This essay negotiates the critical tension between race as an analytic and social construct by examining how race becomes socialized in and through the production and presentation of Arab culture in two ethnographic case studies: how Syrian musicians negotiate musical multiculturalism as they integrate into German society and how independent musicians in Egypt navigate the racialized entanglements of national and international security logics that privilege Western foreigners. Both these case studies center the “foreigner” subject as one who embodies proximity to white power and delimits the boundaries of such power. We argue that the category of foreigner is thus a racialized construct that not only complicates the Black–white binary of race relations but strategically evades explicit discourses and practices of racecraft that are violent, discriminatory, and exclusionary. By provincializing critical race theory through the particularities of Arab lived experience, we illustrate how local social categories are entangled with historic legacies of empire and contemporary global logics of racialized difference while remaining sensitive to how conceptions of difference exceed Euro-American categories of race. Our work therefore directs attention towards alternative enactments of racialization within the Global South.

Issues

On Blackness and the Nation in Arabic Hip Hop: Case Studies from Lebanon and Libya

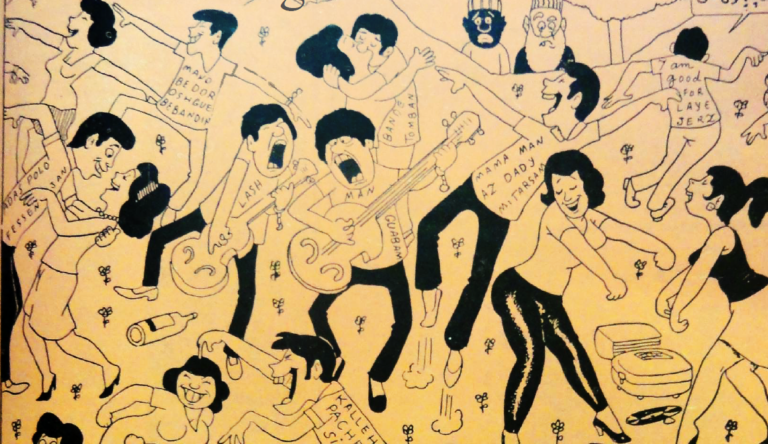

In this contribution, Chris Nickell and Adam Benkato think together about the mobilization of Blackness in Arabic hip hop from two different contexts: a rap battle in Beirut, Lebanon and music videos from Benghazi, Libya. In both, hip hop artists confront Blackness with the nation through the Afro-diasporic medium of hip hop. Although the examples we consider here participate, in several ways, in hip hop’s larger generic functions as a globalized Black medium of resistance, they also bolster pre-existing discourses of race and racism, anti-Blackness in particular. We argue that this seeming contradiction—instances of anti-Blackness appearing in an iteration of a Black expressive form—is in fact a feature, not a bug, of the flexible way the genre works. We have paired these two examples, which we describe and analyze individually given their differing social contexts as well as our differing research focuses, in order to glimpse the discursive level at which racecraft functions.

Opposing A Spectacle of Blackness: Arap Baci, Baci Kalfa, Dadi, and the Invention of African Presence in Turkey

The imaging of Africans in Turkey is indicative of the extant register of cultural understanding in the Turkish popular imagination regarding the imaginability, knowability, and understandability of Black form represented. In Turkish popular culture, the figures of the arap baci, baci kalfa, and dadi index this register. This essay takes the representation of Africans on Turkish popular television through the combined usage of blackface-like and drag-like techniques to configure the figures of the arap baci, baci kalfa, and dadi and juxtaposes it against the material ways Turks of African descent have found to figure themselves within the public sphere. This juxtaposition demonstrates how Blackness and Black form are not perennial processes but rather constructed measures that come into relief.

Co-Option and Erasure: Mizrahi Culture in Israel

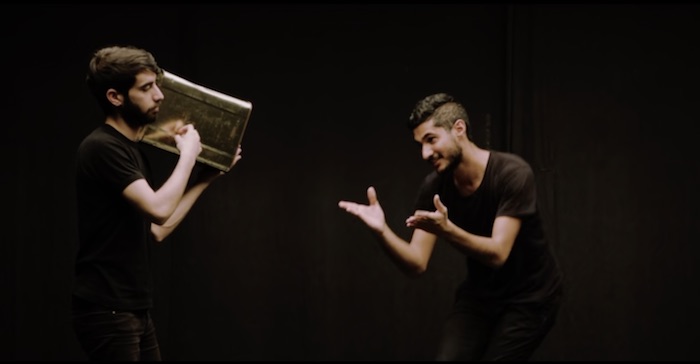

Much of the rhetoric around racism and racialized discrimination in Israel centers on Israeli Jewish treatment of Palestinians. However, an examination of the experience of Mizrahi Jews can also be instructive as to the ways that racism and white supremacy function within Israel—through a privileging of Ashkenazi Jews, whose experiences are used to define the contemporary Israeli Jewish experience. For example, Israeli Jewish artist of Yemeni descent Leor Grady’s work addresses the marginalization, erasure, and exile of Yemeni Mizrahi Jews in Israel. In his video work Eye and Heart, Grady highlights how, in its absorption into Israeli folk dance, traditional Yemeni dance has been uprooted from its site of origination and “whitewashed.” Through a discussion of this work and others alongside which it was shown in the exhibition Natural Worker, I argue that Grady’s articulation of the co-option of Yemeni culture by the dominant Ashkenazi (white) Israeli mainstream demonstrates how racialization plays out in the cultural realm of Israel. This method of privileging whiteness can be seen in the Israeli co-option of other Mizrahi and Palestinian cultural elements, such as couscous, hummus, and Arabic words such as “yalla.” This examination of Grady’s work allows for an understanding of how this privileging of whiteness functions within the Jewish Israeli context.

Thaumaturgic, Cartoon Blackface

This essay explores how a particular medium—the comic—exposes the limitations of conventional narratives about sīyāh bāzī (Persian blackface) and hājī fīrūz (a famous blackface figure). Many commentators disavow the racial connotations of sīyāh bāzī and hājī fīrūz, concocting pseudo-historical genealogies that link the improvisatory tradition and figure to pre-Islamic practices; commentators thus repress the tradition’s obvious resonances with the history of African enslavement in Iran. Through a close reading of a comic strip from a 1960s Persian periodical, I argue that historicism is an inadequate framework for adjudicating sīyāh bāzī’s racial or “nonracial” character. Instead, I suggest that cartoon Blackness is always already racial, since the comic form depends upon a process of simplification that is at the heart of racialization.

“Incommensurate Ontologies”? Anti-Black Racism and the Question of Islam in French Algeria

In recent years, scholars and activists in France and the United States have questioned whether discrimination against Muslims constitutes a form of racism. In France, some on the left have claimed that religion is a category of belief and therefore should remain separate from discrimination based on skin color or other physical characteristics. In the United States, Afropessimist approaches insist on the specificity of anti-Black racism, rooted in the historical difference between the native and slave. This article, by contrast, argues that race and religion should be studied relationally and highlights how being Muslim exceeded the frame of personal conviction in colonial Algeria, where religious identity was the basis of a political and economic project that were constructed in their wake. The works of Frantz Fanon are particularly instructive in this regard, as he insisted on viewing Blackness as fundamentally relational and also drew on his analysis of anti-Black racism in mainland France to understand the dynamics of settler colonialism in Algeria. The porous line between religious and racial categories also sheds light on discussions of sectarianism in the Middle East more broadly, as colonial regimes irrevocably shaped the contours of the nation-state that were constructed in their wake. Postcolonial sectarianism inherited the intimate relationship between race and religion constructed by empire.

Black Skin, White Cameras: African Asylum-Seekers in Israeli Documentary Film

The recent arrival in Israel of thousands of refugees from countries like Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Sudan has triggered a spate of hate crimes and mob violence. Asked about these asylum seekers in 2012, Likud-party member Miri Regev called them a “cancer.” For this comment, she later apologized—not to the African asylum-seekers but to Israeli cancer survivors, and she expressed regret for comparing them to Africans. Around that same time, Interior Minister Eli Yishai of the Shas Party told a reporter that “this country belongs to us, to the white man.” Continuing on, he stated that he would use “all the tools [necessary] to expel the foreigners, until not one infiltrator remains.” While the racial dynamics of Israel have been thoroughly examined with respect to both intra-Jewish tensions (Ashkenazi supremacy) and the Palestinian issue (white settler-colonialism), in this essay, I want to theorize Israeli whiteness with respect to the African refugees. Specifically, I will examine two recent Israeli documentaries dealing with African refugees—Hotline (dir. Silvina Landsmann, 2015) and Between Fences (dir. Avi Mograbi, 2016). Both openly demonstrate solidarity with the African asylum-seekers, but they do so in different ways, and if the former film leaves the racial hierarchies of Zionism intact, the latter works to shatter them.

What is Whiteness in North Africa?

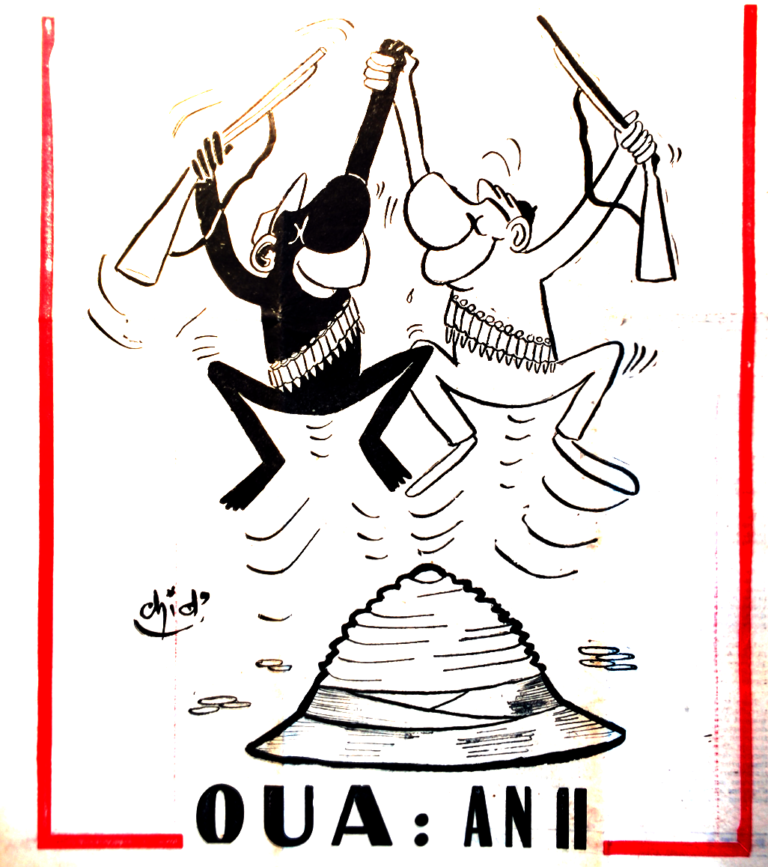

This entry sketches a matrix for conceptualizing race in/ and North Africa that takes Arabness, indigeneity, Islam, the Sahara, and slavery as orienting keywords. It suggests an approach to a geopolitically-grounded whiteness as social currency and aspiration that is both based in specific regional economic history and also reaches outward toward globally-circulating formations of racial hierarchy. Acknowledging the distinct legal, colonial, and state histories under and through which racialization has proceeded in North and Saharan Africa since the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, this entry aims to draw out the ethical imaginaries through which bodies have been marked and categorized in this region. These ethical imaginaries have operated through their attendant languages, memories, and performances to enable racisms and colorisms with violent and enduring material consequences. Under the headings “Racialized Enslavement,” “Whiteness and Arabness,” “Race and the Sahara,” and “Race in North African Popular Culture,” I offer brief introductions to these discursive formations, histories, and conceptual intersections and offer suggested readings for each.

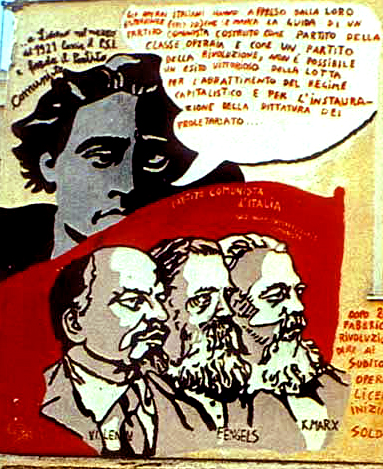

1986—The Marxist Disciplining of the Cultural Studies Project

Since its infancy, the pluralistic tendencies of the cultural studies project denied methodological and procedural consistency and resisted any disciplining of cultural studies as an attempt at authoritarian policing. Over the course of the 1980s, cultural studies continued to spread beyond the United Kingdom to Australia and the United States, initially, and the rest of the world soon thereafter. Movements towards the bridging of the longstanding divisions between fact and interpretation—between the social sciences and the humanities—under the sign of a principled approach to cultural democracy saw the Althusserian Marxism characteristic of earlier cultural studies scholarship expanded by way of a critical re/engagement of the works of Gramsci. This period of ideological critique allowed for a bold intellectual, political commitment to the re/conceptualization of culture as a site of class struggle, hegemonic formation, and structural signification. Particularly, the year 1986 saw major strides in this direction with the publication of monumental manuscripts by Stuart Hall, Ernesto Laclau, and Chantal Mouffe.

Review of Bans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary: Understanding U.S. Immigration for the Twenty-First Century by A. Naomi Paik (University of California Press)

A. Naomi Paik’s Bans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary responds to a trio of executive orders on immigration policy issued in the early days of Donald Trump’s presidency. Those orders sought to make good on campaign promises to further restrict immigration by banning citizens from Muslim-majority countries, allocating funds to expand a border wall between the US and Mexico, and ramping up home and workplace deportation raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Paik delineates how these legal barriers came to be by locating them in relation to the nation’s formative immigration policies, backlash to the liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s, and the global repercussions of neoliberalism. Highlighting the work of Indigenous activists, Paik eventually calls not only for the dramatic restructuring of the nation’s immigration system but also for the creation of a more just society based on relationships that reject the politics of inclusion and exclusion.

Review of The University and Social Justice: Struggles across the Globe edited by Aziz Choudry and Salim Vally (Pluto Press / Between the Lines)

In this edited collection, Aziz Choudry and Salim Vally present reflections and analyses from scholar-activists in education studies, anthropology, literature, and cultural studies describing university-based and affiliated social movements. Through thirteen essays covering case studies in twelve countries, the anthology offers a broad review of student organizing against neoliberalization and more specifically, the privatization of higher education; intersectional and coalitional strategies imagined through these struggles; and alternative modes of knowledge production pre-figured in their organizing. Geographic and disciplinary breadth make the anthology a welcome addition to the growing corpus of (transnational) critical university studies.

Review of Art as Revolt: Thinking Politics Through Immanent Aesthetics, edited by David Fancy and Hans Skott-Myhre (McGill-Queen’s University Press)

The entanglements of “the aesthetic” and the political-economic have long been addressed in the areas of philosophy, cultural studies, and media theory. In this edited volume, David Fancy and Hans Skott-Myhre have assembled a collection of essays aimed at examining a range of aesthetic approaches to political projects untethered to “capitalist assumptions,” while looking toward the possibilities of “post-capitalist futures.” Through their respective contributions, the authors offer their readers ways to envision the potential for running lines of flight away from capital’s apparatuses of capture by engaging in creative practice.

Review of Culture and Tactics: Gramsci, Race, and the Politics of Practice by Robert F. Carley (State University of New York Press)

In Culture and Tactics: Gramsci, Race, and the Politics of Practice, Robert Carley brings a wide array of theoretical and empirical study to make the claim that Antonio Gramsci was a critical race theorist, that Stuart Hall’s important theoretical contributions like articulation are necessarily Marxist to bring structure and agency, long “opposite ends” of the sociological spectrum together in dialectical terms, for one to build a foundation for his original theories. He does so too when uses Gramsci’s and his own work on race and ethnicity in early twentieth century Italy to bring light to the ideological aspects of today’s social movements of race and class. In doing so through his various methodologies, he introduces his theory of ideological contention to explain who social movement organizations organize their tactics and how those tactics influence how groups organize, or practice ideology. His theory of aporetic governmentality, built of the foundations of Michael Foucault and Eduardo Bonilla Silva elucidate the process of institutional racism and how is manifests at the cultural and individual level, bringing a much needed Marxist lens to the issues of race, class, and social movement theory. Carley succeeds in achieving an interdisciplinary work that encompasses the areas of research needed for scholarly work that not only analyze, but create innovate theories that add to the multiple fields of research.

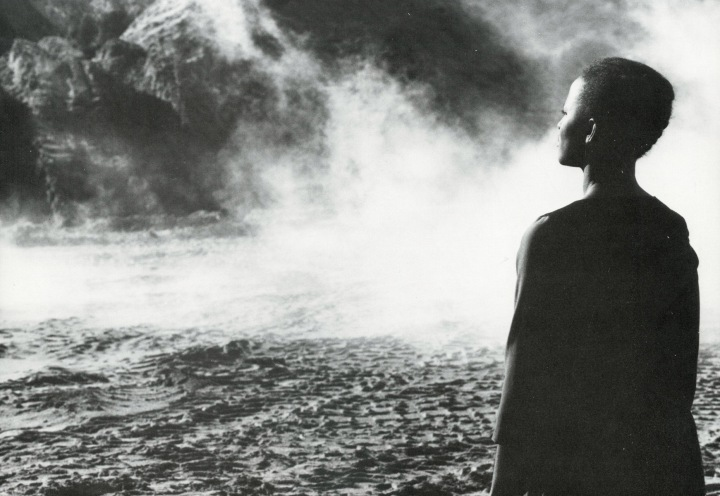

Political Blackness, British Cinema, and the Queer Politics of Memory

This essay queries “political Blackness” as a coalitional antiracist politics in England in the 1970s and 1980s. Contemporary debates on the relevance of political Blackness in contemporary British race politics often forget significant critiques of the concept articulated by feminist and queer scholars, activists and cultural producers. Through close readings of Isaac Julien and Maureen Blackwood’s The Passion of Remembrance and Hanif Kureishi’s Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, this essay examines cinematic engagements with political Blackness by foregrounding the gender and sexual fault lines through which queers and feminists articulated relational solidarities attentive to difference.

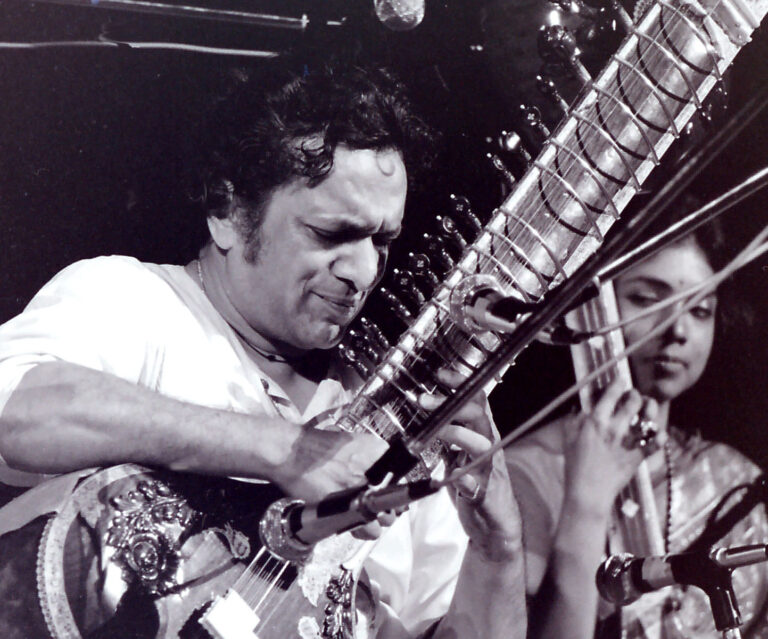

Sounds from Nowhere: Reading Around Raga-Jazz Style

When Pandit Ravi Shankar began performing for Western audiences in the 1960s, his collaborative instinct for the meeting of Hindustani music and jazz was challenged by what he described as “shrieking, shouting, smoking, masturbating, and copulating” audiences of “strange young weirdos,” according to Mick Brown writing for The Telegraph. We can only imagine the debates of high and low art which were fought between Shankar and George Harrison, Bud Shank, or even Tony Scott, who were few of his many collaborators from the West. Caught between its original referent and its appeal to learned style, jazz (with its roots in African-American history) is placed at the center of debates about authenticity, gatekeeping, and located-ness. Once something like “world music,” composed through collaboration, fusion, and re-sampling, enters a space not used to any of the styles mixed into this world of music, it creates unique soundscapes. Ethnomusicologist Martin Stokes, writing “On Musical Cosmopolitanism,” looks at the course of sounds through the world to think of music “as a process in the making of ‘worlds,’ rather than a passive reaction to global ‘systems'” (6). The world created is never an unproblematically imported ambience. A jazz club anywhere in the world does not always correspond to Dixieland, or Chicago, or New York, nor does it reveal the influence of Black labor-songs, vaudeville, or ragtime. This is where an album like Indian composer duo Shankar-Jaikishan’s Raga-Jazz Style (1968) becomes interesting, compressing 11 ragas from Hindustani music into curt pieces corresponding to different, morphed forms of jazz. By looking at the history of the circulation of interfused styles of jazz in America, Goa, Bombay, and mainstream Hindi cinema, this paper examines the material conditions of creativity, and attempts to inscribe this global creative collaboration of forms into a connected history of jazz and Hindustani music.