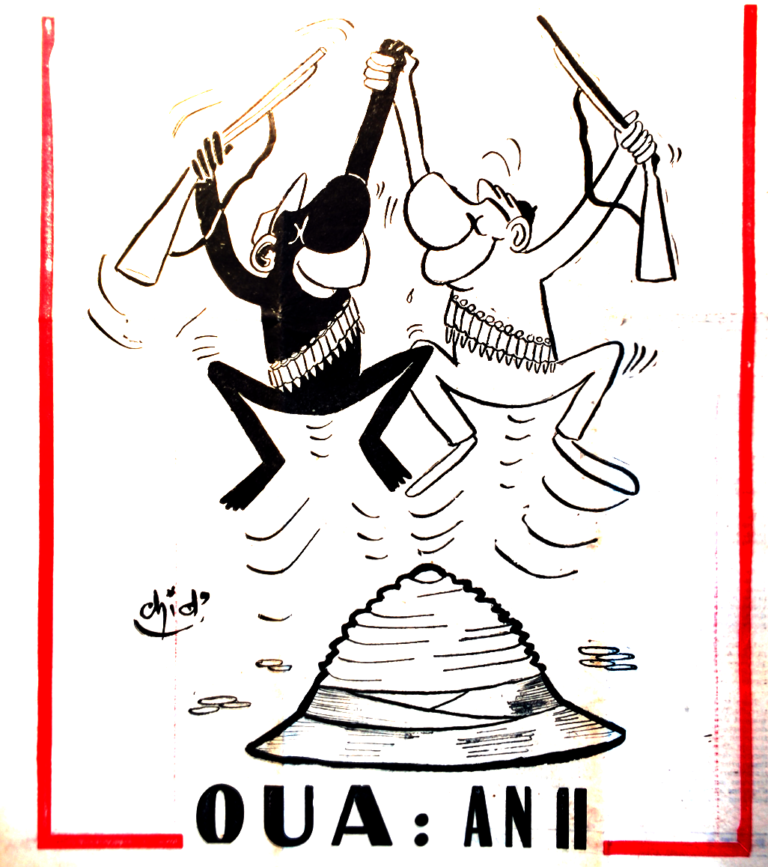

Thaumaturgic, Cartoon Blackface

This essay explores how a particular medium—the comic—exposes the limitations of conventional narratives about sīyāh bāzī (Persian blackface) and hājī fīrūz (a famous blackface figure). Many commentators disavow the racial connotations of sīyāh bāzī and hājī fīrūz, concocting pseudo-historical genealogies that link the improvisatory tradition and figure to pre-Islamic practices; commentators thus repress the tradition’s obvious resonances with the history of African enslavement in Iran. Through a close reading of a comic strip from a 1960s Persian periodical, I argue that historicism is an inadequate framework for adjudicating sīyāh bāzī’s racial or “nonracial” character. Instead, I suggest that cartoon Blackness is always already racial, since the comic form depends upon a process of simplification that is at the heart of racialization.

“Incommensurate Ontologies”? Anti-Black Racism and the Question of Islam in French Algeria

In recent years, scholars and activists in France and the United States have questioned whether discrimination against Muslims constitutes a form of racism. In France, some on the left have claimed that religion is a category of belief and therefore should remain separate from discrimination based on skin color or other physical characteristics. In the United States, Afropessimist approaches insist on the specificity of anti-Black racism, rooted in the historical difference between the native and slave. This article, by contrast, argues that race and religion should be studied relationally and highlights how being Muslim exceeded the frame of personal conviction in colonial Algeria, where religious identity was the basis of a political and economic project that were constructed in their wake. The works of Frantz Fanon are particularly instructive in this regard, as he insisted on viewing Blackness as fundamentally relational and also drew on his analysis of anti-Black racism in mainland France to understand the dynamics of settler colonialism in Algeria. The porous line between religious and racial categories also sheds light on discussions of sectarianism in the Middle East more broadly, as colonial regimes irrevocably shaped the contours of the nation-state that were constructed in their wake. Postcolonial sectarianism inherited the intimate relationship between race and religion constructed by empire.

What is Whiteness in North Africa?

This entry sketches a matrix for conceptualizing race in/ and North Africa that takes Arabness, indigeneity, Islam, the Sahara, and slavery as orienting keywords. It suggests an approach to a geopolitically-grounded whiteness as social currency and aspiration that is both based in specific regional economic history and also reaches outward toward globally-circulating formations of racial hierarchy. Acknowledging the distinct legal, colonial, and state histories under and through which racialization has proceeded in North and Saharan Africa since the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, this entry aims to draw out the ethical imaginaries through which bodies have been marked and categorized in this region. These ethical imaginaries have operated through their attendant languages, memories, and performances to enable racisms and colorisms with violent and enduring material consequences. Under the headings “Racialized Enslavement,” “Whiteness and Arabness,” “Race and the Sahara,” and “Race in North African Popular Culture,” I offer brief introductions to these discursive formations, histories, and conceptual intersections and offer suggested readings for each.

Political Blackness, British Cinema, and the Queer Politics of Memory

This essay queries “political Blackness” as a coalitional antiracist politics in England in the 1970s and 1980s. Contemporary debates on the relevance of political Blackness in contemporary British race politics often forget significant critiques of the concept articulated by feminist and queer scholars, activists and cultural producers. Through close readings of Isaac Julien and Maureen Blackwood’s The Passion of Remembrance and Hanif Kureishi’s Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, this essay examines cinematic engagements with political Blackness by foregrounding the gender and sexual fault lines through which queers and feminists articulated relational solidarities attentive to difference.

Review of Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia by Sabrina Strings (New York University Press)

In Fearing the Black Body, Sabrina Strings argues that the origins of present day fat phobia stem from moral and scientific shifts of the Enlightenment period. Affected by a history of racial slavery in America and other parts of the world, the religious, medical, philosophical, and aesthetic opinions of elite white men shaped how the white woman’s body became representative of nationhood through its ascriptions as morally right in its svelte figure. The black woman’s body, ostensibly the complete opposite (i.e., obese and worthy of denigration), consequently became the basis for the favored white woman’s essentialized attributes.

Review of Sensual Excess: Queer Femininity and Brown Jouissance by Amber Jamilla Musser (NYU Press)

In Sensual Excess, Amber Jamilla Musser develops an epistemological project that calls into question modes of producing knowledge around black and brown bodies, especially in relationship to femininity and queerness. In doing so, she interrogates the kind of racialized understandings of femininity produced by what Hortense Spillers has called “pornotroping” in order to draw a contrast to something Musser calls “brown jouissance.” She is looking for those places where fleshly experience exceeds the ideological constraints of the pornotropic image, developing an epistemology based not on the visual, but on the affective experiences of the flesh. In doing so she analyzes Lyle Ashton Harris’s Billie #21 (2002), Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1979), Kara Walker’s A Subtlety (2014), Mickalene Thomas’s Origin of the Universe 1 (2012), Cheryl Dunye’s Mommy is Coming (2012), Amber Hawk Swanson and Sandra Ibarra’s Untitled Fucking (2013), Carrie Mae Weems’s From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995–1996), Nao Bustamantes’s Neapolitan (2003), and Maureen Catabagan’s Crush (2010–2012).

Review of Political Blackness in Multiracial Britain by Mohan Ambikaipaker (University of Pennsylvania Press)

Mohan Ambikaipaker’s “Political Blackness in Multiracial Britain” is distinctive both for its setting and for its personal engagement. Ambikaipaker practiced “activist anthropology” by carrying out “observant participation” as a caseworker for the Newham Monitoring Project, a community activism organization, over the course of two years. The book alternates between anecdotal accounts of racism and the author’s theoretical and historical framing of those accounts. Ambikaipaker’s writing is compelling, his theoretical grounding is thorough, his empathy is apparent, and the fieldwork underpinning it is considerable and consequential.

Review of In the Wake: On Blackness and Being by Christina Sharpe (Duke University Press)

Christina Sharpe’s “In the Wake: On Blackness and Being” addresses issues of citizenship, racial violence, and black mortality, meshing her personal experiences surrounding death and “the wake” with a sharp critique of cultural structures, as well as a reimagining of slavery, funeral, and death metaphors. In the wake of so many “ongoing state-sanctioned legal and extralegal murders of Black people,” Sharpe’s argument that black death is a foundational aspect of American citizenship encourages readers to acknowledge the antiblackness embedded in the past, present, and future of American (and by extension, Transatlantic) democracy (7). With the continued and encouraged proliferation of black death in the global diaspora, Sharpe’s study will, hopefully, usher in more woke scholarship that questions pervasive antiblackness.

Review of Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction by André M. Carrington (University of Minnesota Press)

André Carrington’s ‘Speculative Blackness’ is a novel approach to the consumption of race representation in media. Carrington explores how Blackness is manufactured, consumed, and transformed through the speculative fiction genre across multiple 20th and 21st century mediums. Traditional media of comic books and television shows reveal the marginalized status of Black figures however, these media do not exist in a vacuum. The consumption of speculative fiction is a transformative process for the original content, which consequentially produces amateur media due to a long-established history of fan interaction. Black representation is characterized as the exception, not the rule, in traditional production, but fan consumption reconfigures these notions. Ultimately, Carrington’s work is an innovative dialogue regarding a genre that creates worlds speculating on what could be. Speculative fiction breaks down preexisting notions of our reality and creates worlds with entirely new expectations and interactions. With the creative liberty of the genre, Carrington casts Black representation as a consumed media but also an imaginative effort.