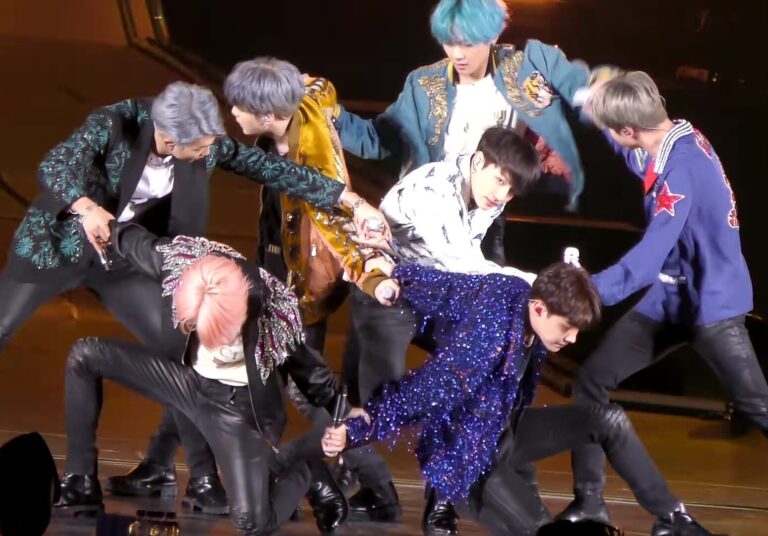

This article makes the case that the discourse around K-pop supergroup BTS and their fans—known as ARMY—marks an intersection between techno-Orientalism, the abstraction and demonization of Asian labor, and Korea in the US imperial imaginary. BTS exemplifies what I suggest is a contemporary form of Asian racialization that emphasizes the Asian figure as embodying a series of seeming contradictions between the synthetic/mechanistic and the undeveloped/primordial. BTS reveals the ways that these threads of racialization do not contradict but rather complement each other, explaining how narratives marveling at the group’s technical proficiency/synchronicity/productivity can exist side by side with suggestions that their musical output is the result of a labor that is denigrated because it is perceived as being mechanized, abstract, and devoid of the qualities of artistry and creativity exclusively associated with Western modernity.

Keyword: racialization

Review of Media and the Affective Life of Slavery by Allison Page (University of Minnesota Press)

In Media and the Affective Life of Slavery, Allison Page interrogates how media culture from the 1960s to the present has mobilized the legacy of slavery for affective governance, or “the production and management of affect and emotion to align with governing rationalities” (6). Throughout the book, Page’s analysis succeeds in providing a rich mapping of the converging interests of state actors, media producers, educational organizations, and other stakeholders as they narrate their own desire to manage emotions in the wake of the civil rights movement and to maintain white supremacist order.

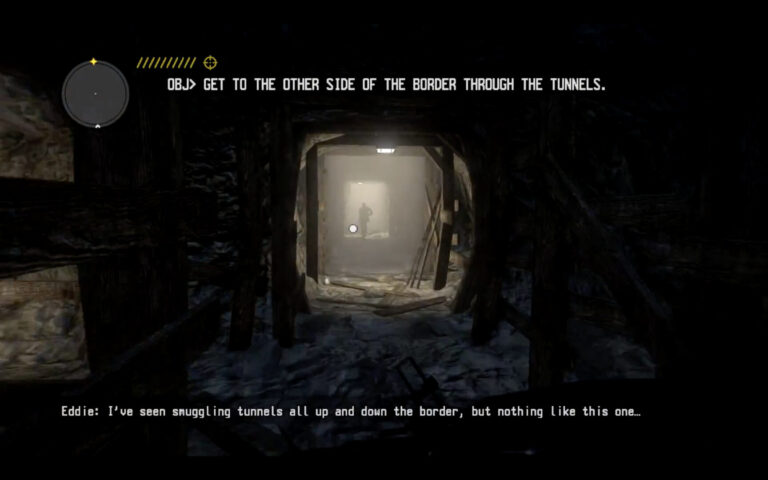

First-Person Shooters, Tunnel Warfare, and the Racial Infrastructures of the US–Mexico Border

Digital networked media actively participate in the nation-state’s and tech entrepreneurs’ efforts to imagine and manage the borderlands. These media facilitate virtual forms of thinking about the border both by offering popular reference points for the new technology being developed (e.g. Google Maps, Pokémon Go, Call of Duty) and by providing the actual tools through which these ideas can become actionable. This article analyzes one such reference point within the first-person shooter (FPS) console game Call of Juarez: The Cartel (Ubisoft, 2011). Like other border-themed video games, The Cartel borrows on colonial tropes and ideologies by creating playable narratives that invoke the untamable frontier and position racialized subjects as Other. Through its virtual modes of representation and interaction, the game encodes the racialization processes that continue to shape popular imaginings of the border. While its digital aesthetics animate a dynamic space of possibility, the logic of the first-person shooter reins in the expansiveness of animated space by restricting it to an interactive experience of tunnel warfare, an ideological orientation to the border underground that channels the players’ purposive motion into a space of direct confrontation and racial violence. Analyzing the narrative and procedural work of this ostensibly reactionary video game demonstrates how border infrastructures structure and shape specific forms of racial and colonial violence.

Within and Against Racial Segregation: Notes from Italy’s Encampment Archipelago

The pandemic brought migrant farm workers into the limelight once again, as has happened repeatedly in the last three decades, in Italy as in many other parts of the world. Here I examine how intersecting and sometimes conflicting discourses and interventions, that have this biopolitically conceived population as their object, decide upon these subjects’ worthiness of attention, care, and sympathy through criminalizing, victimizing, and humanitarian registers. I reflect on some of the affective dynamics that sustain both the governmental operations through which these populations were (sought to be) managed and reactions against them from a situated perspective, as an accomplice to many of the forms of struggle in which migrant farm workers have engaged in the last decade in Italy. The stage for many such occurrences is what I have elsewhere defined as the “encampment archipelago” that many such workers, and particularly those who migrate from across West Africa, inhabit—labor or asylum-seeker camps, but also slums or isolated, derelict buildings, and various hybrid, in-between spaces among which people circulate.

Introduction: Cultural Constructions of Race and Racism in the Middle East and North Africa / Southwest Asia and North Africa

In recent years, scholars in the fields of cultural studies, American studies, history, ethnic studies, and Middle East area studies have approached questions of race and racism in this geographic region with renewed critical vigor. Recent work deconstructing anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia in the Americas and Europe has put these patterns of discrimination into intersectional conversation with anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism. New historical efforts have drawn attention to the legacies of slavery in the Ottoman, Persian, and Arab Empires, working to understand how forms of racialization and racial hierarchization predated and were exacerbated by the arrival of European imperial forces. At the same time, activists in the region draw attention to prevailing racism against migrant laborers, marginalized indigenous populations, and others as the afterlives of colonialism, war, austerity, and revolution carry on. Together, this academic and activist work asks for attention by leaders, community members, and scholars of this region to the particularities of racecraft in the region: How are “Blackness” and “whiteness” constructed in the Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, and Turkish speaking worlds? What are the obstacles to discussing and identifying race particular to the histories of this region, its peoples, and its histories? This forum uses close readings of popular culture and political discourse across the Middle East and North Africa / Southwest Asia and North Africa (MENA/SWANA) in pursuit of these questions and others.

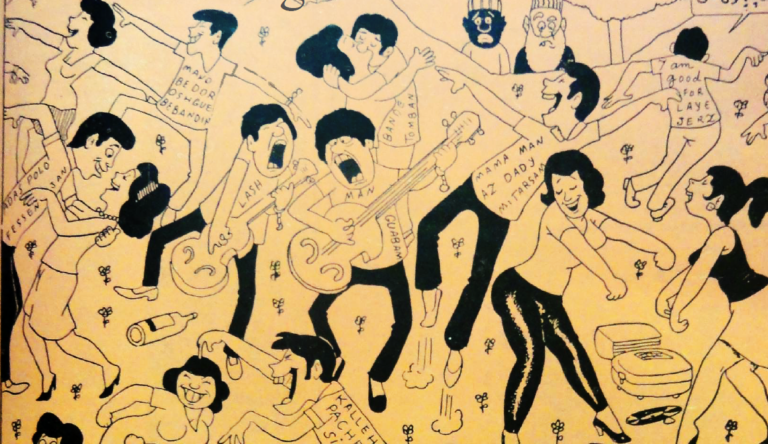

Thaumaturgic, Cartoon Blackface

This essay explores how a particular medium—the comic—exposes the limitations of conventional narratives about sīyāh bāzī (Persian blackface) and hājī fīrūz (a famous blackface figure). Many commentators disavow the racial connotations of sīyāh bāzī and hājī fīrūz, concocting pseudo-historical genealogies that link the improvisatory tradition and figure to pre-Islamic practices; commentators thus repress the tradition’s obvious resonances with the history of African enslavement in Iran. Through a close reading of a comic strip from a 1960s Persian periodical, I argue that historicism is an inadequate framework for adjudicating sīyāh bāzī’s racial or “nonracial” character. Instead, I suggest that cartoon Blackness is always already racial, since the comic form depends upon a process of simplification that is at the heart of racialization.